5

Place, Aging, and Health

Kathleen A. Cagney1

and

Erin York Cornwell2

INTRODUCTION

Aging in place suggests the goal of many older adults to age within the long-term residence or community where they have spent much of their adult lives. However, this concept also recognizes that aging is a process that occurs within a particular place. Whether older adults reside in their long-term communities or move to other locations, the characteristics of the places within which they experience the aging process—and the psychosocial and quality-of-life benefits potentially conferred by these places—likely have profound consequences for their abilities to adapt to changes such as bereavement, retirement, and deteriorating health, as well as their capacity to recover from illness (Latham et al., 2015) and maintain independent community residence.

What is place, and why does it matter for the lives of older adults? Place suggests a physical space with environmental conditions that may directly impact older adults’ health. Place also encompasses a built environment that may promote or impede mobility and an organizational, institutional, municipal, or policy setting that determines access to resources such as health care, fresh foods, and social services. Importantly, these characteristics of places may also facilitate or impede social interaction and engagement (Hand and Howrey, 2017; Jacobs, 1961; Sampson, 2012). One may readily acknowledge that place likely structures the lives of older

___________________

1 University of Chicago.

2 Cornell University.

adults but an evidence-based understanding of its impact across age, time period, and context is relatively nascent.

In this chapter, we focus on the places that older adults inhabit and the implications of these places for their health. We ask what place means, and we conceive of place as both physical and social. We note that place and its influences may exist in multiple facets, at multiple levels (Andrews et al., 2013), so we focus on both formal and informal conceptions of place. This leads to an exploration of theory and how theory related to place may inform scientific investigations and interpretation of findings. We acknowledge that place can shape opportunity, so we examine how place might lead to such factors as structural inequality and restricted migration. Throughout the chapter, we draw on the extant literature addressing place and bring to bear relevant findings of this body of scholarship to aging and place. We close with new directions in research on place and discuss how potential insights from this work could lead to fundamental reconsiderations of place. This, in turn, may inform how best to exploit the aspects of place that are health enhancing, particularly for older adults.

THE STUDY OF AGING IN CONTEXT

The literature that speaks broadly to place, aging, and health employs various conceptions of place, including nested and overlapping spaces (e.g., states, cities, neighborhoods, locations of daily activities), with consequences for health operating at different scales. While some research takes the definition of place as a relatively straightforward concept, other work theorizes about place and its meaning. In this section, we outline three broad theoretical perspectives that inform much of the research examining place and health in later life: (1) environmental gerontology, (2) geographical gerontology, and (3) social scientific research on “neighborhood effects.”

First, although context has been central to gerontological research since at least the late 1940s (Smith, 2014), the work of Lawton and colleagues was particularly influential in fostering a subdiscipline that acknowledged the influence of place. Lawton and Nahemow’s (1973) Ecological Model of Aging provided a foundation for environmental gerontology by explicitly introducing environmental considerations into research on health and aging, rather than relying solely on a biological framework. Their Ecological Model of Aging “focused on the description, explanation, and modification or optimization of the relation between elderly persons and their sociospatial surroundings” (Wahl and Weisman, 2003, p. 616), elaborating the concept of person–environment fit. This work describes a dynamic relationship between older adults and their living environments: as older adults experience changes in functional capacities, they either adapt themselves

or adapt their surroundings to achieve a balance between their abilities and the demands of their environment. Informed by this perspective, home modifications, nursing services, building design, and new technologies aim to reduce environmental press and thereby promote older adults’ abilities to age in the community (Vasunilashorn et al., 2012).

Psychologists with a focus on aging have been particularly active in developing scholarship in environmental gerontology (e.g., Birren, 1999), drawing out responses to, and perceptions of, physical and social environments including the household. Canter and Craik (1981), in this tradition, later proposed the term “sociophysical environment” to capture the interrelationship between the physical and the social. Moore’s more recent work (2014) proposes an Ecological Framework of Place that incorporates people, place, and activity related to that place, emphasizing the dynamic nature of each. See Wahl and Weisman’s (2003) excellent review of environmental gerontology for a fuller treatment of its origins and contributions.

Second, and roughly over the same period, geography became more central to gerontological concerns (e.g., Golant, 1972; Rowles, 1981). The subfield of geographical gerontology, which has its roots in social geography, emphasizes the interconnectedness and interdependence of spaces and services and underscores the uniquely spatial concerns of older adults (Andrews et al., 2007, 2013). Theories, concepts, and methods of geography are brought to bear on questions related to aging and the life course. One key distinguishing feature is the focus on scale, whether it be within the space of a household, neighborhood, or nation; attention to scale both orients the work and informs the research questions. Some consensus exists, as Cutchin (2009) explicated, that geographical gerontology has not been as impactful as it might. A new text by Skinner and colleagues (2017) aims, in part, to address concerns that geographical gerontology is undertheorized by laying out the theory, analyses, and themes related to geography and its implications for aging. They emphasize the distinguishing features of “place, space, scale, landscape and territory” with the goal of differentiating this work from other research largely aimed at contextual considerations. That is, the conceptual and empirical focus rests with what is distinctly geographical in nature, rather than environmental (e.g., therapeutic landscapes see Winterton, 2017).

Third, a large body of social, scientific, and epidemiological research has been devoted to examining how social context affects health. Early ecological perspectives, associated with the Chicago School, argued that the density and unpredictability of urban environments leads to stress (Simmel, 1903) and erodes the close, personal ties with family members and friends that were presumed to be common in rural areas (Wirth, 1938). These ecological perspectives laid the groundwork for a significant “spatial turn” in later 21st century social scientific research, with the predominant perspec-

tive in this area focused on the assessment of “neighborhood effects.” This work considers characteristics of the local built environment, as well as social factors such as neighborhood composition (e.g., age structure, racial/ethnic heterogeneity), collective properties such as the concentration of poverty or affluence, and contextual factors such as the neighborhood service environment (Subramanian et al., 2006) as well as social cohesion, informal control, and the combined notion of collective efficacy (Sampson, 2012; Sampson and Groves, 1989; Sampson et al., 1997). Sociological research has been particularly concerned with the implications of the neighborhood social context for the health and well-being of older adults who reside there. We describe this work in more detail below.

Research has identified neighborhood effects on individual outcomes across the life course, but some researchers argue that neighborhood conditions may be particularly salient for health and well-being in later life (Robert and Li, 2001). Consistent with the idea of person-environment fit (Lawton and Nahemow, 1973), work in environmental gerontology and sociology emphasizes how life changes such as bereavement, retirement, and the advent of health problems may make older adults especially dependent upon a neighborhood’s physical and social context (Cagney and York Cornwell, 2010; Schieman, 2005). Older adults may also be more vulnerable than younger and middle-aged adults to local physical and environmental conditions (Cannuscio et al., 2003), and they may rely more heavily on opportunities for social integration and support through local institutions such as community-based senior centers and churches or informal interactions with neighbors (e.g., Shaw, 2005; Wethington and Kavey, 2000).

These three broad theoretical approaches—environmental gerontology, geographical gerontology, and neighborhood effects—provide a sense of the more general conceptualizations of the role of place in later life. We now turn to examining various spatial units in which contextual processes may have implications for older adults’ health and well-being. We call attention to research that examines these conventional designations in a novel manner and that incorporates governance and political implications.

SPATIAL UNITS AND INDIVIDUAL HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

Urban, Suburban, and Rural Areas

The three designations of urban, suburban, and rural are a central organizing principle by which researchers have examined place and aging (Shiode et al., 2014; Singh and Siahpush, 2014). Nonmetropolitan or rural areas are defined by exclusion; the Census Bureau defines urbanized areas as those with 50,000 or more people and urban clusters as those with at

least 2,500 and less than 50,000 people. Operational definitions employed at the community level are of course more fluid, as, for instance, traditional rural contexts give way to aspects of suburban development and some older suburbs feel more like a neighborhood of the central city (e.g., Oak Park in Chicago).

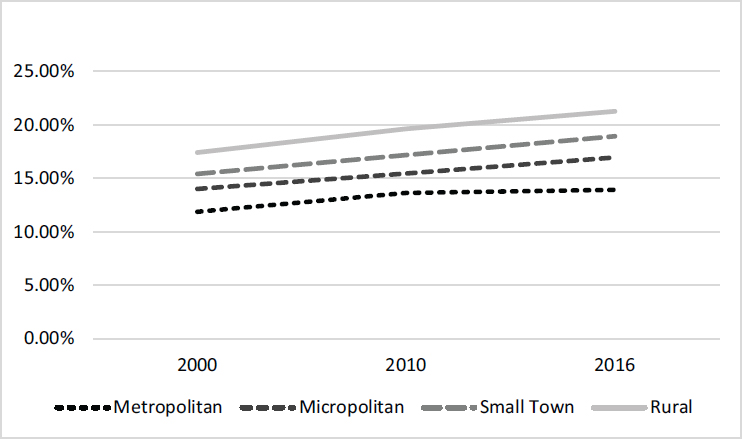

Of particular interest is the difference in the age distribution across these areas. The median age for adults in rural areas is 51, as compared to 45 in urban areas (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). The data in Figure 5-1 indicate that the percentage of the population over age 65 varies across metropolitan, micropolitan, small town, and rural spaces. While all four types of place experienced some growth, the greater share of older adults, and the greatest growth, is in rural areas. Data compiled by the Urban Institute (Pendall et al., 2016) indicate that 15 percent of the rural population was older than 65 between 2000 and 2011, as compared to 13 percent in metropolitan regions. The gap is predicted to widen; estimates suggest that by 2040, 25 percent of rural households will be 65 or older, as compared to 20 percent of urban households. These changes are accompanied by stark differences in population growth as a whole. Between 2020 and 2030, rural population growth is predicted to hover around 1 percent; urban population growth is expected to be approximately 8 percent.

NOTES: Population composition: Metropolitan (50,000 or more), Micropolitan (at least 10,000 but fewer than 50,000), Small Town (at least 2,500 but fewer than 10,000), Rural (all other).

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau.

We note that within the broader category of urban spaces, suburban areas are aging more rapidly than comparatively more-urban spaces. Golant wrote, over 40 years ago, that the older population would be increasingly suburban, surmising that the move to the suburbs to begin a family would not result in a return (Golant, 1975). Now, approximately 8 in 10 of the age 65-plus population live in U.S. metropolitan areas, and nearly two-thirds of these metro dwellers live in the suburbs rather than its central cities (McCarthy and Kim, 2005). Nearly one-half (46%) of our current older suburban population is aged 75 or older, and a further increase in this proportion is expected (Golant, 2009). The structure of most suburban areas—car dependent, clustered commercial spaces, single-family two-story homes—makes aging in that physical environment especially challenging. Furthermore, architects have long argued that the single-family garage has eroded social capital because residents do not have a sight line on one another when entering or exiting a car and thus lack the opportunity to interact informally (e.g., Besel and Andreescu, 2013).

Central to the association of place and age is the ability of communities, particularly rural and suburban ones, to accommodate an aging population both physically and socially. Ecological research suggests that characteristics of urban, suburban, and rural places shape individuals’ abilities to build social networks and access support. Consistent with the theory that densely populated urban areas erode close, personal ties (Wirth, 1938), some studies have found that urban residents have more segmented and smaller networks compared to rural residents (e.g., Hofferth and Iceland, 1998; Curtis White and Guest, 2003). But a recent study finds no difference in network size or the closeness of network ties across older adults living in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas (York Cornwell and Behler, 2015). Data are limited on the extent to which levels of social capital are lower in suburbs compared to cities, but if so, suburban older adults may lack proximal social support when faced with challenges related to navigating their areas and meeting routine needs.

Patterns of urban-rural migration may also contribute to the availability of social and instrumental support for older adults. In China, caregivers in rural areas are often brought in from the Philippines; children have left for job opportunities in urban centers and are not available for the forms of hands-on care needed (Fishman, 2010). A similar dynamic is at play in rural communities of the United States, where out-migration has meant that the pool of informal familial-based caregivers is smaller (Buckwalter and Davis, 2011). Formal long-term care, whether institutional or through home health, may also be more limited in rural areas (Glasgow and Brown, 2012). In the general case, access to health care and formal long-term care varies considerably by context. Residence in a rural location may mean fewer services and longer travel times to obtain needed care (Caldwell et al., 2016).

Nations, States, and Municipalities

Nation and state boundaries can be important not only for service provision but also for political identity and the political economy of place. In the United States, numerous safety net provisions vary by state, making some states more suitable for or attractive to individuals who are in need of support or assistance. States like Utah, Iowa, and South Carolina are often listed as optimal places to grow old, based on estimated cost of living, quality of life, and other factors such as the cost of home health care. Age-related policies and practices also may reflect state-based priorities. Jirik and Sanders (2014), for instance, found substantial variation across states in elder abuse statutes, and the AARP found considerable state-based differences in long-term services and supports, creating an annual scorecard for such measures (Reinhard et al., 2012).

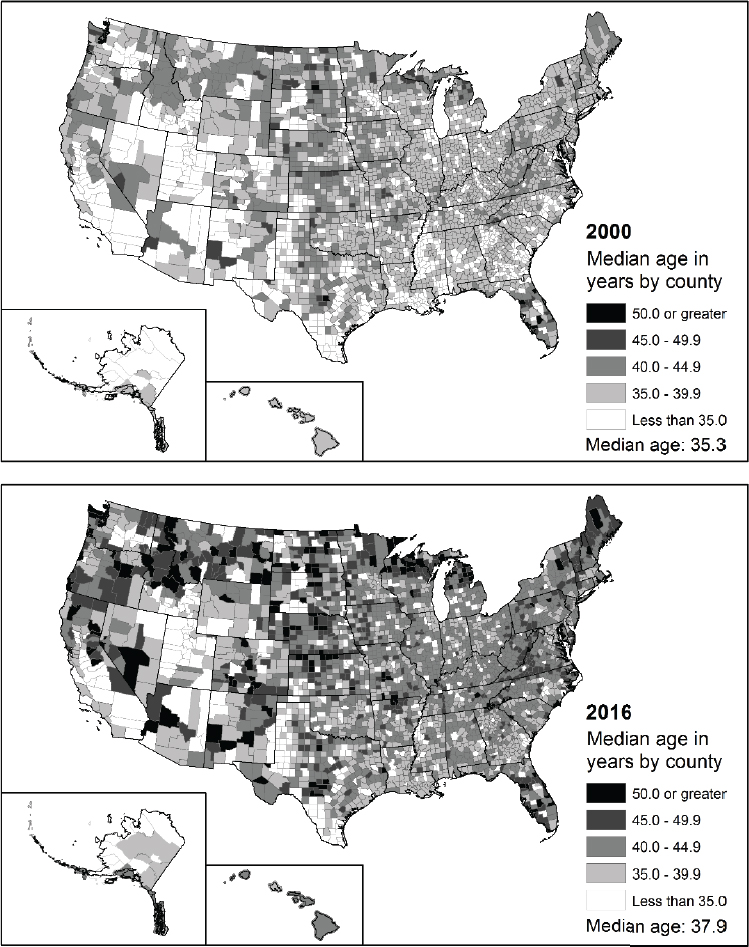

Figure 5-2 indicates that counties and states differ substantially in median age and that this difference has grown dramatically since 2000. We also observe important regional differences in age structure, such that areas of the east coast and north (and some selected areas of the south) have substantially older age structures. Administrative and political boundaries shape governance and resource allocation and may reflect norms related to care of vulnerable populations, including the aged. They also may reflect norms and expectations about older adults in general. To examine the long-held belief that Eastern cultures, as compared to Western, hold the aged in higher esteem, North and Fiske (2015) conducted a meta-analysis (37 papers representing 23 countries) of cross-cultural attitudes toward the aged. They found the highest levels of senior derogation in East Asia and non-Anglophone Europe, and contrary to expectations, they found that cultural individualism, rather than collectivist traditions, predicted positivity toward the aged.

Attitudes toward the aged may also be informed by the psychological well-being that older adults report, and this may indeed be influenced by the structure of supports around them. Hogan et al. (2016) examined happiness as an outcome across key metropolitan areas. They found that the happiness of older residents is associated more with the provision of quality governmental services; these same variables also have an effect on health and social connections, which are then linked to happiness. Steptoe et al. (2015), in an analysis of subjective well-being, found that the U-shaped life evaluation documented in high-income English-speaking countries—that life evaluation dips in middle age and rises again in old age—did not hold in eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Caribbean and Latin America (where life evaluation decreases with age). They further found that, outside high-income English-speaking countries, worry, lack of happiness, and physical pain increase with age; anger and

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau.

stress decrease. Other indicators of emotional well-being also may differ by location and its characteristics. The vast literature on loneliness at older ages (Hawkley et al., 2010) suggests that living alone and social isolation are risk factors (Shaw et al., 2017); these, in turn, may vary by municipal area (e.g., 58% of persons in Stockholm live alone).

Compositional characteristics at the state level may also be consequential for older adult well-being. Novel research in this area illustrates that state-level analyses can be informative. For instance, Montez et al. (2017a) found that disparities in disability by education vary across states, primarily driven by differences in prevalence among those with fewer years of education. In related work, Montez et al. (2017b) found that disability was lower in states with better economic output, greater income equality, longer histories of tax credits for low-income workers, and higher cigarette taxes (for middle-age women). They argued that a state’s socioeconomic and policy contexts appear particularly important for older adults.

Residential Neighborhoods

While the work on neighborhood context and health is too vast to summarize effectively in this chapter, we note that neighborhood influences on health have been documented for physical and mental health, with neighborhood conditions linked to outcomes such as asthma (Cagney and Browning, 2004), obesity (King et al., 2011), coronary heart disease (Diez-Roux et al., 2001), cognitive function (Wight et al., 2006), and mortality (Subramanian et al., 2005). Antecedents to much of this work can be found in early Chicago School research (Browning et al., 2014), with its attention to the structural and social process factors that affect individual- and neighborhood-level outcomes. Social disorganization theory, in particular, elaborates a process through which structural conditions such as concentrated poverty and residential instability (and, to some extent, racial/ethnic heterogeneity) weaken social bonds among neighbors and reduce community involvement. Low-income neighborhoods often lack the foundation for effective social organization, exchanges of support, and informal social control (Sampson, 2012; Wilson, 1987). Connectedness and trust among residents of cohesive neighborhoods may be important for older adults’ health and well-being because they contribute to neighborhood-level collective efficacy, which enables the neighborhood to take action for the common good (Sampson, 2012). They may also enhance the diffusion of health-promoting information within the neighborhood (Cagney and Browning, 2004) and provide just-in-time support, such as assistance during a medical emergency (York Cornwell and Currit, 2016). Neighborhood-level social cohesion has also been associated with greater sense of purpose and meaning in life (Kawachi and Berkman, 2003), as

well as fewer depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults (Echeverría et al., 2008; Kim, 2010).

An important strand of research in this area examines the extent to which the neighborhood context structures older adults’ access to social relationships, social capital, and social support. Research on aging and the life course has drawn attention to aging-related changes in social connectedness, stemming in part from changes in daily experiences, capacities for maintaining ties, and the need for support, particularly due to bereavement or health decline (Charles and Carstensen, 2010; Wellman and Wortley, 1990). Social connections, services, and resources available in the neighborhood can help older adults compensate for network instability and loss. Differences in opportunities for social connectedness across neighborhoods may contribute to disparities in the ability to form and maintain social ties with family members and friends (York Cornwell and Behler, 2015). These, in turn, may be crucial determinants of independent living, life satisfaction, and health trajectories.

Coping with environmental challenges, particularly in a resource-poor environment, may sap time and energy, thereby depleting individuals’ abilities to maintain social ties, which may negatively impact health. Indeed, older adults who reside in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods appear to have smaller social networks. And older men who reside in such neighborhoods have been found to have less frequent social interaction with their network members (York Cornwell and Behler, 2015). An important alternative theory is that concentrated socioeconomic disadvantage may lead to the cultivation of social ties, including those with family members, friends, neighbors, and fictive kin (Stack, 1974). Long-term residents and women tend to take particularly active roles in exchanging support with neighbors (Schieman, 2005; Stack, 1974), especially during later life (Newman, 2003). However, many empirical studies suggest that residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods have fewer local social ties, overall, than those who reside in more-advantaged neighborhoods (e.g., Tigges et al., 1998; Small, 2007). As a result, older adults who reside in more socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods may be less likely to benefit from localized social exchanges and support from neighbors, such as visiting, sharing advice, and doing favors, which can promote their physical health, mental health, and continued residence in the community (Mair et al., 2010; Shaw, 2005; Wethington and Kavey, 2000).

Local social integration may also be fostered by characteristics of the neighborhood and the presence of institutions. For example, buildings with front porches or stoops are associated with greater access to social support among older adults (Brown et al., 2009). Local institutions and venues may also provide opportunities to form and maintain social relationships. For older adults, local senior centers can be particularly critical sites for

cultivating social ties (Glass and Balfour, 2003). Nearby welfare and social service offices, health care clinics, child care centers, retail establishments, recreational venues, and churches often promote socializing and exchanges of support with local others (e.g., Klinenberg, 2002; Small, 2009).

Neighborhood conditions may also determine whether an older adult is able to meet his or her daily needs, find satisfaction in daily life, and maintain independent residence in the community. Neighborhood context plays a critical role in the feasibility of everyday activities such as food shopping, household errands, or church attendance. In fact, physical activity is influenced by a variety of features of the neighborhood context, including the built environment, neighborhood-level social cohesion, and perceived safety (Tucker-Seeley et al., 2009). In a synthesis of over 120 articles, Yen et al. (2014) examined how place might shape physical mobility. They noted that three interrelated contexts—connectivity, land use, and aesthetics—are key drivers for whether older adults engage in outdoor space. Importantly, the key mechanism appears to be the perception of safety: not just a sense of whether the place seems safe but also more objective indicators such as speed limits, traffic lanes, and sidewalk quality.

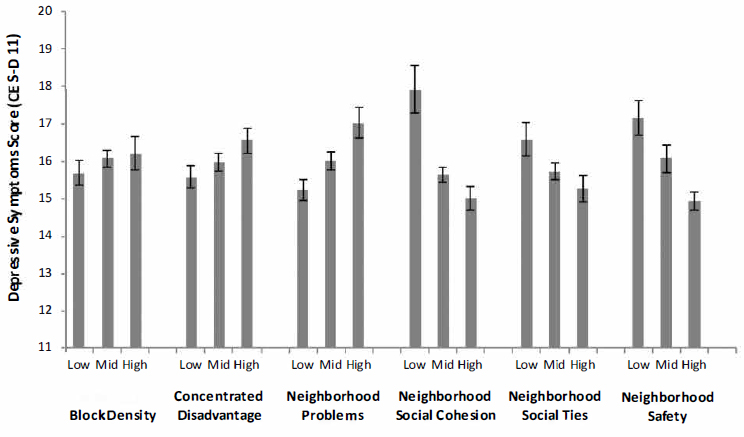

To examine the role of perceived safety and associated characteristics of the neighborhood, we analyzed data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) Wave 2 (2010–2011). Figure 5-3 illustrates the bivariate associations between neighborhood structural disadvantage, social context, and one aspect of health: depressive symptoms. Although depres-

SOURCE: Data from National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, Wave 2.

sive symptoms do not markedly vary across levels of neighborhood density, respondents who reside in neighborhoods with greater concentrated socioeconomic disadvantage and more neighborhood problems (e.g., buildings in disrepair, litter, odor, noise) had more depressive symptoms. Neighborhood social conditions, including cohesion, social ties, and safety, are negatively associated with depressive symptoms.

Activity Spaces

Research on neighborhood effects on health is primarily focused on the residential neighborhood, with little attention devoted to the other spaces that individuals encounter during their daily lives (Chaix, 2009; Diez-Roux, 2007; Matthews and Yang, 2013). Some scholars have suggested that focusing on the residential neighborhood is particularly appropriate when studying older adults, as age-related changes may reduce the geographic range of activities, increasingly anchoring daily life to the local, residential area (Inagami et al., 2007). But the assumption of shrinking turf in later life has not been empirically tested. Moreover, retirement may bring greater flexibility in structuring daily life, and older adults may move beyond their local neighborhood to access services, organizations, and amenities, as well as for social contact and participation in social activities (Cagney et al., 2013; York Cornwell and Cagney, 2017).

The notion of activity spaces—a concept stemming from research in geography—provides an alternative to the focus on residential neighborhoods (Golledge and Stimson, 1997). Activity spaces encompass the social environments that individuals encounter during their routine activities in everyday life (Browning and Soller, 2014; Cagney et al., 2013). Accordingly, activity spaces include, but are not limited to, residential neighborhoods.

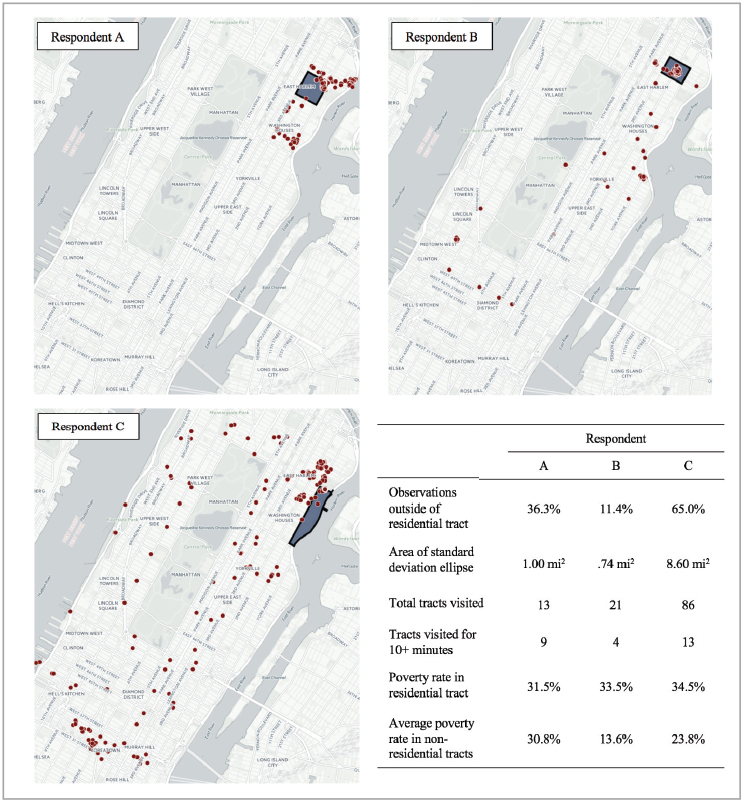

The span and characteristics of activity spaces vary across individuals. For example, Figure 5-4 summarizes the activity spaces of three older adults from East Harlem in New York City, using data from a smartphone-based study that included location tracking in 5-minute intervals for 7 days (see York Cornwell and Cagney, 2017). Note that time spent outside of the residential census tract varies widely across individuals—from 36 to 65 percent. Respondents A and B stay relatively close to their residential tracts for their daily activities, as indicated by the small size of their standard deviation ellipses (i.e., a geographic measure of the space that encompasses about 68 percent of the respondents’ observed locations) and the number of tracts they visited. Respondent C travels much further out into the city, encountering 86 different tracts during the course of the week. There is also heterogeneity in the characteristics of activity spaces where older adults spend their time. As shown here, Respondent A’s exposure to poverty outside of her census tract is similar to that within her residential tract. However,

NOTES: Dots represent respondents’ locations captured during the study; residential tracts are shaded in dark gray.

SOURCE: Originally published in York Cornwell, E., and Cagney, K.A. (2017). Aging in activity space: Results from smartphone-based GPS-tracking of urban seniors. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 72, 864–875. Oxford University Press.

both Respondents B and C are exposed to lower poverty outside of their census tracts than within their census tracts. B tends to visit particularly low-poverty tracts, but he spends much less time in these tracts than A or C.

Residential neighborhood contexts, adjoining areas, and the availability of public transportation may also contribute to across-neighborhood dif-

ferences in the extent to which individuals’ daily lives are locally focused (Rainham et al., 2010). Even more important for research on place and health in later life is the possibility that variation in the space, span, and characteristics of activity spaces may contribute to within-neighborhood variation in older adults’ health and well-being. That is, some older adults may be able to overcome limited local resources by accessing health care centers, pharmacies, and fresh food stores outside of their residential areas. Access to extra local resources may be influenced by individual characteristics, such as socioeconomic resources, social connectedness, health, and physical function (York Cornwell and Cagney, 2017; Kwan, 1999; Jones and Pebley, 2014). Or, access may be realized because such resources are located in areas that an individual frequently visits for other reasons, such as work, attending religious services, or making social visits (Kwan, 1999). Other older adults may be more tightly tethered to their residential areas, rendering physical and social features of the local residential context particularly salient.

MACRO-LEVEL EFFECTS OF AGING IN PLACE

Migration

Residential moves are not uncommon at later stages of the life course, and health status may be central to decisions about relocation. Older adults may migrate from another state, nation, or neighborhood; all such moves involve some form of relocation and all may be shaped by a variety of push and pull factors. Classical demographic theory suggests attention to migration patterns in any study of context (Longino, 1994), and this may be particularly salient for understanding the interplay of place, aging, and health. Although aging in place may reflect individual-level tastes to maintain residence in the community where one spent the bulk of his or her adult life, some communities might not be conducive to older adult needs, creating an incentive to relocate. As described earlier, housing structures typical to, for instance, suburban environments might not be suitable for older adults with mobility concerns or compromised health status.

At older ages, residential mobility is more prevalent among those who are retired, younger rather than older, with higher levels of income and wealth, poorer health, and urban dwelling (Sergeant and Ekerdt, 2008; Taylor et al., 2008; Walters, 2002). Poor weather and high tax rates may also be drivers of relocation (Walters, 2002). The literature on residential relocation related to children is sparse, but some evidence indicates that parents may make choices to move nearer adult children (Sergeant and Ekerdt, 2008).

In general, residential mobility drops after the age of 50; it continues to decline through the 1960s with a sharp uptick at approximately age 85.

Older adults who do make the choice to move disproportionately do so within their county or state. Approximately 14 percent move to another state, citing family reasons or retirement. Mobility rates for all age groups have fallen over the last two decades. Two-earner households and the long-term population shift to the south and west have reduced the later-life incentive to move (Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2014).

The structure of place shapes opportunity for movement. Recent research from the NSHAP suggests that when White older adults move, they move to communities at the same or a higher level of economic wellbeing. But when older African Americans move, they are more likely to relocate to communities at the same or lower economic levels (Riley et al., 2016). Consistent with this, Geronimus et al. (2014) found that African Americans are less likely to translate economic well-being into preferential moves. At the same time, patterns of residential mobility are themselves a structural property of place that may have consequences for community social context and individual outcomes. Residential instability may weaken neighborhood-level social cohesion (Sampson, 2012), but Cagney et al. (2005) found that when neighborhood-level affluence is low, residential stability is negatively related to individual health.

Our review of migration has focused primarily on voluntary moves, or moves that involve some agency on the part of the older adult. Involuntary moves are also a key component of migration patterns and are more prevalent among disadvantaged groups (Metzger et al., 2015). Residence in a disadvantaged neighborhood, for instance, increases mobility that stems from residential instability, such as eviction, or foreclosure, and poor housing conditions (Desmond and Shollenberger, 2015). Data suggest that such involuntary moves tend to be shorter in distance (Krysan and Crowder, 2017), but little is known about the consequences of involuntary moves for older adults’ access to social support or for their health trajectories.

Attention to migration and its drivers will be all the more important as the Baby Boom generation actively engages in retirement and other later life transitions that might suggest or require relocation. It remains unknown how this generation will respond to such changes or whether the physical and social environment will innovate in ways that can keep pace with their needs and facilitate aging in place.

Inequality

We have described the spaces that older adults inhabit, the spaces they may traverse, and the theory that may assist us in interpreting relevant findings. To what extent do those spaces contribute to durable inequality among important population subgroups?

Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in later-life health out-

comes, including chronic conditions, functional limitations, and mortality, are well documented in prior research and national health data (Pleis et al., 2010). However, individuals are embedded within communities, which expose them to sets of health-enhancing or heath-diminishing features that may exacerbate or ameliorate individual-level disparities. Cagney et al. (2005), for instance, found that neighborhood-level affluence attenuates the association between race and self-rated health. And Currie and Schwandt (2016), ranking counties by their poverty rates, found that among adults age 50 and over, mortality has declined more quickly in richer areas than in poorer ones; thus inequality in mortality has increased for older adults.

Metropolitan areas today are often characterized by deeply entrenched residential segregation, which generates differences in contextual exposure to health-related risks and resources (Sampson, 2012). As we noted above, physical and social characteristics of residential neighborhoods have been associated with a wide range of individual health outcomes. At the macro level, patterns of residential segregation may contribute to persistent disparities in health among older adults. Indeed, the spatial concentration of poverty or affluence is associated with health outcomes including mortality, even after adjusting for individuals’ own socioeconomic status (Pickett and Pearl, 2001; Wen et al., 2003). This suggests that inequalities in place play an important role in generating and maintaining socioeconomic inequalities in later-life morbidity and mortality.

Williams and Collins (2001) noted that spatial separation of racial groups should be considered a “fundamental cause of racial disparities in health” because it generates disproportionate exposure to social and physical risks that adversely affect the health of African Americans. For example, racially segregated neighborhoods often suffer from disinvestment of economic and municipal resources, so that these areas are more likely to lack services, including high-quality medical care, and they are more likely to have poorly maintained infrastructure such as sidewalks and street lights, and low housing quality (Williams and Rucker, 2000). Residence in segregated neighborhoods may bring heightened exposure to acute and chronic stressors, including experiences of criminal victimization (Shihadeh and Flynn, 1996) and forms of institutional and interpersonal discrimination that both characterize and perpetuate such segregation (Williams and Collins, 2001). These stressors exact wear and tear on the body that contribute to a process of “weathering,” leading to gradual health deterioration among Blacks. Exposure to segregated and discriminatory contexts over the life course is thought to result in racial disparities in chronic illness and disability that widen through middle age and into later life (Geronimus et al., 2006).

Exposure to green space, and the natural world more generally, varies not only by rural versus urban context but by microenvironments such as

neighborhoods. Architects and urban planners have long considered the role of the natural world in the health and well-being of the population, but attention to it within the health literature is relatively recent. In the mid-1980s, Ulrich (1984) observed that hospital length of stay was shorter for patients who could see trees outside their windows, as compared to brick walls. This work seeded interest in the relationship between exposure to nature and health outcomes. Mitchell and Popham (2008), for instance, found that income-based health inequalities in both all-cause mortality and mortality related to circulatory diseases were lower in populations living in the greenest spaces. Berman et al. (2012) explored whether walking in nature may be beneficial for individuals with major depressive disorder, finding that participants exhibited significant increases in memory span after walking in nature as compared to an urban space. In related work, Berman and colleagues (Kardan et al., 2015) found that residents who live in areas with a greater number of trees report better health and fewer cardio-metabolic conditions as compared to those living in areas with lower numbers. Analyses of green space and its density suggest important differences by sociodemographic composition. Wen et al. (2013) found that poverty was negatively associated with distances to parks and percentages of green spaces in urban and suburban areas while positively associated in rural areas. In general, percentages of Blacks and Hispanics were negatively associated with distances to parks and green space coverage.

NEW DIRECTIONS

It is an exciting time in the social sciences, and in research on aging specifically, to attend to the role of place in health. As we have described, place—through its physical attributes, physical resources, and constraints and through its interplay with the social contact that may emerge—is critical to examine if we are to fully understand how health and disease manifest themselves in the lives of older adults. Individual characteristics are clearly predictive of health status in later life (Case and Deaton, 2015), but evidence suggests that the context in which individuals are situated shapes those influences. A focus on place may allow us to activate aspects of place that might be health enhancing, enabling individuals and communities to effectively engage resources that can help older adults flourish.

We laid out environmental and geographical gerontology as important contributors to the assessment of place, and we highlighted the role of historic and contemporary research in urban sociology and related disciplines that have had an impact on research related to age. While these all have different origins and emphases, they share a focus on the interplay between the person and his or her environmental context. We see these approaches as complementary rather than competing; they each bring novel insights to an examination of place, aging, and health.

We suggest five general considerations for advancing the field. First, exploration of place as a set of nested contexts is in keeping with a synthetic view of the background work we describe above. Urban and rural areas are nested within regional, state, and national contexts, which may have important implications for the extent to which services availability varies across the density of settlements. State-level policies and investments in the provision of home- and community-based services, for example, may reduce disadvantages faced by rural seniors (Coburn et al., 2017), while at the same time increasing rural seniors’ engagement with their local contexts. We know very little about how residents perceive or experience “neighborhoods” outside of metropolitan areas, because research on neighborhood effects is primarily focused on urban areas (Burke et al., 2006; York Cornwell and Cagney, 2017). However, there is reason to believe that neighborhood effects on health and well-being vary across urban, suburban, and rural settings. For example, greater distance to health care and other services may make local social ties and support particularly important for nonmetropolitan older adults. The effects of local exposure to stressors may also be conditioned by one’s location in urban, suburban, or rural settings. Recent work suggests that racial gaps in exposure to neighborhood problems are growing fastest outside of urban areas (York Cornwell and Hall, 2017) and that exposure to disorder may be particularly isolating for seniors who reside outside of the city (York Cornwell and Behler, 2015).

Second, we believe that new forms of data will allow for a better understanding of the role of place in the lives of older adults. New data (potentially described as “big data”) allow for an unprecedented exploration of context (e.g., Gebru et al., 2017). We have already described “activity spaces” and the extent to which new technology facilitates their description in the moment and over time. Data such as these, and newly available sources that now can be readily linked to other data sources (e.g., crime, potholes, rat sightings) provide the opportunity to contextualize lives in a manner unknown just a few years ago. These novel data sources then allow us to husband social survey resources, since many of these data supplant respondent reports (e.g., hospital length of stay, procedures). We then can focus on what social surveys do best, which is to solicit opinions, preferences, and perspectives about the social world.

Third, we need to pay greater attention to how communities form and the barriers and inducements to residential sorting. One form of sorting is based on age, and evidence suggests that our communities are increasingly age segregated (Hagestad and Uhlenberg, 2005). What is the role of propinquity, and how might we theorize about the nature and extent of intergenerational exchange? Recent research suggests that the age composition of a community also may matter for health. Friedman et al. (2017) found that living in a neighborhood with a greater percentage of older adults is

related to better individual cognition at baseline but is not associated with decline. Perceived cohesion and disorder may explain some of the association between age structure and cognition. We believe that greater attention to age structure and the extent to which it varies—by communities, states, and nation—will benefit our understanding of the role of place in health.

Fourth, we acknowledge that this chapter did not consider virtual places and the extent to which some forms of contact via technology may substitute for the forms of interaction typically provided in proximity. Recent evidence suggests that the use of communication technologies is positively associated with formal and informal social participation (Kim et al., 2017). However, devices (e.g., monitors) that facilitate independent living for many older adults may substitute for interpersonal interaction and reduce the need for local social support. Detailed consideration of this literature is beyond the scope of this chapter, but this area is particularly relevant for future research on aging in place.

Finally, we believe that foundational and well-developed theory matters. We have emphasized theory in urban sociology in part because it arguably has received the greatest vetting and engagement. It suggests that the relevant space to be considered should be based on theory. We encourage researchers to incorporate a model that describes the characteristics of the place they are examining and what they imagine that place confers physically and socially. Theory on context needs to be employed at all levels, and theory that may be invoked to describe implications of policy change at the state level, for instance, will likely be inadequate or poorly suited for smaller spaces such as the neighborhood. Moreover, neighborhood-based theory, rich in its sociological history, may fail to fully capture the political influences that manifest at various municipal levels. As Lawton and colleagues called for near the end of his career (e.g., Parmelee and Lawton, 1990), careful consideration of the role of place is critical for understanding the dynamic processes of health and aging. We suggest that our understanding of the role of place in aging is at a turning point, where new theory and new data can be brought to bear on important questions related to health, well-being, and longevity.

REFERENCES

Andrews, G.J., Cutchin, M., McCracken, K., Phillips, D.R., and Wiles, J. (2007). Geographical gerontology: The constitution of a discipline. Social Science & Medicine, 65(1), 151–168.

Andrews, G.J., Evans, J., and Wiles, J.L. (2013). Re-spacing and re-placing gerontology: Relationality and affect. Aging and Society, 33(8), 1339–1373.

Berman, M.G., Kross, E., Krpan, K.M., Askren, M.K., Burson, A., Deldin, P., Kaplan, S., Sherdell, L., Gotlib, I.H., and Jonides, J. (2012). Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect in depressed individuals. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140(3), 300–305.

Besel, K., and Andreescu, V. (2013). Back to the Future: New Urbanism and the Rise of Neo-traditionalism in Urban Planning. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Birren, J.E. (1999). Theories of aging: A personal perspective. In V.L. Bengtson and K. Warner Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Aging (pp. 459-472). New York: Springer.

Brown, S.C., Mason, C.A., Lombard, J.L., Martinez, F., Plater-Zyberk, E., Spokane, A.R., Newman, F.L., Pantin, H., and Szapocznik, J. (2009). The relationship of built environment to perceived social support and psychological distress in Hispanic elders: The role of “eyes on the street.” Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 64(B), 234–246.

Browning, C.R., and Soller, B. (2014). Moving beyond neighborhood: Activity spaces and ecological networks as contexts for youth development. Cityscape, 16, 165–196.

Browning, C.R., Cagney, K.A., and Morris, K. (2014). Early Chicago School theory. In G. Bruinsma and D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (pp. 1233–1242). New York: Springer.

Buckwalter, K.C., and Davis, L.L. (2011). Elder caregiving in rural communities. In R. Talley, K. Chwalisz, and K. Buckwalter (Eds.), Rural Caregiving in the United States: Research, Practice, Policy (pp. 33–46). New York: Springer.

Burke, J.G., O’Campo, P., and Peak, G.L. (2006). Neighborhood influences and intimate partner violence: Does geographic setting matter? Journal of Urban Health, 83, 182–194.

Cagney, K.A., and Browning, C.R. (2004). Exploring neighborhood-level variation in asthma and other respiratory diseases. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19, 229–236.

Cagney, K.A., and York Cornwell, E. (2010). Neighborhoods and health in later life: The intersection of biology and community. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 30, 323–348.

Cagney, K.A., Browning, C.R., and Wen, M. (2005). Racial disparities in self-rated health at older ages: What difference does the neighborhood make? Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 60(4), S181–S190.

Cagney, K.A., Browning, C.R., Jackson, A.L., and Soller, B. (2013). Networks, neighborhoods, and institutions: An integrated “activity space” approach for research on aging. In L. Waite (Ed.), New Directions in the Sociology of Aging (pp. 151–174). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Caldwell, J.T., Ford, C.L., Wallace, S.P., Wang, M.C., and Takahashi, L.M. (2016). Intersection of living in a rural versus urban area and race/ethnicity in explaining access to health care in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1463–1469.

Cannuscio, C., Block, J., and Kawachi, I. (2003). Social capital and successful aging: The role of senior housing. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139(5 Part 2), 395–399.

Canter, D.V., and Craik, K.H. (1981). Environmental psychology. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 1(1), 1–11.

Case, A., and Deaton, A. (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among White non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112, 15078–15083.

Chaix, B. (2009). Geographic life environments and coronary heart disease: A literature review, theoretical contributions, methodological updates, and a research agenda. Annual Review of Public Health, 30, 81–105.

Charles, S.T., and Carstensen, L.L. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383–409.

Coburn, A.F., Lundblad, J.P., and the RUPRI Health Panel. (2017). Rural Long-Term Services and Supports: A Primer. Iowa City: Rural Policy Research Institute.

Currie, J., and Schwandt, H. (2016). Inequality in mortality decreased among the young while increasing for older adults, 1990–2010. Science, 352(6286), 708–712.

Curtis White, K.J., and Guest, A.M. (2003). Community lost or transformed? Urbanization and social ties. City & Community, 2, 239–259.

Cutchin, M.P. (2009). Geographical gerontology: New contributions and spaces for development. Gerontologist, 49(3), 440–444.

Desmond, M., and Shollenberger, T. (2015). Forced displacement from rental housing: Prevalence and neighborhood consequences. Demography, 52(5), 1751–1772.

Diez-Roux, A.V. (2007). Neighborhoods and health: Where are we and where do we go from here? Revue D’epidemiologie et de Sante Publique, 55, 13–21.

Diez-Roux, A.V., Merkin, S.S., Arnett, D., Chambless, L., Massing, M., Nieto, F.J., Sorlie, P., Szklo, M., Tyroler, H.A., and Watson, R.L. (2001). Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 345, 99–106.

Echeverría, S.E., Diez-Roux, A.V., Shea, S., Borell, L.N., and Jackson, S. (2008). Associations of neighborhood problems and neighborhood social cohesion with mental health and health behaviors: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Health & Place, 14, 853–865.

Fishman, T.C. (2010). Shock of Gray. New York: Scribner.

Friedman, E.M., Shih, R.A., Slaughter, M.E., Weden, M.M., and Cagney, K.A. (2017). Neighborhood age structure and cognitive function in a nationally-representative sample of older adults in the U.S. Social Science and Medicine, (174), 149–158.

Gebru, T., Krause, J., Wang, Y., Chen. D., Deng, J., Aiden, E.L., and Fei-Fei, L. (2017). Using deep learning and Google Street View to estimate the demographic makeup of neighborhoods across the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114, 13108–13133.

Geronimus, A.T., Hicken, M., Keene, D., and Bound, J. (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826–833.

Geronimus, A.T., Bound, J., and Ro, A. (2014). Residential mobility across local areas in the United States and the geographic distribution of the healthy population. Demography, 51(3), 777–809.

Glasgow, N., and Brown, D.L. (2012). Rural ageing in the United States: Trends and contexts. Journal of Rural Studies, 28(4), 422–431.

Glass, T.A., and Balfour, J.L. (2003). Neighborhoods, aging, and functional limitations. In I. Kawachi and L.F. Berkman (Eds.), Neighborhoods and Health (pp. 303–334). New York: Oxford University Press.

Golant, S.M. (1972). The Residential Location and Spatial Behavior of the Elderly: A Canadian Example (Research Paper No. 143). Chicago: University of Chicago, Department of Geography.

Golant, S.M. (1975). Residential concentrations of the future elderly. Gerontologist, 15(1 Part 2), 16–23.

Golant, S.M. (2009). Aging in place solutions for older Americans: Groupthink responses not always in their best interests. Public Policy & Aging Report, 19(1).

Golledge, R.G., and Stimson, R.J. (1997). Spatial Behavior: A Geographic Perspective. New York: Guilford Press.

Hagestad, G.O., and Uhlenberg, P. (2005). The social separation of old and young: A root of ageism. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 343–360.

Hand, C.L., and Howrey, B.T. (2017). Associations among neighborhood characteristics, mobility limitation, and social participation in late life. Journals of Gerontology: Series B. doi. 10.1093/geronb/gbw215. E-pub ahead of print.

Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. (2014). Housing America’s Older Adults: Meeting the Needs of an Aging Population. Available: http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research/publications/housing-americas-older-adults%E2%80%94meeting-needs-aging-population [April 2018].

Hawkley, L.C., Thisted, R.A., Masi, C.M., and Cacioppo, J.T. (2010). Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 25(1), 132–141.

Hofferth, S.L., and Iceland, J. (1998). Social capital in rural and urban communities. Rural Sociology, 63(4), 574–598.

Hogan, M.J., Leyden, K.M., Conway, R., Goldberg, A., Walsh, D., and McKenna-Plumley, P.E. (2016). Happiness and health across the lifespan in five major cities: The impact of place and government performance. Social Science & Medicine, 162, 168–176.

Inagami, S., Cohen, D.A., and Finch, B.K. (2007). Non-residential neighborhood exposures suppress neighborhood effects on self-rated health. Social Science & Medicine, 65, 1779–1791.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage.

Jirik, S., and Sanders, S. (2014). Analysis of elder abuse statutes across the United States, 2011–2012. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57(5), 478–497.

Jones, M., and Pebley, A. (2014). Redefining neighborhoods using common destinations: Social characteristics of activity spaces and home census tracts compared. Demography, 51(3), 727–752.

Kardan, O., Gozdyra, P., Misic, B., Moola, F., Palmer, L.J., Paus, T., and Berman, M.G. (2015). Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center. Scientific Reports, 5, 11610.

Kawachi, I., and Berkman, L.F. (2003). Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In L. Berkman and I. Kawachi (Eds.), Social Epidemiology (pp. 303–334). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kim, J. (2010). Neighborhood disadvantage and mental health: The role of neighborhood disorder and social relationships. Social Science Research, 39, 260–271.

Kim, J., Lee, H.Y., Christensen, M.C., and Merighi, J.R. (2017). Technology access and use, and their associations with social engagement among older adults: Do women and men differ? Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 72, 836–845.

King, A.C., Sallis, J.F., Frank, L.D., Saelens, B.E., Cain, K., Conway, T.L., Chapman, J.E., Ahn, D.K., and Kerr, J. (2011). Aging in neighborhoods differing in walkability and income: Associations with physical activity and obesity in older adults. Social Science & Medicine, 73(10), 1525–1533.

Klinenberg, E. (2002). Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Krysan, M., and Crowder, K. (2017). The Cycle of Segregation: The Perpetuation of Residential Stratification in Metropolitan America. New York: Russell Sage.

Kwan, M.-P. (1999). Gender and individual access to urban opportunities: A study using space-time measures. Professional Geographer, 51, 210–227.

Latham, K., Clarke, P., and Pavela, G. (2015). Social relationships, gender, and recovery from mobility limitation among older Americans. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences, 70(5), 769–781.

Lawton, M.P., and Nahemow, L. (1973). Ecology and the aging process. In C. Eisdorfer and M.P. Lawton (Eds.), The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging (pp. 619–674). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Longino, C.F. (1994). Where retirees prefer to live: The geographical distribution and migratory patterns of retirees. In A. Monk (Ed.), The Handbook of Retirement (pp. 405–416). New York: Columbia University Press.

Mair, C., Diez Roux, A.V., and Morenoff, J. (2010). Neighborhood stressors and social support as predictors of depressive symptoms in the Chicago Community Adult Health Study. Health & Place, 116, 811–819.

Matthews, S.A., and Yang, T.-C. (2013). Spatial Polygamy and Contextual Exposures (SPACEs): Promoting activity space approaches in research on place and health. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 1057–1081.

McCarthy, L., and Kim, S. (2005). The Aging Baby Boomers: Current and Future Metropolitan Distributions and Housing Policy Implications. Office of Policy Development and Research. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Metzger, M.W., Fowler, P.J., Anderson, C.L., and Lindsay, C.A. (2015). Residential mobility during adolescence: Do even “upward” moves predict dropout risk? Social Science Research, 53, 218–223.

Mitchell, R., and Popham, F. (2008). Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: An observational population study. Lancet, 372(9650), 1655–1660.

Montez, J.K., Zajacova, A., and Hayward, M.D. (2017a). Disparities in disability by educational attainment across U.S. states. American Journal of Public Health, 107(7), 1101–1108.

Montez, J.K., Hayward, M.D., and Wolf, D.A. (2017b). Do U.S. states’ socioeconomic and policy contexts shape adult disability? Social Science & Medicine, 178, 115–126.

Moore, K.D. (2014). An ecological framework of place: Situating environmental gerontology within a life course perspective. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 79(3), 183–209.

Newman, K.S. (2003). A Different Shade of Gray: Midlife and Beyond in the Inner City. New York: The New Press.

North, M.S., and Fiske, S.T. (2015). Modern attitudes toward older adults in the aging world: A cross-cultural meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(5), 993–1021.

Parmelee, P.A., and Lawton, M.P. (1990). Design of special environments for the elderly. In J.E. Birren and K.W. Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of Psychology and Aging, 3rd ed. (pp. 464–487). New York: Academic Press.

Pendall, R., Goodman, L., Zhu, J., and Gold, A. (2016). The Future of Rural Housing. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Pickett, K.E., and Pearl, M. (2001). Multilevel analysis of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: A critical review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55, 111–122.

Pleis, J.R., Ward, B.W., and Lucas, J.W. (2010). Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Vital Health Statistics, 10, 1–207.

Rainham, D., McDowell, I., Krewski, D., and Sawada, M. (2010). Conceptualizing the health-scape: Contributions from time geography, location technologies and spatial ecology to place and health research. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 668–676.

Reinhard, S., Kassner, E., Hendrickson, L., and Mollica, R. (2012). State Long-Term Services and Supports Scorecard: What Distinguishes High- from Low-Ranking States? Overview of Three Case Studies. Washington, DC: AARP.

Riley, A., Hawkley, L.C., and Cagney, K.A. (2016). Racial differences in the effects of neighborhood disadvantage on residential mobility in later life. Journals of Gerontology Series B, 71, 1131–1140.

Robert, S.A., and Li, L.W. (2001). Age variation in the relationship between community socioeconomic status and adult health. Research on Aging, 23, 233–258.

Rowles, G.D. (1981). The surveillance zone as meaningful space for the aged. Gerontologist, 21(3), 304–311.

Sampson, R.J. (2012). Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, R.J., and Groves, B.W. (1989). Community structure and crime: Testing social disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 774–802.

Sampson, R.J., Raudenbush, S.W., and Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 227, 918–923.

Schieman, S. (2005). Residential stability and the social impact of neighborhood disadvantage: A study of gender- and race-contingent effects. Social Forces, 83, 1031–1064.

Sergeant, J.F., and Ekerdt, D.J. (2008). Motives for residential mobility in later life: Post-move perspectives of elders and family members. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 66, 131–154.

Shaw, B.A. (2005). Anticipated support from neighbors and physical functioning during later life. Research on Aging, 27, 503–525.

Shaw, J., Farid, M., and Noel-Miller, C. (2017). Social isolation and medicare spending: Among older adults, objective isolation increases expenditures while loneliness does not. Journal of Aging and Health, 29, 1119–1143.

Shihadeh, E.S. and Flynn, N. (1996). Segregation and crime: The effect of black social isolation on the rates of black urban violence, Social Forces, 74(4), 1325–1352.

Shiode, N., Morita, M., Shiode, S., and Okunuki, K. (2014). Urban and rural geographies of aging: A local spatial correlation analysis of aging population measures. Urban Geography, 35(4), 608–628.

Simmel, G. (1903). Metropolis and mental life. Reprinted in D.N. Levine (Ed.), On Individuality and Social Forms (1971, pp. 324–339). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Singh, G.K., and Siahpush, M. (2014). Widening rural–urban disparities in life expectancy, U.S., 1969–2009. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(2), 19–29.

Skinner, M.W., Andrews, G.J., and Cutchin, M.P. (Eds.). (2017). Geographical Gerontology: Perspectives, Concepts, Approaches. Abington, UK: Routledge.

Small, M. (2007). Racial differences in networks: Do neighborhood conditions matter? Social Science Quarterly, 88, 320–343.

Small, M. (2009). Unanticipated Gains: Origins of Network Inequality in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Smith, P. (2014). A historical perspective in aging and gerontology. In H. Vakalahi, G. Simpson, and N. Giunta (Eds.), The Collective Spirit of Aging Across Cultures (International Perspectives on Aging, 9, pp. 7–27). Dordrecht: Springer.

Stack, C. (1974). All Our Kin: Strategies for Survival in a Black Community. New York: Basic Books.

Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., and Stone, A.A. (2015). Subjective well-being, health, and ageing. Lancet, 385, 640–648.

Subramanian, S.V., Chen, J.T., Rehkopf, D.H., Waterman, P.D., and Krieger, N. (2005). Racial disparities in context: A multilevel analysis of neighborhood variations in poverty and excess mortality among Black populations in Massachusetts. American Journal of Public Health, 95(2), 260–265.

Subramanian, S.V, Kubzansky, L., Berkman, L., Fay, M., and Kawachi, I. (2006). Neighborhood effects on the self-rated health of elders: Uncovering the relative importance of structural and service-related neighborhood environments. Journals of Gerontology Series B, 61(3), S153–S160.

Taylor, P., Morin, R., Cohn, D., and Wang, W. (2008). American Mobility: Who Moves? Who Stays Put? Where’s Home? Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Tigges, L.M., Browne, I., and Green, G. (1998). Social isolation of the urban poor: Race, class, and neighborhood effects on social resources. Sociological Quarterly, 39, 53–77.

Tucker-Seeley, R., Subramanian, S.V., Li, Y., and Sorensen, G. (2009). Neighborhood safety, socioeconomic status, and physical activity in older adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(3), 207–213.

Ulrich, R.S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420–421.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). The Nation’s Older Population Is Still Growing (Census Bureau Reports, Release No. CB17-100). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Vasunilashorn, S., Steinman, B.A., Liebig, P.S., and Pynoos, J. (2012). Aging in place: Evolution of a research topic whose time has come. Journal of Aging Research, 2012, 1–6. doi: 10.1155/2012/120952.

Wahl, H.-W., and Weisman, G.D. (2003). Environmental gerontology at the beginning of the new millennium: Reflections on its historical, empirical, and theoretical development. Gerontologist, 43(5), 616–627.

Walters, W.H. (2002). Later-life migration in the United States: A review of recent research. Journal of Planning Literature, 17(1), 38–66.

Wellman, B., and Wortley, S. (1990). Different strokes from different folks: Community ties and social support. American Journal of Sociology, 96(3), 558–588.

Wen, M., Browning, C.R., and Cagney, K.A. (2003). Poverty, affluence, and income inequality: Neighborhood economic structure and its implications for health. Social Science & Medicine, 57, 843–860.

Wen, M., Zhang, X., Harris. C.D., Holt, J.B., and Croft, J.B. (2013). Spatial disparities in the distribution of parks and green spaces in the U.S. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 45(S1), 18–27.

Wethington, E., and Kavey, A. (2000). Neighboring as a form of social integration and support. In K. Pillemer, P. Moen, E. Wethington, and N. Glasgow (Eds.), Social Integration in the Second Half of Life (pp. 190–210). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wight, R.G., Aneshensel, C.S., Miller-Martinez, D., Botticello, A.L., Cummings, J.R., Karlamangla, A.S., and Seeman, T.E. (2006). Urban neighborhood context, educational attainment, and cognitive function among older adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 163(12), 1071–1078.

Williams, D.R., and Collins, C. (2001). Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports, 116, 404–416.

Williams, D.R., and Rucker, T.D. (2000). Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health Care Financing Review, 21, 75–90.

Wilson, W.J. (1987). The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Winterton, R. (2017). Therapeutic landscapes of ageing. In M.W. Skinner, M.P. Cutchin, and G.J. Andrews (Eds.), Geographical Gerontology: Perspectives, Concepts, Approaches (pp. 293–304). London: Routledge.

Wirth, L. (1938). Urbanism as a way of life. American Journal of Sociology, 44(1), 1–24.

Yen, I.H., Flood, J.F., Thompson, H., Anderson, L.A., and Wong, G. (2017). How design of places promotes or inhibits mobility of older adults: Realist synthesis of 20 years of research. Journal of Aging and Health, 26(8), 1340–1372.

York Cornwell, E., and Behler, R.L. (2015). Urbanism, neighborhood context, and social networks. City & Community, 14, 311–335.

York Cornwell, E., and Cagney, K.A. (2017). Aging in activity space: Results from smartphone-based GPS tracking of urban seniors. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 72(5), 864–875.

York Cornwell, E., and Currit, A. (2016). Racial and social disparities in bystander support during medical emergencies on U.S. streets. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 1049–1051.

York Cornwell, E., and Hall, M. (2017). Neighborhood problems across the rural-urban continuum: Geographic trends and racial and ethnic disparities. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 672, 238–256.

This page intentionally left blank.