5

Building Local and National Capacities for Outbreak Preparedness

After the opening presentations, the workshop’s first session covered major lessons learned from a century of major outbreaks and pandemics, examining the advances that have been made and lessons that still need to be applied from the local to national to global levels. Specifically, session 1 part A focused on the panelists’ experiences with strengthening local- and national-level capacities after different types of outbreaks in diverse country contexts. Moderator Suerie Moon, director of research at the Global Health Centre, The Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, emphasized that community- and national-level preparedness serve as the first line of defense against any infectious disease outbreak, a concept that was codified in the 2005 revision of the International Health Regulations (IHR) in the aftermath of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak. National-level preparedness is important not only for particular countries, she said, but also for the global community at large; building an adequate minimum level of capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to public health risks has become an international obligation. After the Ebola crisis of 2014, efforts to strengthen accountability among countries with respect to national-level preparedness gathered momentum through the World Health Organization (WHO) Joint External Evaluation (JEE) process (WHO, 2016a). She explained that this voluntary, collaborative peer-review process that assesses national capacities to prevent, detect, and respond to public health risks has contributed to strengthening political will and encouraging investment in national preparedness capacities. Moon called this one of the most significant reforms that occurred in the wake of the Ebola epidemic, but noted that sustaining

the necessary funding, political attention, and leadership for investing in those capacities remains a challenge and looked forward to the panelists’ perspectives on this matter.

The first panelist, Abdullah Assiri, assistant deputy for preventive health at the Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia, discussed lessons learned from the emergence of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in Saudi Arabia in 2012 and changes that have been made in the country’s public health systems in the past few years. Mosoka Fallah, deputy director general for technical services of the National Public Health Institute, Liberia, described the lessons learned from the Ebola outbreak of 2014 and progress made in developing core capacities to respond to future outbreaks in Liberia. Gabriel Leung, dean of medicine at The University of Hong Kong, reflected on how Hong Kong’s public health capacity-building efforts have strengthened since the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong in 2003. Finally, Amanda McClelland, senior vice president of Prevent Epidemics at Resolve to Save Lives, offered insight about her experiences working on the frontlines with international organizations and local communities during outbreaks and about her perspective on how to build local and national preparedness capacities.

LESSONS FROM THE MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME OUTBREAK IN SAUDI ARABIA

Abdullah Assiri, assistant deputy for preventive health at the Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia, described the MERS outbreak in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. MERS, a viral respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus (CoV), was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012, and by the end of 2018, more than 2,200 laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS were reported, around 85 percent of the cases issued from Saudi Arabia.1 MERS has not been eliminated, but infection prevention practices have brought the outbreak under control, and currently the case fatality rate is stable at around 35 percent.

Although the toll of MERS has been difficult for Saudi Arabia, Assiri said the outbreak has positively transformed the country’s public health system. A public health emergency operations center initially established to respond to MERS-CoV has since expanded its function and scope to include all infectious disease hazards, with 20 regional incident command systems across the country, reported Assiri. In addition, the laboratory system has been upgraded to improve detection of MERS, and a nationwide system to transport biological samples is now in place. Most MERS outbreaks in Saudi Arabia were associated with health care facilities, he noted. Although

___________________

1 WHO’s current MERS surveillance information is available at https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en (accessed January 29, 2019).

human-to-human transmission of MERS is typically limited, it is more common in health facilities because patients with MERS-CoV are typically admitted when they are at the peak of their infections and are more likely to transmit the disease to other people in the facilities (WHO, 2016b). In response, the government has invested in upgrading the infection control infrastructure. Assiri reported that tens of thousands of health care workers have been retrained on basic infection control skills, including respiratory protection and environmental contamination procedures. Health care facilities are externally audited four times per year to ensure compliance with basic infection control standards, he added.

Leadership in Saudi Arabia is committed to advancing emergency preparedness in its public health agenda, said Assiri. High-ranking officials have been repositioned to better respond to MERS, and on multiple occasions, leaders have participated in public health emergency drills related to antimicrobial resistance and respiratory outbreaks. To address MERS, he explained that the government has also created a high-level, multidisciplinary One Health team comprising experts from three ministries directly related to zoonotic diseases.

While the scientific community in Saudi Arabia has learned from the experiences of MERS-CoV and has moved into a stronger position to prepare for, detect, and respond to infectious disease threats, they have continued to struggle with two country-specific challenges related to infectious disease transmission and outbreaks. One challenge is the risk of transmission in mass gatherings (see Box 5-1), and the other is the prevalence of coronaviruses among camels in the country. Assiri reported that Saudi Arabia has more than 2 million camels, but many are hyperinfected with MERS. The animals do not appear to have long-lasting immunity to coronaviruses and therefore can become reinfected multiple times. Camel-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV is a major concern (Alshukairi et al., 2018). Assiri said health professionals are exploring camel vaccination and are conducting trials of potential therapeutic options, but this is challenging because of the complexity of the camel immune system and the technical difficulties related to dealing with such large animals.

LESSONS FROM THE EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE EPIDEMIC IN LIBERIA

Mosoka Fallah, deputy director general for technical services of the National Public Health Institute, Liberia, reflected on his country’s experience during and after the Ebola outbreak of 2014–2016. By September 2014, Liberia accounted for more than half of Ebola cases in West Africa (CDC, 2014). Fallah described Liberia as a prime example of a country with a weak health system that was unprepared to deal with a crisis. When

the Ebola outbreak struck, the country’s poor health infrastructure and limited laboratory capacity delayed detection of the disease and precipitated its transmission. The nearest laboratory with diagnostic capabilities was in Guinea, requiring staff to make a 2-week journey to transport samples back and forth. Because Liberia lacked trained epidemiologists and surveillance officers at the time, the spread of the outbreak from rural areas into populous, urban centers was unmitigated, and transmission escalated quickly. High rates of nosocomial infection also accelerated transmission of the disease. A large proportion of health care providers in the country became infected, and many became superspreaders (Lau et al., 2017).

According to Fallah, Liberia took bold and innovative steps to respond to the outbreak that helped Liberia become the first country in the region to be declared Ebola free. For example, a lack of national protocol regarding risk communications led to initial mistakes in public messaging, but these were modified to provide a positive effect. At the beginning of the outbreak, the public was told that they would die if they contracted Ebola, which discouraged patients from seeking treatment and facilitated disease transmission. When public messaging changed to encourage patients to seek treatment early to increase their chances of survival—coupled with positive stories of people who survived the disease—people were more willing to seek care in treatment units (Schwerdtle et al., 2017). Liberia also

invested in creating comfortable care environments for people who were being treated for Ebola. In addition, a point-of-care diagnosis innovation enabled health workers to draw blood in the field, which helped end the outbreak in Liberia; it reduced the turnaround time for diagnostic testing to 2 hours versus the 6 hours required for polymerase chain reaction testing (Nouvellet et al., 2015).

Liberia’s progress around developing core capacities to respond to future outbreaks is the silver lining of the country’s Ebola outbreak, said Fallah. He described some of the lessons learned during the Ebola outbreak, and practices that have since been introduced. To alleviate the burden on the Ministry of Health, Liberia created an independent National Public Health Institute in 2017 to carry out surveillance and develop laboratory capacities. The institute now has the ability to test for seven pathogens and has responded to 39 outbreaks thus far. Its response turnaround times to non-Ebola outbreaks are of less than 1 week (NPHIL, 2017). Liberia had two resurgences of Ebola in 2017, both of which were contained within 3 weeks and provided an opportunity to carry out trials of new vaccination strategies (NIAID, 2017). Because of improved early detection capabilities, survival rates for Ebola have increased dramatically, and Liberia is now able to deploy the ZMapp2 vaccine as a complementary countermeasure (Nyenswah et al., 2016). Fallah added that the development of sensitive surveillance systems and robust laboratory capacity have enabled the country to quickly and effectively contain recent cases and outbreaks of yellow fever, Lassa fever, and monkeypox. Strategies to further institutionalize preparedness include testing the system at least once per year and convening weekly meetings with partners across relevant sectors from logistics to coordination. Liberia is now ready to shift immediately from preparedness to incident management when an outbreak occurs, Fallah said. However, the country’s reliance on foreign donors for logistics and reagents is a challenge that remains to be addressed.

LESSONS FROM THE SEVERE ACUTE RESPIRATORY SYNDROME OUTBREAK IN HONG KONG

Gabriel Leung, dean of medicine at The University of Hong Kong, presented on the lessons drawn from the 2003 outbreak of SARS in Hong Kong. Like other affected areas—including Canada, Mainland China, Singapore, and Taiwan—Hong Kong did not have the necessary capacities

___________________

2 ZMapp is a vaccine made of three different monoclonal antibodies, designed to prevent the progression of Ebola virus disease in the body by targeting the main surface protein of the Ebola virus (NIAID, 2016).

in place to respond to the outbreak.3 In the aftermath of SARS, Hong Kong established a new national health agency, the Center for Health Protection, and created new regional- and national-level liaisons with Mainland China to facilitate communication and coordination among their regulatory sectors for health, food, and commerce. Subsequent changes have included supply-chain management through farm registration, pre-import testing, and quota controls for farm animals that are integral to the influenza transmission cycle, such as poultry and swine.

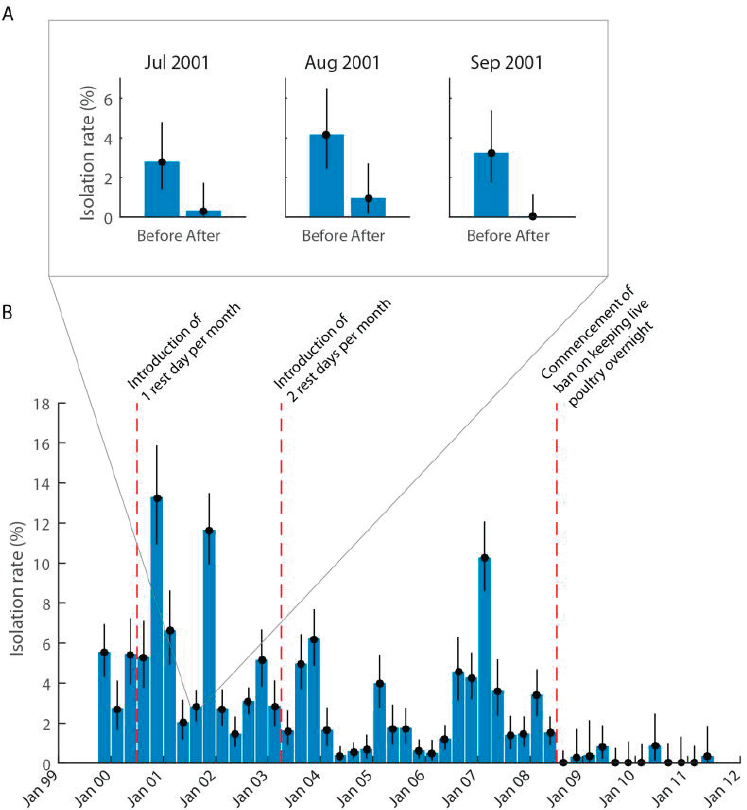

Leung described some of the capacity-building efforts that have been implemented in Hong Kong since the 2003 SARS outbreak in order to reduce infectious disease transmission, improve public messaging, strengthen early detection, and build laboratory capacity. A set of progressive interventions was implemented in local farm wholesale and retail poultry markets to reduce influenza transmission. The first intervention introduced a rest day once per month to allow retail markets to be cleaned, but this was not sufficiently effective, so the rest-day frequency increased to every 2 weeks. This generally reduced transmission to acceptable levels, but outbreaks were still occurring. However, the transmission rate dropped to almost zero when Hong Kong introduced a policy that prohibited live poultry from being kept in markets overnight (Peiris et al., 2016). Figure 5-1 illustrates the impact of the progressive introduction of these measures targeting poultry markets on the tracer influenza virus isolation rate. Other efforts in Hong Kong have included proactive health communication regarding messaging, behavior surveillance, and engagement with the public. Since public hospitals account for more than 90 percent of all admissions in Hong Kong, seasonal influenza surges are addressed through a universal policy of screening all febrile respiratory admissions in public hospitals. In terms of laboratory capacity building, Leung said that Hong Kong has a high density of biological safety level-three laboratories, as well as a WHO Collaborating Center and two WHO-designated H5 reference laboratories with a mandate to provide WHO with data and risk assessments on H5 and other animal influenza viruses (HKU, 2019).

Leung then described Hong Kong’s response to two infectious disease events that have occurred since the 2003 SARS outbreak. During the pandemic H1N1 outbreak in 2009, an entire hotel was quarantined for 1 week, schools were closed early, and a proactive public communication strategy was tested; these efforts helped to delay local transmission by 40 days (Wu et al., 2010). Subsequent evaluation has shown that school closure reduced transmissibility by 12–25 percent (Jackson et al., 2014).

___________________

3 Leung noted that all of those affected countries subsequently replaced their top echelons of health officials, and they either established post hoc national health agencies or transformed their existing national health agencies.

SOURCES: Leung presentation, November 27, 2018; reprinted from The Lancet, Vol. 16, Malik Perkis et al., Interventions to reduce zoonotic and pandemic risks from avian influenza in Asia, 252–258, (2016), with permission from Elsevier.

However, he noted that only during the H1N1 pandemic did school closures substantially reduce transmission. When schools were closed on two other occasions in 2008 and 2018, this intervention was associated with only modest reductions in transmission of 4 percent or less (Cowling et al., 2008; Ali et al., 2018). Vaccination efforts were carried out during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic response, he added, but it was “too little too late,” and

most of the vaccines the government purchased were not used. Although the 2013 H7N9 outbreak did not reach Hong Kong, Leung and his colleagues contributed to the regional outbreak response in and around Shanghai. Leung and his colleagues helped to report on the first series of clinical cases, to determine the pathogenesis of the H7 subtype, to characterize the epidemiology of H7, and to examine the potential impact of closing poultry markets (Chen et al., 2013; Cowling et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2013, 2014). Reflecting on the progress made in Hong Kong over the past 15 years in terms of building the capacity to respond to infectious disease outbreaks, Leung believed it could be achieved in other countries and could lead to improved pandemic preparedness on a global level.

LESSONS FROM WORKING IN THE FRONTLINES WITH LOCAL COMMUNITIES AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

Amanda McClelland, senior vice president of Prevent Epidemics at Resolve to Save Lives, reflected on her global experience working at the interface of communities and health systems. After years focused on engaging community and health care workers, she has come to realize that capacity building and shifting the course of an epidemic ultimately sits with politicians. McClelland said national governments and public health professionals tend to wait until a crisis occurs to build capacity, creating a cycle of panic and neglect in which public health workers are sidelined during periods when the necessary capacity building could be achieved. Shifting the conversation to engage politicians and communities would help break this cycle, she suggested (see Chapter 8 for more on breaking this cycle of panic and neglect). However, the preparedness enterprise is complex and difficult to explain to politicians and decision makers. For example, the JEE contains 19 technical areas and 54 indicators; national preparedness action plans may have more than 400 priority actions for the first year alone.4 A program manager in a low-resource country may be tasked with coordinating six ministries over 200 or 300 priority preparedness actions. McClelland noted that countries furthest away from a sufficient level of preparedness are even less likely to have political buy-in and financial resources needed to build and support complex systems that are IHR-ready.

McClelland mentioned that Resolve to Save Lives would like to see a reduction of the number of requisite capacities and to prioritize core activities for preparedness. Ideally, this process would engage with communities in under-resourced countries to help them detect, prevent, and respond to outbreaks. For example, Resolve to Save Lives has been working to reduce

___________________

4 For more information on the JEE components, see https://www.who.int/ihr/procedures/joint-external-evaluations/en (accessed February 8, 2019).

the 400 priority actions to an essential set of 50 actions that are focused on seven of the 19 technical areas within the JEE (Vital Strategies, 2018).5 The main focus has been on building response, surveillance, laboratory, and health workforce capacities, then using legal and financial preparedness and risk communications to lever those capacities. McClelland said the legal and finance indicators within the JEE have posed barriers to moving forward because if countries do not have the mandate to declare emergencies, it is difficult to generate financing and gain political buy-in for preparedness. She added that improved capacities can potentially be problematic to explain to politicians. For example, if improved detection increases the frequency with which high-profile infectious disease outbreaks are declared, then political leadership may question the effectiveness of preparedness efforts. Capacities to report evidence and support politicians and policy advisors should be built in conjunction with the capacity to detect outbreaks, she suggested.

McClelland remarked that some capacities related to prevention, early detection, and response components are missing or not prominent enough in the JEE and IHR frameworks, even though these frameworks are helpful tools. For instance, the JEE is designed to ensure that countries can be IHRcompliant, but IHR compliance is not necessarily analogous to epidemic preparedness. With respect to the JEE, she noted that infection prevention and control components are not prominent, nor are capacities for frontline health care workers to detect, respond, and engage with communities during an outbreak. The Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is an example of the importance of empowering frontline health workers to deliver epidemic care, she highlighted, especially in conflict or hard-to-reach areas that should be accessible without depending on a regional or an international response. Furthermore, the JEE does not emphasize the role of civil society or how governments can engage with non-traditional partners. She suggested that these core capacities should be built by working within the JEE structure while still bearing in mind the lessons learned from past responses.

DISCUSSION

Remarking on the presentations, Suerie Moon, director of research at the Global Health Centre, The Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, observed that the improvements in capacity building and knowledge gathering described by panel participants are grounds for optimism, but a number of challenges persist. Realistically, it is unlikely

___________________

5 The Resolve to Save Lives platform with resources and JEE country data can be found at https://www.preventpandemics.org (accessed February 26, 2019).

that outbreak preparedness will remain high on the political agenda, so any short window of opportunity should be exploited in order to institutionalize change (e.g., new funding commitments, procedures such as the JEE, or national public health agencies). Although such windows of opportunity usually occur after a crisis, she was hopeful that a recent reform aimed at strengthening international accountability through the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board, organized by WHO and the World Bank, would help to institutionalize attention on existing weaknesses (see Chapter 2 for more on this board). Moon also observed that national capacity building warrants improved international support. For instance, accountability for preparedness varies widely across countries, with fewer than half of member states having participated in the JEE process. She highlighted the risk posed by harmful competition among different health agendas. For investments in preparedness to be politically sustainable, they should deliver tangible benefits for populations in the form of better health care today, not only during a crisis. Resource-constrained communities should not have to choose between day-to-day health care delivery and preparedness, she said, so investments should serve to strengthen both capacities.

Current National Challenges to Manage a Potential Major Disease Outbreak

Moon asked Fallah, Assiri, and Leung about the current state of preparedness at the national level, including challenges they continue to face. Specifically, she asked Fallah how national public health institutes in resource-constrained settings might encourage investment in preparedness, despite competing priorities related to the day-to-day provision of health care services. Fallah explained that Liberia’s National Public Health Institute was created when the Ebola crisis demonstrated that public health threats could cripple the entire health system. The institute was developed to focus specifically on developing an early warning and surveillance system, and its initially committed budget has already faced potential cuts. Liberia’s preparedness is fragile, he said, because the system is heavily dependent on donor funding, and any funding change can severely hamper its preparedness. Long-term funding mechanisms are needed to improve stability, he said. Liberia’s preparedness is also skewed toward public health response to infectious disease outbreaks while multi-hazard response preparedness remains weak. Although diagnostic capacity has improved, he noted response is generally initiated only after multiple patients have died, rather than detecting patients at an early stage. Fallah agreed with Moon’s earlier comment that a balance needs to be struck between investment in preparedness and investment in day-to-day health systems that are critical for the population’s health and for reducing the transmission of infectious diseases.

Given the measures in place to reduce the level of infections from MERS, Moon asked Assiri about the extent to which MERS has become normalized as a semi-permanent fixture in the health landscape of Saudi Arabia. Assiri said that MERS continues to be a public health threat because of the continuous spillover of the virus from camels to humans. Although Saudi Arabia’s investment in improved infection control within health care facilities has strengthened its preparedness to control future outbreaks, improvements in preparedness have not yet expanded to other infectious diseases or hazards, because efforts have focused primarily on MERS. For example, Saudi Arabia has largely reduced the risk of animal-to-human transmission of MERS by enacting laws to prevent the importation of camels into the Hajj area; as a result, he said influenza transmission is a greater concern during Hajj than MERS-CoV.

Moon asked about Hong Kong’s overall state of preparedness for a major infectious disease outbreak. Leung responded that Hong Kong is not actually as prepared for a large-scale event as it would seem. A country is only as safe and secure as the weakest link in its entire area, he noted, and Hong Kong’s population represents just 10 percent of the roughly 80 million people who live in the network of interconnected cities and villages in the Pearl River Delta (Cooper, 2014). Furthermore, Hong Kong imports about 95 percent of its food, which compromises its security from a One Health perspective (USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, 2017). In addition to directly transmissible respiratory pathogens, vector-borne diseases are also a major concern in the region.

Engaging and Motivating Communities and Politicians for Preparedness

Moving on to the topic of motivating communities and decision makers for preparedness, Moon asked McClelland about challenges related to engaging, mobilizing, and communicating with communities in settings with weak social cohesion, such as conflict or post-conflict areas. McClelland replied that communities with weak social cohesion tend to unify around a common cause when a natural disaster occurs, but such collaboration does not often occur in an epidemic response. In fact, existing social cohesion can easily be compromised by mistrust and poor messaging during a major epidemic. She noted that the social science component of epidemic response—which is often relegated to risk communications—should be centralized in emergency operations as part of incident management and should be leveraged in every pillar of a response. Because of the constant flux in social cohesion and the relevance of social science to both pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions (e.g., vaccination, school closures, and handwashing campaigns), she suggested

that social science should be integrated into behavioral measures and used to monitor social cohesion in relation to the dynamics of transmission.

Jonna Mazet, executive director of the One Health Institute and professor of epidemiology and disease ecology at the University of California, Davis, added that politicizing diseases can lead—and has led—to misinformation, divisiveness, and mistrust that negatively impact future interventions. She asked how the global health community could empower communities to embrace prevention and preparedness while also limiting that political posturing. Following up, Keiji Fukuda, director and clinical professor, School of Public Health, The University of Hong Kong, asked panelists about the factors that can drive decision making and progress in capacity building for preparedness, without relying on a crisis as the catalyst.

Leung said it is easier to persuade countries to invest in preparedness if they have experienced multiple major outbreaks, particularly those with severe economic and political impacts. For countries that have not experienced such catastrophes, he said, it could be helpful to highlight the experiences of countries that have, in order to motivate precautionary investment in preparedness. Local governments can take action through three levels of engagement, Leung explained. One level is to communicate through media, especially social media, to directly and proactively engage with the population so that they will lobby politicians about the importance of pandemic preparedness. The second level is to forge relationships and exchange information with the global health community at the technocratic level. These crucial relationships may lead to building capacity during interim periods or may emerge as a result of simultaneously having experienced a major epidemic. The third level is to use supranational or multilateral agencies to promote the importance of preparedness in international fora. Although this approach may not result in much change on the ground or at the technocratic level, he said, the political significance of raising the issue is a kernel that can be followed up.

Assiri commented that advocacy for preparedness requires keeping decision makers on their toes—for example, seven ministers were replaced in Saudi Arabia due to the MERS outbreak. This directly led to a sevenfold increase in the public health budget between 2012 and 2018, he stated, and it also changed the way that other diseases are addressed. He suggested that momentum can be maintained by media engagement and by keeping public health at the top of the government’s agenda. Assiri added that the JEE process has also been helpful in fostering political leadership’s interest in public health. McClelland noted that the JEE was not designed to pit countries against each other, but competitiveness in preparedness has emerged as a motivating factor that will help to compare progress among countries as the JEE process enters its second round. Fallah remarked

that politicians’ tendencies to focus on the economic impact of diseases could be leveraged to encourage preparedness. However, now that more sensitive surveillance systems are enabling more diseases to be detected, some countries have become concerned about sharing outbreak-related information that may have economic and security-related implications. This has posed a challenge to regional efforts to build capacity in Africa, he said, and there is a delicate balance to strike between countries’ rights to protect sensitive information and the global community’s need for information about outbreaks.

McClelland observed that the perception of risk—of an epidemic or of potential economic loss—is the biggest entry point for mobilizing governments and communities and for motivating change. Thus, as Leung indicated, it is difficult to mobilize effectively unless there has recently been a major risk, she said. At the community and government levels, people tend to focus on balancing risks and prioritizing behavior change. In terms of public health, it is difficult for a politician to prioritize investing in an emergency operations center that is activated only once per year over investing in maternal and child health; similarly, she added, it is easier to mobilize a community to demand better maternal and child health care than to demand better infectious disease outbreak preparedness. She underscored that motivating investment in preparedness needs to be country- and community-specific, and suggested taking a strategic view—country by country and community by community—to assess the risks, risk perceptions, and choices that communities and governments make to prioritize preparedness above other health risks or other economic or safety risks.

Finally, Dennis Carroll, director of the Global Health Security and Development Unit of the U.S. Agency for International Development, added that the private sector could be leveraged more effectively to boost preparedness efforts. He remarked that the SARS outbreak had a large impact on the global supply chain and that the Ebola outbreak motivated collaborative action from the extractive industry and agribusiness sector, which recognized the risk and self-mobilized to try to mitigate it. He suggested the power of the business sector could be harnessed in its own self-interest for risk mitigation, for example, through business continuity plans and the sector’s influence on politicians and communities.

This page intentionally left blank.