6

Demography of Aging and the Family

INTRODUCTION

Population aging is a marker of our success in both extending longevity and planning our reproduction. The demographic changes that result in the aging of the population also contribute to family change in aging societies. At the same time, changes in demographic behaviors, such as marriage and childbearing, have transformed the intergenerational structure of society. Each of these phenomena also has contributed to an increasing diversity of family forms, raising questions about societal and individual responsibility for well-being in old age. Countries vary in their approaches to social welfare, but even in the most generous ones, families remain the most tenacious and preferred sources of support when individuals need help. The role of the public-private divide in responding to the needs of aging populations has been as much at the center of demographic research on family change, living arrangements, and support as the changes in the family itself.

Demography also has contributed to methodological approaches that allow studies of families and intergenerational relations to be more complex and realistic. Demographers have developed and refined macrosimulation and microsimulation approaches to family change that enable the projection of distributions of family types for policy and planning purposes.

This chapter reviews the ways in which population aging has contributed to an increasingly complex set of family relationships in later life and

___________________

1 Johns Hopkins University.

the implications for intergenerational support, care-giving, and new family forms.

DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE AND FAMILY STRUCTURE

The process of population aging results from a confluence of trends, most notably declines in fertility and mortality and a shift in the timing of death to increasingly later ages. These trends have intersected with changes in the role of women, the decreasing size of family households, and the timing of family events to reshape families in later life.

Longevity

Population aging has been driven primarily by declines in fertility, but improvements in longevity since the latter part of the 20th century—especially survival at older ages—also have contributed to population aging. Increases in life expectancy allow for more years spent in family roles as a spouse, sibling, or parent but also for the possibility of occupying many family roles throughout one’s lifetime—either concurrently or in succession—through divorce, remarriage, migration, changing living arrangements, and the acquisition and loss of other family relationships. As Bengtson (2001) noted, the importance of intergenerational relationships rises as the number of surviving generations increases.

Wiemers and Bianchi (2015) used the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to show that almost two-thirds of American women in the Baby Boom cohort had at least one living parent when they were ages 45–64, substantially higher than women born during the 1920s and 1930s, about 38 percent of whom had a living parent at that age. Consistent with socioeconomic status (SES) differences in life expectancy, the likelihood of having a living parent is greater for those of higher social class. Henretta and colleagues (2002) analyzed Health and Retirement Study (HRS) data and found that the proportion of women ages 55–63 with a living parent was 5–7 percentage points higher among those with higher education, income, or occupations.

Improvements in old age survival also increase the likelihood of having a living spouse or ex-spouse. Joint survival of spouses has resulted both from the gains made by men in life expectancy in recent years and from enhanced survival among married individuals, especially married men (Rendall et al., 2011). These differentials may become exacerbated in future cohorts as they age, since newer marriages are becoming more educationally homogamous and marriages among those with higher education tend to be more stable (Schwartz and Mare, 2012; Cherlin, 2014). Siblings also are an important part of later-life family relationships, and most older per-

sons have at least one living sibling, many with more than one—a legacy of the large families of the past (Agree and Hughes, 2012).

Fertility

Fertility has historically been the most powerful demographic factor contributing to population aging, eclipsing both mortality and migration in its impact on the age structure. Fertility is an important component of age structure change because it can change more rapidly than mortality and have an immediate effect. The most well-known example of this is the post–World War II Baby Boom, which slowed the aging of the U.S. population for some decades, with median age dropping from 30.2 in 1950 to 28.1 by 1970 (Hobbs and Stoops, 2002). The Baby Boom resulted from traditional preferences for larger families promoted by post-war economic growth and also from earlier marriages and less childlessness.

However, as women’s roles evolved over the latter part of the last century, lower fertility intentions became more common and achievable, leading to declining family sizes. The mothers of the Baby Boom averaged 3.1 children ever born, and 36 percent had 4 or more children, whereas those born in the late 1960s averaged 1.9 children and only 11.6 percent had families of 4 or more. At the same time, a rising prevalence of childlessness in more recent cohorts increased the number of individuals reaching older ages with no children. Whereas only 10 percent of women born in the 1930s were childless at age 45, this statistic had risen to 17 percent for women born in the late 1960s (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017a).

Related trends in the timing of childbearing also took place over the past century. Two notable trends affecting kin availability at older ages are the decline in adolescent childbearing and the increasing age at first birth. Birth rates among those ages 15–19 rose steadily through the Baby Boom period from 54.1 per thousand in 1940 to 96.3 in 1957—the year with the peak volume of births (Lu et al., 2015). Since then, the rate has steadily declined, reaching an unprecedented low of 20.3 births per thousand teens in 2016 (Martin et al., 2017). The nature of teen births has changed as well. About 15 percent of teen births 80 years ago were premarital, compared with 75 percent of teen births today2 (Bachu, 1999; Martin et al., 2017).

Equally significantly, birth rates at older ages have been increasing, with a substantial proportion of women having first births at ages 30 and older. Most of today’s older women began childbearing by their early twenties, but since the mid-1970s the first-birth rate for older women has been rising.

___________________

2 The proportion that was either conceived or born premaritally rose from 30 to 89 percent over this time period, and the proportion of teen premarital conceptions that led to marital births declined.

Only 2.5 percent of those born in the 1930s had a first birth after 35, versus 9–10 percent of cohorts born from 1956 to the 1960s (Matthews and Hamilton, 2014). Future cohorts are likely to have even later reproductive histories; in 2016, the fertility rate for 30–34-year-old women was higher than that of 25–29-year-olds for the first time (102.7 versus 102.1) and 30 percent of all first births were to women over 30 (Martin et al., 2017).

Increases in childlessness and later, shorter childbearing decreases the types and duration of family roles experienced by many adults and increases the average number of years separating generations. However, period trends in later childbearing intersect with the intergenerational transmission of fertility within families and the correlation between mothers and daughters in the timing of first birth (Kim, 2014). In those families where early parenthood is normative, the years between generations are small and family members occupy more roles for more years. Between 1998 and 2010, 40 percent of adults between ages 50 and 59 were part of families with four living generations. Even 11 percent of men and 5 percent of women in their seventies had a parent, children, and grandchildren alive (Margolis and Wright, 2017).

Nuptiality

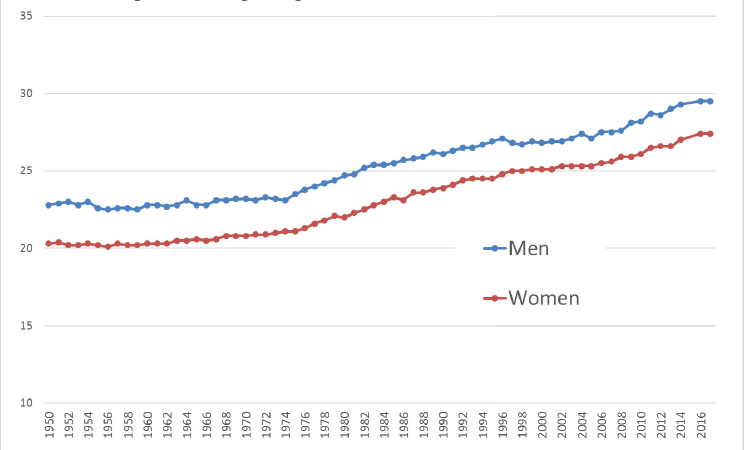

The changes in fertility described above were a product of dramatic changes in the second half of the 20th century in women’s roles, especially greater access to the labor force and to higher education. Employment and marriage were no longer seen as tradeoffs for women. All women, including married women and mothers, began working for pay in greater numbers; investments in women’s education pushed marriage and childbearing to later ages, especially for those with a college education; and the stigma of nonmarital childbearing declined. Figure 6-1 shows the rise in median age at first marriage in the United States from about 20 for women and 22 for men in the 1960s to 27 for women and 30 for men in 2017. Older Americans today are just beginning to show evidence of these changes. The oldest old, born during the 1930s, married early (more than three-quarters of women married by age 25), compared to only one-half of the cohort born after 1956 (Kreider and Ellis, 2011).

Transformations in norms about sexuality and family life accompanied changes in women’s roles. As more effective birth control became available, gender roles more fluid, and family responsibilities more volitional, alternatives to lifelong marriage commitments such as divorce, remarriage, and cohabitation became acceptable. Divorce rates began to rise, reaching a peak around 1980, and cohabitation in place of marriage became more common, first for those formerly married and then as a prelude or a substitute among those who had not yet married (Cherlin, 2010). Divorce rates have aged with the population; the divorce rate among adults ages 50 and

SOURCE: Data from U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, March and Annual Social and Economic Supplements.

older doubled between 1990 and 2010 (Brown and Lin, 2012). Despite these trends, marriage remains popular among both men and women. Almost all older adults married at least once, and remarriage rates after divorce or widowhood are high (Agree and Hughes, 2012).

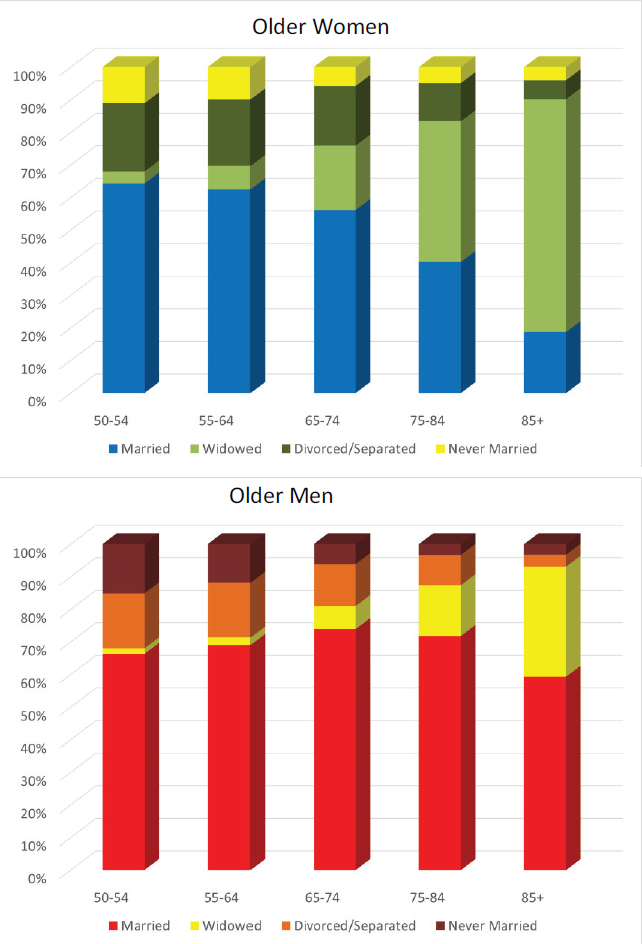

Figure 6-2 shows the distribution by marital status of American men and women ages 65 and older in 2016. Fully 72 percent of men ages 65 and older are currently married, compared with 42 percent of women. Only about 5 percent of men and women never married, and far more women than men are widowed, in part because the female population is older and the loss of spouses rises substantially after age 85.

Cohort Succession

As Matilda White Riley pointed out years ago, the rapidity of demographic change can often lead to a lag in the compensating evolution of social structures (Riley et al., 1994). She was particularly concerned with the ways in which the growth in absolute numbers of older individuals would overtake their opportunities for roles in society. As social changes in family roles and expectations evolved, though, the opposite also has been

SOURCE: Data from tabulations from the 2016 U.S. Current Population Survey.

true: family roles have changed (and become more ambiguous), contributing to a poor fit for older people between their own lives and their roles within families (Dannefer et al., 2005).

One of the key contributions of demographic studies of aging and families is the study of cohort succession and its influence on family relationships. Family transitions in marriage and fertility behavior most often take place at younger ages and affect later-life families through the aging of generations with different norms and histories.

The cohort perspective is particularly important since new cohorts are entering old age with fewer traditional sources of support (spouses and biological children) but more ex-spouses, stepchildren, and surviving siblings. Whereas about 30 percent of ever-married women born in the 1930s divorced by age 60, almost 40 percent of those in the Baby Boom cohorts had divorced at least once (Kreider and Ellis, 2011). The postwar cohorts not only divorced at higher rates when they were younger, they are continuing to do so (Kennedy and Ruggles, 2014). They also were divorcing earlier than previous cohorts and remarrying earlier and more often. Over a quarter of Baby Boom men and women had married more than once by age 55, and almost 10 percent of men and 7 percent of the women had married three times (Lewis and Kreider, 2015).

Changes in childbearing for the cohorts that make up today’s older population and the new cohorts that are aging are shown in Table 6-1. Almost 20 percent of women now in their 50s and 60s have never had children, and only 12 percent have had four or more living children. Coupled with the decline in teen births and the rise in delayed childbearing, new cohorts will reach old age with fewer biological children—and with children who are themselves younger and potentially less independent.

Table 6-1 also shows the detachment of childbearing from marriage.

TABLE 6-1 Cohort Changes in Childbearing among U.S. Women (in percentage)

| Cohort | 1926–1935 | 1936–1945 | 1946–1955 | 1956–1965 | 1966–1975 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childless | 9 | 13 | 17 | 19 | 16 |

| Four+ Children | 37 | 24 | 12 | 11 | 12 |

| Teen First Birth | 23 | 29 | 19 | 18 | 19 |

| 30+ First Birth | 8 | 8 | 19 | 25 | 24 |

| Nonmarital First Birth | 12 | 14 | 16 | 20 | 25 |

SOURCE: Author’s calculations from the U.S. Census Integrated Public Use Microdata Series 1970; Survey of Income and Program Participation, various years; and the Current Population Survey, 2012–2016.

The proportion of women with a nonmarital first birth has risen across cohorts to 25 percent for those born in 1966 or later, and trends show this proportion increasing in younger generations. The popularity of cohabitation and selectivity of marriage have contributed to this trend, and future cohorts will reach old age with children born both in and out of traditional marriage. Much remains unknown about how bonds among family members will evolve in response to this trend. The propensity for and quality of family relationships will undoubtedly be different. As future cohorts age, we can expect to see not only more variation in family structures but also redefined relationships among family members.

Survival, Marriage, and Childbearing Create More Diverse Families

Demographers have shown that increased longevity, lower and later fertility, and serial marriage and partnership yield more-diverse networks of late-life family relationships than in the past. This degree of complexity is likely to grow in the near future. Projecting the distribution of these relationships is difficult. Though we have expanded data collection beyond nuclear families and household boundaries, accounting for family relationships that ended due to death or union dissolution is exceptionally difficult, even with some of our best data resources. Wolf (1994), in the previous publication under this title, and Wachter (1997, 1998) used microsimulation models to estimate the availability of kin under different hypothetical demographic regimes, including nonmarital fertility, divorce, and remarriage. Their studies were among the first to illustrate the expected decline in numbers of biological children available to older men and women and the anticipated increase in stepchildren—especially for men, who remarry more often and to younger women. More recently, Murphy (2010) showed that the proportion of younger adults with stepsiblings could increase from 7 percent in 1950 to 40 percent in 2050.

The understanding of what constitutes “family” within these augmented kin structures is itself undergoing transformation. Cohabitation, sequential partnerships, nonmarital childbearing, and stepparenting have become widespread in younger cohorts. However, these behaviors affect not only those generations but also their older relatives. For example, if an adult child divorces and remarries, one set of grandparents may involuntarily lose access to their grandchildren and the grandchildren may gain a new set of instant grandparents. The norms of these newly expanded families are still being negotiated. Grandparents can be stable relationships for children whose parents divorce, but those ties are also dependent on their relationship with the parent of that grandchild (Hagestad and Uhlenberg, 2007).

THE CONTINUUM OF PROXIMITY TO FAMILY

One of the most important areas of demographic research on aging has been the study of households, living arrangements, and proximity to family members, especially between older parents and their adult children. The first section of this chapter discussed the ways in which demographic changes have been accompanied by a general transition to families with smaller generations and how changes in women’s roles and attitudes about cohabitation and divorce led to more complex extended families. Who lives with whom and the distance between family members is affected not only by these larger family changes but also by economic cycles, housing markets, and changes in the health and care needs of the older population.

Initially, interest in older adults’ living arrangements arose out of concern to identify the most vulnerable elders and determine when family support was available to them. However, while living arrangements are important to understanding family relationships and provide opportunities for support, they are also a framework through which support is given and not necessarily an indicator of support itself. The determinants of co-residence can be complex and differ from decisions to live near family members.

Demographic studies of households were historically constrained by the nature of household surveys, which have difficulty capturing families that cross dwelling boundaries, households with more than one family, or families that live together but do not pool resources. This has particular relevance when looking at multigenerational households, where special arrangements such as “granny flats” may be made within homes but older household members function as a separate unit.

Multiple generations of families often live in close proximity but do not share homes, and nearby family members help with household tasks, such as shopping, housecleaning, cooking, or child care. This has led to much more robust data collection on family proximity, and several national U.S. surveys of aging now provide substantial longitudinal information about family location and characteristics, with especially detailed data on adult children.

It is important to note that though institutionalization rates among the older population are quite low (about 3% for the 65 and older population in the United States), a substantial number of older persons (more than 2 million in 2011) live either in nursing homes or in other residential care facilities (Freedman and Spillman, 2014b). Much research on later-life families commonly still focuses on the community-dwelling population and does not attempt to account for the role of institutionalization in family relations, which is especially important at the oldest ages and

among those with cognitive impairment, for whom institutionalization rates are much higher.

Living Arrangements of the Older Population

Economic independence and improvements in health have contributed to the ability of older persons to live independently (McGarry and Schoeni, 2000). During the 20th century, there was a dramatic rise in the proportion of older people living alone or with a spouse. Many of them live nearby, but not with, their adult children and other family members. From 1960 to 2000 the proportion of older persons living alone rose from 18 to 28 percent. There is some evidence that living alone is declining among older women. From a peak of 38 percent in 1990, the proportion living alone declined to 32 percent in 2014, while for men the corresponding percentage rose slightly from 15 to 18 percent (Stepler, 2016). Older Americans are not the only adults who are increasingly living alone. In the United States, the proportion of all households occupied by single persons rose from 13 percent in 1960 to 28 percent in 2017 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017b).

Table 6-2 shows the distribution of living arrangements for older men and women in the United States in 2015, stratified by marital status. For both men and women, around 80 percent of those with a partner are living independently with that partner and about 14 percent are also living with adult children (and possibly others) in multigenerational households. A very small percentage (< 1%) of married men and women are living alone, mainly because their spouse is institutionalized. Among those not currently married, about two-thirds of both men and women live alone, and the next most common arrangement is living with children. In this case, substantially more women than men (27.6 versus 14.8%) live with adult children, whereas more men live with other relatives or nonrelatives

TABLE 6-2 Living Arrangements of Men and Women, Ages 65 and Older, Living in Households in the Community, United States, 2015 (in percentage)

| Living Arrangement | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmarried | Married | Unmarried | Married | |

| Alone | 67.8 | 1.0 | 63.7 | 0.8 |

| Spouse/Partner Only | — | 79.5 | — | 82.2 |

| Children and Others | 16.4 | 14.8 | 27.6 | 13.4 |

| Others Only | 15.8 | 4.7 | 8.7 | 3.6 |

SOURCE: National Health and Aging Trends Study, weighted tabulations.

(15.8%, compared with 8.7% of women). The overall differences between men and women in living arrangements are largely driven by the differences in their marital status at older ages (shown in Figure 6-2), rather than differential propensities for co-residence.

Multigenerational Households

Declining fertility creates a demographic opportunity for the proportion of vertically extended households to increase (so long as fertility does not fall below replacement level) as the ratio of parents to children approaches unity (Yi, 1986). However, the demographic contributions of population aging to multigenerational households are not necessarily realized when better health and economic independence in later life promote separate living. Households with two or more adult generations have been declining in the United States, but they are more common among minority families and immigrants. In 2012, about 4.6 percent of households were multigenerational, but prevalence was almost twice as high among families with Black or Hispanic householders (8.3% and 8.6% respectively) (Vespa et al., 2013).

Families have been doubling up in part because of downward mobility among younger adult generations, a trend that was exacerbated by the recession in 2007 (Treas and Sanabria, 2016). Multigenerational households are often formed in response to needs for child care or to pool resources in the face of economic hardship (Harrington Meyer and Kandic, 2017). These households are as likely to have multiple families in the same generation (for instance, when adult siblings move in together) as to be multigenerational (Pilkauskas et al., 2014). Older immigrants in the United States are also far more likely to live in multigenerational households as a result of family reconstitution policies that allowed older family members to immigrate to join adult children and grandchildren (van Hook and Glick, 2007).

Geographic Proximity

There is a perception in the United States and many Western countries that occupational mobility and national job markets have increased internal migration, and thus families are more geographically dispersed than in the past, creating a potential threat to old age support if family members are not close enough to provide hands-on care. However, research beginning in the 1990s examined the dispersion of families and showed that over three-quarters of older parents live within 1 hour travel time of a child, and many live even closer (e.g., Clark and Wolf, 1992; Lin and Rogerson, 1995). This pattern has persisted over several decades; Raymo and colleagues (2017) used recent HRS data to show that 45 percent of men and women ages

65 and older lived within 10 miles of an adult child. Similar findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe surveys show 85 percent of older parents in Europe had a child living within 25 km in 2004 (Hank, 2007). These levels of close proximity are borne out in studies from the adult children’s perspective. Compton and Pollak (2013), using 1996 data, found that 40 percent of married couples, ages 25 and older, live within 30 miles of both the husband and wife’s parents. Chan and Ermisch (2015) found similar levels of proximity in the United Kingdom in 2010, with almost two-thirds of couples living less than an hour travel time to an older parent. High rates of close proximity between older parents and their children do not reflect moves to become closer at later ages, as one would suspect in highly mobile societies. Rather, Wolf and Longino (2005) showed that the majority of job-related moves among children take place long before parents need care, and most people do not move far from their place of birth. Most older people therefore also stay in close proximity to at least one sibling (Miner and Uhlenberg, 1997; White, 2001).

Although data on proximity is substantially better than two decades ago, we are still limited in our ability to understand the geography of later-life families, especially the location of children and other relatives in relation to each other, since survey data are collected with measures relative to a focal individual. We also have difficulty identifying short-distance moves (e.g., within the closest category of noncoresidential proximity), and we know little about the reasons that older adults or their children move.

Determinants of Family Co-residence and Proximity

A key contribution of demographers to understanding family geography is that proximity and co-residence are necessarily conditioned on the demographic availability of kin (Wolf, 1984). The spatial distribution of families therefore must be based on propensities for persons who have the option of living near or with a particular category of relative (e.g., Ruggles, 1987; Martin, 1989; Wolf, 1994). Living arrangements and family distance are the product of decisions made across many different life stages and thus can be difficult to model. Demographic research has examined the characteristics of family members that are associated with different living arrangements. Beginning with Wolf and Soldo in 1988, the availability and characteristics of both older parents and their children were explicitly included in household and care models. Pezzin and Schone (1999) used game theory models to incorporate different preferences for co-residence between parents and multiple children, and many others have followed.

Proximity and co-residence with children is often assumed to be sensitive to the needs of older adults, especially health events. However, evidence has been conflicting. Cross-sectional studies consistently report a

higher prevalence of co-residence with children among older adults in ill health (e.g., Wolf and Soldo, 1988; Silverstein, 1995; Compton and Pollak, 2013). Choi et al. (2015) found cardiovascular events related to decreases in distance between parents and children, but others found no relationship between parents’ needs and proximity (Rogerson et al., 1993). Later timing of parenthood means some older adults are living with children who have never left home for reasons unrelated to health (Clark and Wolf, 1992; Wiemers et al., 2017a).

A small number of studies have looked at parent-child proximity from a dynamic perspective, examining moves or changes in proximity relative to various determinants. Painter and Lee (2009) found that older parents in the United States were more likely to remain in their home if they had children living in the same state. Zhang et al. (2013) showed that adult children were more likely than their parents to make a proximity-enhancing move, especially in response to a parent’s illness or their own economic needs. In the United States and Germany, older parents’ moves are associated with good health and young grandchildren (Zhang et al., 2013; Winke, 2017). Evidence in all these cases is quite indirect, and more needs to be done to understand the motivations underlying family mobility

CARE-GIVING

As other chapters in this volume discuss in more detail, increased longevity has been accompanied by improvements in health and functioning at later ages, leading to longer lives lived independently. Despite this, many older individuals eventually need assistance with day-to-day activities, and family members are the most common and consistent source of care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). Care-givers help with chronic disease management, basic self-care, and household tasks; they also provide emotional support.

Despite the dominance of family care-givers in informal care networks, relatively few efforts have been made to collect data about the family members who provide help (Wolff and Kasper, 2006). In part, identifying the universe of caregivers has been problematic (Giovanetti and Wolff, 2010). Family members who provide help to older members do not always identify themselves as care-givers, and measuring assistance in families can be challenging. Family members help each other, doing household tasks unrelated to health and from which everyone in the family may benefit. Freedman et al. (2014) addressed some of these issues for spousal care-giving with time-use diary data from the PSID. They found that both husbands and wives engaged in care activities for their spouse but that wives did household chores two to three times more often than husbands.

A long and robust literature has established that spouses and adult

children are the most common family members to provide care and that the proportion of informal caregivers that are children has been rising since the 1990s (for reviews, see Silverstein and Giarrusso, 2010; Spillman and Pezzin, 2000; Wolff and Kasper, 2006). According to the U.S. National Health and Aging Trends Study, in 2011 spouses represented 21 percent of informal care-givers, 29 percent were daughters, and 18 percent were sons (Freedman et al., 2014). These figures are not additive since care can be provided by a combination of care-givers, but most older persons receive help from only one or two informal helpers at any given time (Freedman and Spillman, 2014a). Wives are more likely to provide assistance, spend more time, and help with more tasks than husbands (Stoller and Miklowski, 2008). However, in 2015 husbands represented about 45 percent of spousal care-givers and committed substantial amounts of time to care-giving (Wolff et al., 2017). Other family members, such as siblings and grandchildren, play a lesser role but may be called upon when the mainstays of the care arrangements are not available. Siblings can be important care-givers for older persons who are childless, and they play a role in deferring institutionalization (Freedman, 1996).

As health has improved and mortality has declined, the age at which care is needed has been delayed until quite late in life. Given that today’s oldest old had children relatively young, not only are spouse care-givers quite elderly but adult children also may be near or in old age when they are called upon to help their parents. Almost 13 percent of care-givers were age 65 or older during the 1990s (Wolff and Kasper, 2006); since 1999, the proportion of care-givers ages 65–74 has grown slightly from 24 to 32 percent (Wolff et al., 2017).

Older adults are not merely recipients of family help; they also provide help to children and grandchildren. Financial support generally flows downward across generations until quite late in life, and parents are highly responsive to adult children’s needs for financial assistance (Schoeni, 1997; McGarry, 2016). In addition, most grandparents are engaged with their grandchildren, providing emotional support and child care, with a small but important proportion acting as primary care-givers to grandchildren in the absence of parents (Casper et al., 2016).

“Sandwich” Care-giving

Later childbearing and longer survival also increase the potential for “sandwiched” generations. The term was coined to describe the potential for middle-aged adults to be engaged in care-giving for generations above and below them. The most important demographic predictors of dual care-giving are the timing of care needs among older parents and the length of generations in families. Most adults providing care to parents

have children who are independent adults. A minority of women (between 10% and 30%) are estimated to be providing support simultaneously to parents and children (Soldo, 1996; Agree et al., 2003; Grundy and Henretta, 2006; Friedman et al., 2016). While this pattern is not dominant, women with college educations tend to marry and begin childbearing later, extending the length of generations in these families and putting them at greater risk of having a child at home when they need to care for an older parent (Agree et al., 2003). As the older population becomes more educated, there is likely to be some increase in such dual-support responsibilities.

Role of Kin Availability

Since care-givers to older persons are almost always spouses or adult children (or both), past fertility and marriage patterns play a large role in establishing the demographic availability of these types of close kin. As much as 90 percent of older men and women who are married depend on their spouses, and unmarried older persons most likely have a child (usually a daughter) on the front lines of care (Spillman and Pezzin, 2000; Freedman et al., 2004). Larger families have a greater choice among siblings, and studies show that care is shared and negotiated within families (e.g., Wolf et al., 1997; Pezzin and Schone, 1999; Checkovich and Stern, 2002). Pezzin and colleagues (2014) illustrated the complexities of care negotiations among siblings, showing that when a parent co-resides with one child it reduces the care received from non-co-resident siblings.

The high divorce rates and low fertility that characterize the aging Baby Boom cohorts are likely to bring with them differences in support and caregiving (Ryan et al., 2012). Most research on family care-giving has focused on spouses, sons, and daughters, but the role of siblings, friends, and more distant relatives may grow.

COMPLEX FAMILIES AND LATER-LIFE SUPPORT

Union formation and dissolution and childbearing occur at younger ages and affect late-life families through complex marital and fertility histories that create large, diffuse sets of kin relationships with ill-defined norms about support. Concerns persist that the rising numbers of nontraditional family relationships will contribute to a deterioration in family support for older persons and jeopardize the well-being of future cohorts as they age. The underlying assumption is that nontraditional family roles and structures are associated with rejection of traditional norms of family support. Alternately, as cohabitation and divorce become more acceptable, the tolerance for a variety of family forms could increase, and changing gender

roles may strengthen family bonds as both men and women invest more time with their children (Bianchi et al., 2006). The same changes contributing to the rise in divorce and family instability in past decades could thus improve the ability of families to care for older generations in the future (Goldscheider et al., 2015).

There is a growing literature examining the consequences for support of parents, but it may take some time before empirical evidence accumulates of family adaptation at older ages; even today the proportion of older persons who have remarried and have stepchildren is quite low. Furthermore, surveys rarely collect information on past relationships, so limited information is available on ex-spouses and stepchildren in studies of health and aging. Estimates from a 2013 PSID special module that collected extensive family information showed about 2 percent of those ages 55 and older with a living stepparent, but about 13 percent of women and 18 percent of men had stepchildren3 (Wiemers et al., 2016).

Studies most commonly show that divorce and remarriage are associated with less intergenerational contact, support, and relationship quality in comparison to those in long-term intact marriages (e.g., Furstenberg et al., 1995; Grundy and Shelton, 2001; Kalmijn, 2007; Noël-Miller, 2013; Pezzin and Schone, 1999; Shapiro, 2012). Divorced fathers are particularly vulnerable; they co-reside with adult children less often and receive fewer hours of informal care from them. Divorced grandfathers also have less contact with grandchildren and live further from their grandchildren than divorced grandmothers (King, 2003).

Transfers of support within families can be a function of need as well as preferences. Family members who are separated or divorced have more needs for financial support and care than those with a partner, and they receive more help (Glaser et al., 2008; Kalmijn, 2016). This is consistent with studies showing that remarried parents have weaker ties with children from prior relationships. Kalmijn (2013, 2015) found that adult children had less contact, less support, and poorer quality relationships with repartnered fathers than with fathers who remained divorced and lived alone.

Not surprisingly, just as interest in aging families has often focused on the availability of children for care-giving, research on the impact of divorce and remarriage has focused on the relationship between stepchildren and stepparents. Stepchildren are less likely to live near or with stepparents in later life, they provide less support (of all kinds) than biological children,

___________________

3 Unfortunately, while it is an improvement over previous data collection, the PSID sample only collects stepparent information for respondents with living biological parents and only collects stepchild information for those currently in a union, so these figures likely underestimate the prevalence of stepkin.

and they receive less from stepparents (Seltzer et al., 2012). The greater numbers of kin added to families by stepparents and stepchildren does not appear to make up for the lower amount of support provided in these families (Wiemers et al., 2017b). Health outcomes for older stepparents may be worse as well. Both men and women with only stepchildren experienced greater disability and higher mortality than those with biological children alone. Interestingly, stepchildren appear beneficial for older women’s health when biological children are present (Pezzin et al., 2013).

Family members in complex families are often linked through other individuals. For example, stepchildren are tied to a stepparent because of that person’s relationship to their biological parent. Their relationship can differ depending on whether the biological parent is present and the closeness of that relationship. When an adult child’s biological parent is alive, more care is given to the stepparent. Correspondingly, the presence of children (biological or step) increases the hours of care provided by spouses (Pezzin et al., 2009).

Support between parents and stepchildren also depends on the quality of the relationships in the family. We generally view these ties as more volitional and less obligatory than traditional nuclear family ties, but we have few tools to understand the variation within these families in their support. Current research is limited both by gaps in information about the extensive set of quasi-kin in complex families, and because we know little about the early-life antecedents that shape relationships with stepparents or half-siblings.

A few studies have examined differences in the quality of stepchild and stepparent relations. While biological children begin their relationships with parents at birth, stepchildren meet their stepparents at the time their parents marry. Research on younger adults has shown that the closeness between adolescents and their stepparents in adulthood is related to the quality of the biological parent’s relationship to that parent’s new spouse (King and Lindstrom, 2016). Some late-life studies show that stepchildren who lived during their childhood with the stepparent receive levels of support equivalent to that received by biological children (Pezzin and Schone, 1999; Kalmijn, 2013). Other evidence suggests that stepchildren who were older at the time their parents married were more likely to receive financial support in adulthood (Henretta et al., 2014). Reconciling these conflicting findings will require more data on complex families, with information about marital histories and these diverse sets of kin.

NEW FORMS OF FAMILY

Most family dynamics take place at young ages, when unions are being formed for independence and reproduction. Yet divorce, remarriage,

cohabitation, and other forms of partnering have been rising among midlife and older adults. Additionally, recent changes in U.S. law recognize same-sex marriage nationally, with consequences for older couples across the United States.

Late-Life Cohabitation

Cohabitation has been increasing at all ages in the United States, including among older adults. Just as the Baby Boom cohorts were more accepting of divorce earlier in life, they also are more open to cohabiting than earlier generations, and the proportions in these unions are expected to increase (Brown and Wright, 2015). The proportion of those ages 55 and older cohabiting with an opposite-sex partner rose from 8 percent of men and 6 percent of women in 2000 to 14 and 12 percent, respectively, in 2012 (Vespa et al., 2013). The majority of older cohabiters are previously divorced (85% in 2015), and many have children (Stepler, 2017; Brown and Wright, 2017). Unlike youthful cohabitations, late-life cohabitations are longer and more stable, which is consistent with the latter being less of a stepping-stone to marriage and more of an alternative to legal union (Brown et al., 2012).

The reasons older cohabiters choose not to marry are less well known. Some may not want to take the financial risks involved in legal marriage at a time when many are living on pension income or savings but prefer the companionship and cost effectiveness of living with a romantic partner. About a third of cohabiters in one study reported planning bequests to family members unrelated to their partner, and cohabitation may be a way of protecting these bequests (Vespa, 2012). As marriage becomes more selective for education, cohabitation has been growing primarily among those of lower SES, especially among those with less than a high school education. Older cohabiters appear to be similar in their profile: 49 percent of older cohabiters had a high school education or less (compared with 40% of those who remarried) and 21 percent were in poverty (versus only 4% of those who remarried) (Brown and Wright, 2017; U.S. Census Bureau, 2016).

Living Apart Together

An alternative to cohabitation, called “living apart together” or LAT, is defined as a committed romantic relationship in which both partners maintain separate households. It is more established in Europe than in the United States. The age distribution of LAT relationships is highly skewed toward younger ages. In the United Kingdom, over one-half were under the age of 25, but 8 percent of women ages 50–59 reported a regular partnership with someone they did not live with (Haskey, 2005). In France, older

men were less likely than women to be in LAT relationships and more likely to cohabit (Régnier-Loilier et al., 2009).

As one would expect, given the expense of maintaining separate households in a committed relationship, individuals in LAT relationships tend to be better educated, more egalitarian, have higher incomes, and value autonomy (Strohm et al., 2009). Women report LAT as a way to maintain independence in a relationship, rather than conforming to gendered expectations (Haskey and Lewis, 2006). Older adults may enter into LAT relationships to avoid financial entanglements, especially when they have children, and to limit the impact if and when the relationship ends. Having been divorced, number of past unions, and presence of adult children were characteristics positively associated with LAT relationships at older ages in the Netherlands and France (de Jong Gierveld, 2004; de Jong Gierveld and Merz, 2013; Régnier-Loilier et al., 2009). In the United States, studying LAT relationships is hampered by lack of data on couple relationships and on same-sex partnerships (Strohm et al., 2009). It is also difficult to define LAT couples as distinct from a less-committed form of “dating” (de Jong Gierveld and Merz, 2013).

Same-Sex Relationships

With the Obergfell decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in June 2015, same-sex marriage became legal across the United States. Although it had been legal in a number of states before that, it was now possible for same-sex couples to receive the protections of legal marriage across the country. Same-sex spouses gain access to health insurance and other legal benefits in marriage. They have rights to more fully participate in medical decisions for a spouse. They also can be more secure in obtaining retirement or survivor benefits under Social Security in cases of divorce or death.

Obergfell was the culmination of a rapid change in popular attitudes about same-sex relationships and gender identity. In 2001, only 35 percent of American adults approved of same-sex marriage. By 2017, this proportion had risen to 62 percent, and 56 percent of Baby Boomers were in favor (Pew Research Center, 2017). As same-sex relationships became more widely accepted, the numbers of same-sex couples reported in surveys quintupled from 145,000 in 1990 to 1.1 million in 2016 (Romero, 2017). In the latter half of 2015, the percentage of new marriages that were same-sex unions rose from 6 percent pre-decision to 11 percent post-decision (Gates and Brown, 2015). According to the Williams Institute, the number of married same-sex couples has risen from about 390,000 in 2015 to 547,000 in 2017 (Romero, 2017). That legal marriage was now an option implies that a substantial number of older, established same-sex couples may be marrying. Statistics on older same-sex couples are limited, but the American Community Survey

estimated that in 2016, 26 percent of unmarried and 42 percent of married same-sex couple households had a partner ages 55 and older.4

DIVERSITY

Socioeconomic inequality is central to understanding the present and especially the future of family change. The demographic trends described in this chapter are quite different for various segments of the population. Those without a college education and engaged in “blue-collar” work are more likely to have earlier, multipartner fertility. Couples with less education are also more likely to cohabit instead of marrying and to have a nonmarital first birth. Traditional marriage is increasingly becoming the province of the college educated (Carlson and England, 2011; Furstenberg, 2014). Educational differences are already being seen in the generational structure of families. The proportion of adults ages 75 and older with four sets of grandchildren was twice as great among those without a high school degree (38%) as for the college educated (19%) (Seltzer and Yahirun, 2014).

Social class differences affect multiple generations in families through many pathways. Older adults with a college education are more likely to give financial support to adult children—probably because they are financially better off—and children with a college education or more provide greater assistance to aging parents (McGarry and Schoeni, 1995). Grandparents who are primary care-givers for grandchildren are more likely to be in or near poverty, and poor areas with high multigenerational co-residence rates have more pneumonia and influenza hospitalizations at older ages (Cohen et al., 2011). There is also evidence that poor grandparental education is associated with low birth weight among grandchildren (McFarland et al., 2017).

Another important source of stratification among late-life families in the United States is race/ethnicity. While today’s older population is less diverse than upcoming cohorts, minority families tend to be younger, have higher fertility, and live in multigenerational family households (Seltzer and Yahirun, 2014). Grandparents who live in these multigenerational households are often providing the household chores and child care for single parents or couples with two jobs (Treas and Marcum, 2011). African American elders who live with others tend to be among the poor-

___________________

4 Statistics derived by author from the 2016 American Community Survey detailed tables, “Table 2. Household Characteristics of Same-Sex Couple Households by Relationship Type.” Available: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/same-sex-couples/ssc-house-characteristics.html [April 2018].

est and more often live with children out of economic necessity (Seltzer and Yahirum, 2014).

Older immigrants face unique challenges. While many came to the United States when they were younger, a substantial number are joining adult children through family reunification programs. They face unfamiliar new cultures and language problems, and they are often ignored by younger family members, who are busy and whose lifestyles are often quite different (Treas and Mazumdar, 2002). In some cases, policies that reduce benefit eligibility for noncitizens make immigrant elders completely dependent on children (Treas and Gubernskaya, 2015). Older immigrants who become naturalized are more likely to live on their own (Lee and Angel, 2002).

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Demographic change is both predictable and completely unknown. In the case of population aging, the slow increases in longevity over the past century were observable and well documented. The inevitable growth in the size and share of the population at older ages was clear. Yet, the implications of these age structure changes have been broadly debated and far less well understood. In particular, the aging of the population is interwoven with the process of family change. The gender revolution began 50 years ago, and yet its corresponding effects on fertility, marriage, and the quality of family relationships are still being evaluated. Studies that focus solely on the older population have to some extent been able to sidestep these questions for many years because gender role transformations largely affected men and women at younger ages. Now, as the cohorts at the forefront of these revolutions are themselves entering old age, there is a surge in interest about the implications of changing family structure and relationships for well-being in later life.

In this chapter, the demographic components of family change and the implications for family structure, co-residence, and support have been reviewed. One of the reasons this research is possible is the availability of family roster data and marital histories in surveys of aging. Many of the studies cited here use data from the HRS family of surveys, the PSID roster on generations and transfers, or the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Each of these sources has extended our knowledge about aging families and their relationships. Yet gaps in knowledge remain with regard to past (dissolved) relationships and early-life family circumstances. Projects that connect information about individuals’ childhood circumstances and their reproductive and marital histories will be helpful in filling in some of the remaining gaps.

Another less-well-understood trend is the bifurcation of family lives by social class and by race/ethnicity. Overall trends in family change obscure

substantial differences in marriage and fertility experienced by those in different social and economic positions, especially between those with different levels of education. These differences create unique vulnerabilities for those at the lower end of the SES distribution, since they tend to form families through less stable and more varied partnerships. More needs to be understood about these differences, but oversampling is rarely done in surveys on aging for minority elders or those in poverty or low income, and studying these families relies on specialized datasets and on small-scale or qualitative research.

Demographic changes in families are not only a function of normative social changes but also respond to economic policy and technological change. There is a growing set of studies that have examined the way in which national- and state-level policies, the availability of formal care services, and new technologies may affect the ways in which families live and care for each other, but these topics were beyond the scope of the chapter for this volume.

Finally, the emerging forms of families, such as large sets of quasi-kin, nonmarital partnerships, or same-sex marriages (many now with their own children), provide a fruitful area for further research. The transformation of gender and family roles that has led to this explosion of variety in family types and relationships, and the erosion of stereotypes about what families are and “should” be, allows researchers to develop new models and theoretical understanding of how kinship networks function and what old age means in these new and evolving families.

REFERENCES

Agree, E., Bissett, B., and Rendall, M.S. (2003). Simultaneous care for parents and care for children among mid-life British women and men. Population Trends, 112, 29–35.

Agree, E.M., and Hughes, M.E. (2012). Demographic trends and later life families in the 2lst century. In R. Blieszner and V.H. Bedford (Eds.), Handbook of Families and Aging, 2nd ed. (pp. 9–33). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Bachu, A. (1999). Trends in premarital childbearing: 1930–1994. In Current Population Reports (pp. 23–197). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Bengtson, V.L. (2001). Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1–16.

Bianchi, S.M., Robinson, J.P., and Milke, M.A. (2006). The Changing Rhythms of American Family Life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Brown, S.L., and Lin, I.F. (2012). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(6), 731–741.

Brown, S.L., and Wright, M.R. (2015). Older adults’ attitudes toward cohabitation: Two decades of change. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(4), 755–764.

Brown, S.L., and Wright, M.R. (2017). Marriage, cohabitation, and divorce in later life. Innovation in Aging, 1(2). doi: 10.1093/geroni/igx015.

Brown, S.L., Bulanda, J.R., and Lee, G.R. (2012). Transitions into and out of cohabitation in later life. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(4), 774–793.

Carlson, M., and England, P. (2011). Social Class and Changing Families in an Unequal America. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Casper, L.M., Florian, S., Potts, C., and Brandon, P.D. (2016). Portrait of American grandparent families. In H. Meyer (Ed.), Grandparenting in the United States (pp. 109–132). Amityville, NY: Baywood.

Chan, T.W., and Ermisch, J. (2015). Proximity of couples to parents: Influences of gender, labor market, and family. Demography, 52(2), 379–399.

Checkovich, T.J., and Stern, S. (2002). Shared caregiving responsibilities of adult siblings with elderly parents. Journal of Human Resources, 37(3), 441–478.

Cherlin, A.J. (2010). The Marriage-Go-Round: The State of Marriage and the Family in America Today. New York: Vintage.

Cherlin, A.J. (2014). Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Choi, H., Schoeni, R.F., Langa, K.M., and Heisler, M.M. (2015). Older adults’ residential proximity to their children: Changes after cardiovascular events. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(6), 995–1004.

Clark, R., and Wolf, D. (1992). Proximity of children and elderly migration. In A. Rogers (Ed.), Elderly Migration and Population Redistribution: A Comparative Perspective (pp. 77–96). London: Belhaven Press.

Cohen, S.A., Agree, E.M., Ahmed, S., and Naumova, E.N. (2011). Grandparental caregiving, income inequality and respiratory infections in elderly U.S. individuals. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 65(3), 246–253.

Compton, J., and Pollak, R.A. (2013). Proximity and Coresidence of Adult Children and their Parents in the United States: Description and Correlates (IZA Discussion Paper #7431). Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Dannefer, D., Uhlenberg, P., Foner, A., and Abeles, R.P. (2005). On the shoulders of a giant: The legacy of Matilda White Riley, Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(6), S296–S304.

de Jong Gierveld, J. (2004). Remarriage, unmarried cohabitation, living apart together: Partner relationships following bereavement or divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(1), 236–243.

de Jong Gierveld, J., and Merz, E.M. (2013). Parents’ partnership decision making after divorce or widowhood: The role of (step) children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(5), 1098–1113.

Freedman, V.A. (1996). Family structure and the risk of nursing home admission. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 51B (2), S61–S69.

Freedman, V.A., and Spillman, B.C. (2014a). Disability and care needs among older Americans. Milbank Quarterly, 92(3), 509–541.

Freedman, V.A., and Spillman, B.C. (2014b). The residential continuum from home to nursing home. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 69(7), S42–S50.

Freedman, V.A., Aykan, H., Wolf, D.A., and Marcotte, J.E. (2004). Disability and home care dynamics among older unmarried Americans. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 59, S25–S33.

Freedman, V.A., Cornman, J.C., and Carr, D. (2014). Is spousal caregiving associated with enhanced well-being? New evidence from the PSID. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(6), 861–869.

Friedman, E.M., Park, S.S., and Wiemers, E.E. (2016). New estimates of the sandwich generation in the 2013 PSID. Gerontologist, 57(2), 191–196.

Furstenberg, F. (2014). Fifty years of family change: From consensus to complexity. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654(1), 12–30.

Furstenberg, F., Hoffman, S., and Shrestha, L. (1995). The effect of divorce on intergenerational transfers: New evidence. Demography, 32(3), 319–333.

Gates, G., and Brown, T.N. (2015). Marriage and Same-Sex Couples after Obergefell. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute.

Giovannetti, E.R., and Wolff, J.L. (2010). Cross-survey differences in national estimates of numbers of caregivers of disabled older adults. Milbank Quarterly, 88(3), 310–349.

Glaser, K., Stuchbury, R., Tomassini, C., and Askham, J. (2008). Long-term consequences of partner-ship dissolution for support in late life in the United Kingdom. Ageing & Society, 28(3), 329–351.

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., and Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding family demographic behavior. Population & Development Review, 41(2), 207–239.

Grundy, E., and Henretta, J.C. (2006). Between elderly parents and adult children: A new look at the intergenerational care provided by the “sandwich generation.” Ageing & Society, 26(5), 707–722.

Grundy, E., and Shelton, N. (2001). Contact between adult children and their parents in Great Britain 1986–99. Environment and Planning A, 33(4), 685–697.

Hagestad, G.O., and Uhlenberg, P. (2007). The impact of demographic changes on relations between age groups and generations. In K. Schale and P. Uhlenberg (Eds.), Social Structures: Demographic Changes and the Well-Being of Older Persons (pp. 239–261). New York: Springer.

Hank, K. (2007). Proximity and contacts between older parents and their children: A European comparison. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(1), 157–173.

Harrington Meyer, M., and Kandic, A. (2017). Grandparents in the United States. Innovation in Aging, 1(2), 1–10.

Haskey, J. (2005). Living arrangements in contemporary Britain: Having a partner who usually lives elsewhere and living apart together (LAT). Population Trends, 122, 35–45.

Haskey, J., and Lewis, J. (2006). Living-apart-together in Britain: Context and meaning. International Journal of Law in Context, 2(1), 37–48.

Henretta, J.C., Grundy, E., and Harris, S. (2002). The influence of socioeconomic and health differences on parents’ provision of help to adult children: British–United States comparison. Ageing & Society, 22(4), 441–458.

Henretta, J.C., Van Voorhis, M.F., and Soldo, B.J. (2014). Parental money help to children and stepchildren. Journal of Family Issues, 35(9), 1131–1153.

Hobbs, F., and Stoops, N. (2002). Demographic Trends in the 20th Century (Census 2000 Special Reports, Series CENSR-4). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Kalmijn, M. (2007). Gender differences in the effects of divorce, widowhood and remarriage on intergenerational support: Does marriage protect fathers? Social Forces, 85(3), 1079–1104.

Kalmijn, M. (2013). Adult children’s relationships with married parents, divorced parents, and stepparents: Biology, marriage, or residence? Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(5), 1181–1193.

Kalmijn, M. (2015). Relationships between fathers and adult children: The cumulative effects of divorce and repartnering. Journal of Family Issues, 36(6), 737–759.

Kalmijn, M. (2016). Children’s divorce and parent–child contact: Within-family analysis of older European parents. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 71(2), 332–343.

Kennedy, S., and Ruggles, S. (2014). Breaking up is hard to count: The rise of divorce in the United States, 1980–2010. Demography, 51(2), 587–598.

Kim, K. (2014). Intergenerational transmission of age at first birth in the United States: Evidence from multiple surveys. Population Research and Policy Review, 33(5), 649–671.

King, V. (2003). The legacy of a grandparent’s divorce: Consequences for ties between grandparents and grandchildren. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(1), 170–183.

King, V., and Lindstrom, R. (2016). Continuity and change in stepfather–stepchild closeness between adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(3), 730-743.

Kreider, R.M., and Ellis, R. (2011). Living Arrangements of Children: 2009. (Household Economic Studies). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Lee, G.Y., and Angel, R.J. (2002). Living arrangements and SSI among elderly Asians and Hispanics in the United States: Nativity and citizenship. Journal of Ethnic Migration Studies, 28(3), 553–563.

Lewis, J.M., and Kreider, R.M. (2015). Remarriage in the United States (American Community Survey Reports, ACS-30). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Lin, G., and Rogerson, P. A. (1995). Elderly parents and the geographic availability of their adult children. Research on Aging, 17(3), 303-331.

Lu, L., Chong, Y., Hamilton, B.E., Curtin, S.C., Martin, J.A., Tejada-Vera, B., and Sutton, P.D. (2015). Natality Trends in the United States, 1909–2013. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics.

Margolis, R., and Wright, L. (2017). Older adults with three generations of kin: Prevalence, correlates, and transfers. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences, 72(6), 1067–1072.

Martin, J.A., Hamilton, B.E., and Osterman, M.J.K. (2017). Births in the United States, 2016 (NCHS Data Brief #287). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Martin, L.G. (1989). Living arrangements of the elderly in Fiji, Korea, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Demography, 26(4), 627–643.

Matthews, T.J., and Hamilton, B.E. (2014). First Births to Older Women Continue to Rise (NCHS Data Brief #52). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

McFarland, M.J., McLanahan, S.S., Goosby, B.J., and Reichman, N.E. (2017). Grandparents’ education and infant health: Pathways across generations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(3), 784–800.

McGarry, K. (2016). Dynamic aspects of family transfers. Journal of Public Economics, 137, 1–13.

McGarry, K., and Schoeni, R.F. (1995). Transfer behavior in the Health and Retirement Study: Measurement and the redistribution of resources within the family. Journal of Human resources, 30, S184–S226.

McGarry, K., and Schoeni, R.F. (2000). Social Security, economic growth, and the rise in elderly widows’ independence in the twentieth century. Demography, 37, 221–236.

Miner, S., and Uhlenberg, P. (1997). Intragenerational proximity and the social role of sibling neighbors after midlife. Family Relations, 46, 145–153.

Murphy, M. (2010). Family and kinship networks in the context of ageing societies. In S. Tuljapurkar, N. Ogawa, and A.H. Gauthier (Eds.), Ageing in Advanced Industrial States: Riding the Age Waves (vol. 3, pp. 263–285). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Noël-Miller, C.M. (2013). Repartnering following divorce: Implications for older fathers’ relations with their adult children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(3), 697–712.

Painter, G., and Lee, K. (2009). Housing tenure transitions of older households: Life cycle, demographic, and familial factors. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 39(6), 749–760.

Pew Research Center. (2017). Support for Same-Sex Marriage Grows, Even Among Groups That Had Been Skeptical. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Pezzin, L.E., and Schone, B.S. (1999). Intergenerational household formation, female labor supply and informal caregiving: A bargaining approach. Journal of Human Resources, 34, 475–503.

Pezzin, L.E., Pollak, R.A., and Schone, B.S. (2009). Long-term care of the disabled elderly: Do children increase caregiving by spouses? Review of Economics of the Household, 7(3), 323–339.

Pezzin, L.E., Pollak, R.A., and Schone, B.S. (2013). Complex families and late life among elderly persons: Disability, institutionalization, and longevity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(5), 1084–1097.

Pezzin, L.E., Pollak, R.A., and Schone, B.S. (2014). Bargaining power, parental care, and intergenerational coresidence. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences, 70(6), 969–980.

Pilkauskas, N.V., Garfinkel, I., and McLanahan, S.S. (2014). The prevalence and economic value of doubling up. Demography, 51(5), 1667–1676.

Raymo, J., Pike, I., and Liang, J. (2017). A New Look at the Living Arrangements of Older Americans Using Multistate Life Tables (CDE Working Paper #2017-03). Madison: University of Wisconsin.

Régnier-Loilier, A., Beaujouan, É., and Villeneuve-Gokalp, C. (2009). Neither single, nor in a couple. A study of living apart together in France. Demographic Research, 21, 75–108.

Rendall, M., Weden, M., Favreault, M., and Waldron, H. (2011). The protective effect of marriage for survival: A review and update. Demography, 48(2), 481–506.

Riley, M.W., Kahn, R.L., and Foner, A. (Eds.). (1994). Age and Structural Lag: Society’s Failure to Provide Meaningful Opportunities in Work, Family, and Leisure. New York: Wiley.

Rogerson, P.A., Weng, R.H., and Lin, G. (1993). The spatial separation of parents and their adult children. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 83(4), 656–671.

Romero, A.P. (2017). 1.1 Million LGBT Adults Are Married to Someone of the Same Sex at the Two-year Anniversary of Obergefell V. Hodges. Los Angeles: Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law.

Ruggles, S. (1987). Prolonged Connections: The Rise of the Extended Family in Nineteenth-Century England and America. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Ryan, L.H., Smith, J., Antonucci, T.C., and Jackson, J.S. (2012). Cohort differences in the availability of informal caregivers: Are the Boomers at risk? Gerontologist, 52(2), 177–188.

Schoeni, R.F. (1997). Private interhousehold transfers of money and time: New empirical evidence. Review of Income and Wealth, 43, 423–448.

Schwartz, C., and Mare, R. (2012). The proximate determinants of educational homogamy: First marriage, dissolution, remarriage, and educational upgrading. Demography, 49(2), 629–650.

Seltzer, J.A., and Yahirun, J.J. (2014). Diversity in Old Age: The Elderly in Changing Economic and Family Contexts (UCLA CCPR Population Working Paper). Los Angeles: California Center for Population Research.

Seltzer, J.A., Yahirun, J.J., and Bianchi, S.M. (2012). Doubling up when times are tough: Obligations to share a home in response to economic hardship. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(5), 1164–1180.

Shapiro, A. (2012). Rethinking marital status: Partnership history and intergenerational relationships in American families. Advances in Life Course Research, 17(3), 168–176.

Silverstein, M. (1995). Stability and change in temporal distance between the elderly and their children. Demography, 32(1), 29–45.

Silverstein, M., and Giarrusso, R. (2010). Aging and family life: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1039–1058.

Soldo, B.J. (1996). Cross pressures on middle-aged adults: A broader view. Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 51(6), S271–S273.

Spillman, B.C., and Pezzin, L.E. (2000). Potential and active family caregivers: Changing networks and the “sandwich generation.” Milbank Quarterly, 78(3), 347–374.

Stepler, R. (2016). Smaller Share of Women Ages 65 and Older Are Living Alone: More Are Living with Spouse or Children. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Stepler, R. (2017). Number of U.S. Adults Cohabiting with a Partner Continues to Rise, Especially Among Those 50 and Older. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Stoller, E.P., and Miklowski, C.S. (2008). Spouses caring for spouses: Untangling the influences of relationship and gender. In M. Szinovacz and A. Davey (Eds.), Caregiving Contexts: Cultural, Familial, and Societal Implications (pp. 115–131). New York: Springer.

Strohm, C.Q., Seltzer, J.A., Cochran, S.D., and Mays, V.M. (2009). “Living apart together” relationships in the United States. Demographic Research, 21, 177–214.

Treas, J., and Gubernskaya, Z. (2015). Policy contradictions and immigrant families. Public Policy & Aging Report, 25(3), 107–112.

Treas, J., and Marcum, C.S. (2011). Diversity and family relations in an aging society. In R.A. Settersten and J.L. Angel (Eds.), Handbook of Sociology of Aging (pp. 131–141). New York: Springer.

Treas, J., and Mazumdar, S. (2002). Older people in America’s immigrant families: Dilemmas of dependence, integration, and isolation. Journal of Aging Studies, 16(3), 243–258.

Treas, J., and Sanabria, T. (2016). Marital status and living arrangements over the life course. In M.H. Meyer and E.A. Daniele (Eds.), Gerontology: Changes, Challenges, and Solutions (pp. 247–270). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger

U.S. Census Bureau. (2016). Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2017a). Current Population Survey, June 1976-2016. Historical Tables. Available: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/fertility/time-series/his-cps [November 2017].

U.S. Census Bureau. (2017b). Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements, 1960 to 2017. Available: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/households.html [November 2017].

van Hook, J., and Glick, J.E. (2007). Immigration and living arrangements: Moving beyond economic need versus acculturation. Demography, 44(2), 225–249.

Vespa, J. (2012). Union formation in later life: Economic determinants of cohabitation and remarriage among older adults. Demography, 49(3), 1103–1125.

Vespa, J., Lewis, J.M., and Kreider, R.M. (2013). America’s families and living arrangements: 2012. Current Population Reports, 20, P570.

Wachter, K.W. (1997). Kinship resources for the elderly. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 352(1363), 1811–1817.

Wachter, K.W. (1998). Kinship Resources for the Elderly: An Update. Berkeley: University of California.

White, L. (2001). Sibling relationships over the life course: A panel analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 555–568.

Wiemers, E.E., and Bianchi, S.M. (2015). Competing demands from aging parents and adult children in two cohorts of American women. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 127–146.

Wiemers, E.E., Seltzer, J.A., Schoeni, R.F., Hotz, V.J., and Bianchi, S.M. (2016). The Generational Structure of U.S. Families and their Intergenerational Transfers (UCLA CCPR Population Working Paper). Los Angeles: California Center for Population Research.

Wiemers, E.E., Slanchev, V., McGarry, K., and Hotz, V.J. (2017a). Living arrangements of mothers and their adult children over the life course. Research on Aging, 39(1), 111–134.

Wiemers, E.E., Seltzer, J.A., Schoeni, R.F., Hotz, V.J., and Bianchi, S.M. (2017b). Stepfamily Structure and Transfers between Generations in the United States. Available: http://public.econ.duke.edu/~vjh3/working_papers/StepkinTransfers.pdf [April 2018].

Winke, T. (2017). Later life moves and movers in Germany: An expanded typology. Comparative Population Studies, 42, 3–24.

Wolf, D.A. (1984). Kin availability and the living arrangements of older women. Social Science Research, 13(1), 72–89.

Wolf, D.A. (1994). The elderly and their kin: Patterns of availability and access. In National Research Council, Demography of Aging (pp. 146–194). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Wolf, D.A., and Longino, C.F., Jr. (2005). Our “increasingly mobile society”? The curious persistence of a false belief. Gerontologist, 45(1), 5–11.

Wolf, D.A., and Soldo, B.J. (1988). Household composition choices of older unmarried women. Demography, 25(3), 387–403.

Wolf, D.A., Freedman, V., and Soldo, B.J. (1997). The division of family labor: Care for elderly parents. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 52(Spec. Issue), 102–109.

Wolff, J.L., and Kasper, J. (2006). Caregivers of frail elders: Updating a national profile. Gerontologist, 46(3), 344–356.

Wolff, J.L., Mulcahy, J., Huang, J., Roth, D.L., Covinsky, K., and Kasper, J.D. (2017). Family caregivers of older adults, 1999–2015: Trends in characteristics, circumstances, and role-related appraisal. Gerontologist. doi: 0.1093/geront/gnx093.

Yi, Z. (1986). Changes in family structure in China: A simulation study. Population and Development Review, 12(4), 675–703.

Zhang, Y., Engelman, M., and Agree, E.M. (2013). Moving considerations: A longitudinal analysis of parent-child residential proximity for older Americans. Research on Aging, 35(6), 663–687.