15

Payments for Value Over Volume

INTRODUCTION

The current fee-for-service system has been criticized as one that rewards the delivery of volume of services over the delivery of effective care. Discussions of options to reform the payment system to align payments with value have ranged from bundled payments for acute care episodes to accountable care organizations and gainsharing.1 Presenters in this session explored current and past experiments with payment reform. While focusing specifically on bundled payments for providers, they revealed that although some practices are promising, there remain significant challenges for implementation.

John M. Bertko of the Brookings Institution and Linda M. Magno of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) opened this session by describing bundled payment initiatives and discussing their successes and limitations. Bertko applauds the successes of bundled payments in systems such as the Geisinger Health System but explains that bundled payments may not work in all cases. While this payment structure has succeeded in improving quality and lowering costs in Pennsylvania, the payment bundles pertain to very discrete and easily definable conditions, such as coronary artery bypass graft surgeries. Furthermore, he states that, while bundled payments have worked well in integrated healthcare systems, the issue of replicability within the non-integrated delivery system that currently

dominates the national landscape remains. Magno echoes Bertko’s thoughts in reviewing the work of CMS in launching demonstration projects on bundled payments. Among the lessons that Magno shared from these experiences are the need to bundle strategically because savings are most likely to be realized from targeting complex, high-cost inpatient procedures that involve significant but standardized services. Furthermore, she describes how bundled payments can realign service and utilization incentives and lead to savings beyond the discounted rates of the bundles.

Shifting the focus to physician engagement, George J. Isham of Health-Partners offers some thoughts on building support among physicians and other practitioners based on his experiences in Minnesota. He indicates that current reform efforts have been layered on top of existing delivery systems where care is fragmented, administration is manual, and fee for service still characterizes the majority of payment. Isham specifically discusses the significant time and resource needs for designing and implementing bundles. He further states that physicians need to be involved in the design of bundles and require support during implementation. Based on these lessons, he offers several concrete policy recommendations that include supporting more pilots of bundled payment systems; providing technical assistance for providers in managing these systems and in improving quality; and developing a national strategy for overall delivery system reform that includes support for bundled payment systems.

Closing this session, Nancy Davenport-Ennis of the National Patient Advocate Foundation addresses the perspectives of patients in the discussion of bundled payments. Stressing the importance of including active patient engagement in decision making even in a new payment system, she raises the importance of educating patients about what these reforms mean for patients’ out-of-pocket expenses; where the cost savings are going to go; and how a new payment system would impact patient access to the latest developments in medical treatment.

BUNDLED PAYMENTS: A PRIVATE PAYER PERSPECTIVE

John M. Bertko, F.S.A., M.A.A.A.

The Brookings Institution

Bundled payments are proposed as one possible solution for changing the incentives in fee-for-service (FFS) payment systems. Ideally, bundled payments for hospitals and physicians would provide financial incentives to use appropriate levels and types of services and to increase care coordination. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), among other bodies, has investigated the potential use of bundled payments for the traditional Medicare program. Private insurers have experimented and used

some forms of bundled payments over the last 20 years, with both successes and failures. Successes include Geisinger Health System’s ProvenCare™ program under which hospital and physicians are paid a global fee and the bundled payment transplant programs that most insurers use. Failures include what were called (in the late 1990s) “contact capitation” and a somewhat similar approach by start-up firms. Although bundled payments for acute episodes offer promise of incentives for efficiency, there are still many unresolved questions about the scale of this promise and the practical mechanics of making it work with providers.

Private Payer Successes with Bundled Payments

Geisinger’s ProvenCare non-emergent coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) program has successfully introduced bundled payments and reengineered processes for its health insurance enrollees in its Pennsylvania marketplace. Results have been impressive, with increases in quality measure results and decreased costs. Following up on this program, Geisinger reportedly will expand the ProvenCare program to include more procedures, including emergent CABG, knee replacements, and cataract surgeries. The success of this program illustrates both the promise of bundled payments for a limited set of procedures and the work required to create the infrastructure needed for quality and efficiency.

In the ProvenCare model, hospitals and physicians are paid a global fee for pre- and postoperative care as well as for the inpatient procedure, giving the providers an incentive to reengineer their processes. Geisinger’s surgeons reviewed the literature and after months of study agreed upon 40 best-practice behaviors, including the following:

-

Pre-admission documentation of 12 items;

-

Eight items in operative documentation;

-

Ten items in postoperative documentation; and

-

Discharge and postdischarge processes.

Reports are that all patients received 100 percent of the processes within six months.

Transplant Networks

Most health insurers have transplant networks in place that involve bundled payments to centers of excellence for transplants. Not only are these facilities providing high-quality transplant services, they often do so at greatly reduced costs. The author’s experience indicates that cost can be reduced as much as 50 percent from those of transplant facilities that

are not within the network. Yet transplants are very high-cost procedures, frequently costing in excess of $100,000. Thus, the effort to organize and negotiate for these bundled arrangements is clearly worth the potential savings. Even with such a clearly defined procedure as a transplant, there are different phases that may be included in the bundle, including evaluation, pre-transplant, the transplant procedure, and the post-transplant period. The most comprehensive bundle would include all four phases, but not all insurers have all components in bundled payments with every facility in the preferred network.

Past Failures

Some efforts with bundled payments may have been too ambitious. In the 1990s, several consultants and some insurers tried what is sometimes called contact capitation. In this method, a specialist was paid a fixed amount each time a patient came in “contact.” Thus, the incidence risk was eliminated for providers while attempting to bundle the procedures associated with a specialty visit. There was not much take-up of this concept because some specialists were leery of accepting any risk, instead choosing to continue receiving FFS payments. A few other physicians were able to “game” the system by providing many low-cost procedures (e.g., hypertensive patient contacts by cardiologists) at the standard contact capitation rate, rather than focusing only on high-cost contacts.

Similarly, a few start-up firms in the 1990s attempted to have consumers purchase “shopping carts” of bundled episodes from likely specialists (such as obstetrics-gynecology deliveries, cardiology procedures) in a quasi-insured market. While this was an interesting concept, neither of the companies attempting to deliver this market of bundled services to consumers succeeded. This experiment occurred in an era of several “consumer-directed” health plan start-ups and was not carefully designed because this concept required partnership with a traditional insurer to hold the majority of the insurance risk. As a result, these entrepreneurs had a “product concept” without a practical foundation.

Are Providers Willing? “Plug and Socket” Metaphor

In constructing a strategy to promote bundling, an analyst must look at both the construction of the bundled payment and the receiver of the payment, much like one needs both a plug and socket to complete an electrical circuit. Many payers have the capability and data to calculate an appropriate payment, even with complex adjustments for severity levels, but will there be some organization ready to receive and use the payment? In most of the nation, hospitals are accustomed to receiving facility-only diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments, but most do not have formal contractual

arrangements with their specialty physicians (although employed primary care physicians are becoming more common). Similarly, if one were to pay a single- or multispecialty physician group a bundled payment for a complex procedure, would it have a contract to pay the hospital “partner” or would it be forced to pay the much higher price from the hospital’s retail fee schedule?

More Considerations

Another consideration is the patient. Do there need to be incentives (or penalties) to direct patients to use certain bundled providers, rather than any physician and any hospital? This might be practical for private payers, but there is limited flexibility with FFS Medicare.

Cadence

We are a nation in crisis, needing to find solutions to the immense problem of healthcare costs rising faster than the growth of gross domestic product (GDP). Bundled payments, if used carefully, offer one tactic among many to move toward a solution. In many ways, if there is increasing provider and beneficiary accountability (e.g., accountable care organizations with a budget to manage), bundled payments could be helpful.

A suggestion is that we have rapid development, piloting, and rollout of limited bundling tactics. Following the lead of Geisinger and other systems, it appears that a short list of certain well-defined acute conditions (e.g., emergent and non-emergent CABG, hip and knee replacements, cataract surgery, gastric bypass) could provide experience with some level of immediate savings while bundled payment strategies are developed to provide incentives for systems to get organized to receive these payments. Starting with a small number of Medicare-paid conditions, expansion could occur in two directions: Medicare could explore whether more conditions could be covered, and the private insurer world could be a “fast follower” of Medicare by contracting with organizations that already are able to handle the bundled payments for Medicare. Timewise, this could start with a handful of pilots (e.g., 5 to 10), expanded to 50 as soon as proven to have a successful format, and then to 500 to 1,000 within 5 years. The physicians and hospitals are in place; next, the appropriate contractual arrangements and organization are needed. Medicare would have to lead since both providers and insurers are reluctant to move off the profitable status quo and Medicare has the ability to offer (or even require) these arrangements through administrative pricing (consider the implementation of DRGs in the 1980s).

Virtual bundling is also a possibility—and could be the penalty—that makes the provider community move toward accepting a reasonable range

of bundled procedures. Many observers believe that virtual bundling in the absence of “real” delivery systems would be problematic, though.

Summary

Rapid adoption of a limited set of bundled procedures appears to be both possible and a good idea. Bundled payments for acute care episodes are practical and working today for a small number of procedures. We need to move forward quickly, but only for a narrow range of episodes that will clearly work.

Providers need to be willing to accept bundled payments and the associated risks. The financial and professional incentives from “fixing the system” have to be sufficient to convince these stakeholders that the large effort is worthwhile on a voluntary basis. Consumers may need to have insurance products redesigned to provide a financial incentive to choose a high-quality, efficient, bundled system (which could be called a “center of excellence”), rather than using the nearest hospital system and local surgeon. Individuals, families, and caregivers will need credible information to understand how and when to access these bundled centers of excellence.

MEDICARE AND BUNDLED PAYMENTS

Armen H. Thoumaian, Ph.D., Linda M. Magno, M.P.A., and Cynthia K. Mason, R.N., M.B.A.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

The common perception that “higher expenditures for more services and expensive procedures yield better quality and outcomes” does not necessarily reflect reality. In fact, the opposite is often true. Under the Medicare fee-for-service payment system, inpatient hospital and physician services are paid separately. Hospitals are paid for inpatient care on a per-discharge basis and therefore have an incentive to minimize services furnished to inpatients and to reduce lengths of stay. Conversely, physicians, paid on a fee-for-service basis, face no incentive to control hospital service utilization or to minimize costs of the hospital services they order. However, the incentives of physicians and hospitals are aligned insofar as hospitals are rewarded for increasing inpatient admissions, and there is no incentive for physicians to discourage unnecessary admissions and costly procedures.

The Bundled Payment Strategy

Bundled payment strategies that take advantage of competitive market forces have been considered a potential means for the Medicare program to lower the expense of high-volume, high-cost healthcare episodes. An all-

inclusive bundled payment strategy has the potential to realign payment incentives to improve quality of care and outcomes, reduce unnecessary costs, facilitate more efficient service delivery, and improve patient satisfaction without affecting the Medicare beneficiary’s freedom to choose providers.

The following is a description of some of the experiences of the Medicare program in conducting bundled payment demonstrations and what has been learned from the findings. The Medicare experience with bundled payments began early in 1988. Since the mid-1980s, numerous studies have found an inverse relationship between institutional volume and mortality for CABG surgery (Donabedian, 1984; Flood et al., 1984; Hughes et al., 1987; Luft et al., 1987; Showstack et al., 1987). A complementary analysis of Medicare claims data in the late 1980s showed that one-third of CABG surgeries took place at hospitals performing fewer than 50 Medicare cases per year (Health Care Financing Administration, 1992). During this same period there was a well-publicized initiative at the Texas Heart Institute (THI) at St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital in Houston, Texas. THI offered private insurers a negotiated bundled payment price for all physician services connected with an inpatient CABG admission that provided savings to the payer. Putting together the relationship between volume and quality and the cost savings that might be achieved from a bundled payment, an August 1987 Office of the Inspector General (OIG) report recommended the implementation of a Medicare demonstration to attempt to lower costs by arranging for an all-inclusive package price for CABG surgery with selected high-volume hospitals (Office of Inspector General, 1987). This recommendation was the catalyst that led to a number of Medicare bundled payment demonstrations.

The Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Center Demonstration

The Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Center Demonstration was designed and implemented to test the cost effectiveness of a bundled payment for CABG surgery. Despite the considerable financial risk to hospitals of adopting a bundled payment system, numerous hospitals applied to participate and 4 out of 10 finalist hospitals began the demonstration in May 1991 in Georgia, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Ohio. The demonstration was expanded to three more hospitals in 1993 and ended in June 1996. All-inclusive bundled payment packages were negotiated for CABG surgery with discounts from the hospitals ranging from 5 to 30 percent of the estimated Medicare Part A and Part B payments that would otherwise have been made to these hospitals for DRGs 106 and 107. The packages included all hospital and physician services, outliers, and readmissions occurring within a window of 3 days to 6 weeks from discharge.

The bundled payment realigned the payment incentives of both hospitals and physicians around the common goals of improving quality and

reducing cost. The resulting new cooperative relationship between the hospital and physicians led to innovative initiatives to achieve these goals. One such initiative was a provider incentive program later referred to as “gainsharing.” Hospital staff and physicians were rewarded with monetary bonuses for their contributions to improve quality and cut costs.

The bundled payment demonstration saved more than $50 million on 10,000 procedures performed at the seven hospitals, approximately $42 million for Medicare from the discounted payment and another $8 million to beneficiaries or Medigap insurers in the form of reduced coinsurance amounts. Findings suggested that the bundled payment methodology was instrumental in creating an incentive for both physicians and hospitals to work together to reduce costs. This led demonstration sites to identify opportunities for savings through changes in clinical management of patients that resulted in shorter lengths of stay, better management of pharmaceuticals, and standardization of equipment. Changes in treatment protocols reduced average costs in operating rooms, intensive care units, and routine nursing services, yielding further savings to hospitals. One of the most interesting findings was that post-acute care costs decreased by about $4.1 million in the demonstration sites owing to improved outcomes at discharge that reduced readmissions, home healthcare episodes, and outpatient visits. This demonstration showed that complex, inpatient procedures with a defined inpatient stay and significant but standardized resource use, may be good candidates for a bundled payment program to achieve substantial cost savings and quality improvement.

The Cataract Alternative Payment Demonstration

Cataract surgery was among the most frequent procedures performed in 1988, and there was reason to believe that costs were not declining commensurate with volume increases and technological advances. The Cataract Alternative Payment Demonstration was conducted from 1993 to 1996 to test the efficacy of a negotiated bundled payment to achieve a savings for Medicare while improving quality of care and outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries. Four participants in three cities began the demonstration: Cleveland, Ohio; Dallas, Texas; and Phoenix, Arizona. The bundled payment included all facility costs and physician fees, the cost of the intraocular lens, and all pre- and postoperative tests and follow-up visits. The discounts achieved ranged from 2 to 5 percent. The demonstration produced only about $500,000 in savings after 4,500 procedures. The limited number of resources involved in an individual case reduced opportunities for increasing efficiencies. Benefits to participating providers were further minimized by the fact that volume increases failed to materialize. The evaluation concluded that outpatient procedures involving few

professional staff, processes, and supplies may not be good candidates for bundled payment programs.

Participating Centers of Excellence Demonstration and Gainsharing

Building on the experiences from the CABG and cataract demonstrations, Medicare began in 1995 to develop another demonstration to test the bundled payment approach, the Participating Centers of Excellence Demonstration for Orthopedic and Cardiovascular Services, which was set to be implemented in 100 sites across 10 states. However, the demonstration was never implemented for a variety of reasons—most significantly, competing resources for implementation of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 and a moratorium on systems changes related to the year 2000. Subsequent efforts to implement the demonstration faced challenges resulting from changes in the underlying bundle of services for the cardiac DRGs and organized opposition from the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.

The gainsharing initiatives, however, which were based on the concept used successfully in the CABG demonstration, gained increasing interest as a less complex alternative to bundling. Medicare is currently testing this approach in 14 hospitals. Under its gainsharing demonstrations, Medicare continues to pay hospitals and physicians separately under the current fee-for-service methodologies, but hospitals are permitted to provide incentives to physicians to reduce costs and improve quality outcomes.

ACE Demonstration

Recently, another bundled payment demonstration, the Acute Care Episode (ACE) Demonstration, has been designed and implemented modeled on the CABG and centers of excellence demonstration initiatives. The ACE Demonstration is a three-year program that began in the spring of 2009. The demonstration involves a discounted bundled payment for all hospital and physician services for a group of inpatient cardiovascular procedures (CABG, heart valve, defibrillator and pacemaker implant, and angioplasty) and orthopedic procedures (hip and knee joint replacement). Because of the complexity of billing and claims payment under a bundled payment approach, the solicitation for applicants was limited to physician-hospital organizations (PHOs) located in states within the jurisdiction of one Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC). Applicants were required to provide a competitive bid by Medicare Severity-Adjusted Diagnosis-Related Group (MS-DRG) for either cardiovascular procedures, orthopedic procedures, or both. Sites are permitted to enter into gainsharing with physicians and allied professionals to provide incentives to improve quality and cost efficiency. Unique to this demonstration is that Medicare will share

50 percent of the savings it realizes from the discounted prices with the Medicare beneficiary, up to the amount of the annual Part B premium, currently $1,157. Sites are designated as “Value-Based Care Centers” and are encouraged to market their programs to referring physicians and Medicare beneficiaries. Five PHOs were selected to offer orthopedic or cardiovascular services, or both. Price discounts range from 1 to 6 percent, varying by site and by type of procedure.

Lessons Learned

Prior and current demonstrations have shown that a bundled payment program inclusive of all facility and physician services for an episode of care can effectively realign service and utilization incentives to yield cost efficiencies and quality improvement outcomes for the provider with considerable savings to the patient and insurer. However, the cataract demonstration also showed that the healthcare episode must involve a sufficient number of healthcare resources to provide the potential for increased efficiencies. Complex, high-cost inpatient procedures that involve significant but standardized services offer the best opportunity for cost savings and quality improvement. In addition, a carefully designed gainsharing program can elicit creative initiatives and broad provider involvement in efforts to improve quality outcomes while reducing unnecessary costs.

BUNDLED PAYMENT: PHYSICIAN ENGAGEMENT ISSUES

George J. Isham, M.D., M.S.

HealthPartners

Many policy experts advocate a move to bundled payment approaches to address the perverse incentives associated with fee-for-service payment systems. Despite near consensus among policy makers about the benefits of bundled payments, little practical experience informs the issues that may be encountered in implementing this strategy. In this paper, four experiences in Minnesota with varied bundled payment systems highlight the variation and limitations of bundled payments. However, from these experiences, we can glean key lessons about the implementation of these systems and define some of their policy implications.

Commonly cited policy objectives for bundled payment systems include (1) increased efficiency (lower cost of care), (2) coordination of care, and (3) improved quality of care (when combined with pay for performance). However, while looking at four manifestations of bundled payment systems in Minnesota, it becomes clear that not only are there critical lessons to

learn but not all of these systems do in fact target these objectives. As a result, these systems may be moving in directions that arrive at different places with regard to cost savings potential.

Lessons from Carol.com

Carol.com is a bundled payment initiative in Minnesota that focuses on improving the way consumers interact with the healthcare system, improving cost transparency, and encouraging a market for health care driven by open choice and competition. A “care package” (bundled care) gives a detailed description of a treatment or service so that a patient knows exactly what to expect before going to the doctor and exactly what is being provided for a stated price. Care packages are designed, priced, and placed in the consumer-directed carol.com online marketplace by individual providers. Two markets are currently active, Seattle and Minneapolis. This approach is intriguing and attractive because it is consumer focused and has the potential to be more readily understandable by patients. Unfortunately, there has been limited consumer purchasing volume in the online marketplace so far. Until such time as this approach is a dominant market paradigm for purchasing care, we feel that it has very limited cost savings potential.

Lesson from Minnesota “Baskets of Care” Initiative

The objective of the State of Minnesota Baskets of Care initiative is to encourage providers to cooperate and develop innovative ways to improve healthcare quality and reduce costs through the development of seven “baskets” or bundles of care by January 1, 2010. The steering committee identified asthma in children, diabetes, acute low back pain, obstetric care, preventive care in adults, preventive care in children, and total knee replacement as the seven initial bundles. Working groups drawn from stakeholders and experts and facilitated by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement have defined the contents of each of the baskets. Quality measures that describe the quality of care of each of the baskets and administrative and implementation challenges for all of the baskets are in the process of being identified as this is written. The legislation calls for a single price to be established and ultimately posted publicly by each provider for the baskets that must be adhered to by all payers (with some government exceptions). Price and quality information for each basket by provider are to be public by July 1, 2010. In Minnesota, opinions vary on the potential of this initiative for cost savings.

Lessons from Prometheus Payment System

The goals of the Prometheus Payment system are (1) to encourage physicians, hospitals, and other providers to work as a team centered on each patient’s needs, irrespective of their administrative integration, and (2) to improve margins as they reduce care defects. A more complete description of Prometheus was provided in the July workshop in this series. At HealthPartners, we have had the opportunity to pilot the Prometheus AMI (acute myocardial infarction) bundle in our commercial populations. We found that we have small numbers of patients with AMI in that population. In Minnesota, we have worked hard with considerable success to encourage adherence to best care clinical guidelines for cardiovascular disease, and our commercial populations have been the target of excellent preventive care and health behavior change interventions targeted at cardiovascular risk factors for more than a decade. As a result, there is limited opportunity to reduce total cost of care when the focus is reducing potentially avoidable procedures and complications for an AMI episode. In addition, HealthPartners evaluated other high-volume procedures as potential candidates for this payment methodology. Similar to AMI, the results of our analysis suggested limited opportunity to reduce total cost of care for procedure-based episodes. We understand from other Prometheus pilot sites and Prometheus staff that chronic conditions may offer better opportunities for reducing potentially avoidable care and therefore reducing cost of care in Minnesota. This raises the issue of variable cost savings opportunity by condition or procedure by region of the country for this and other bundled payment approaches, a situation that should not be unexpected given the work of Wennberg and Fisher on regional variation in care.

Lessons from Use of Episode-of-Care Analytic Tools

At HealthPartners, we have used commercial episode treatment groups to provide analysis of claims experience to the medical groups serving our 850,000-member health plan. This includes our own medical group (HealthPartners Medical Group) of more than 650 physicians in over 30 locations providing both primary and specialty care to approximately 250,000 of those health plan members. Because the medical groups that serve our plan population, including the HealthPartners Medical group, are placed in tiers for many of our insurance products by both cost and quality, there is interest in achieving a high-quality and low-cost position for the most favorable tiered position. Patients selecting care with physicians in medical groups in the most favorable tiered position benefit by having lower copayments for care. Episode treatment group analysis is used to analyze practice patterns and identify unwanted variation in care. As a result of in-

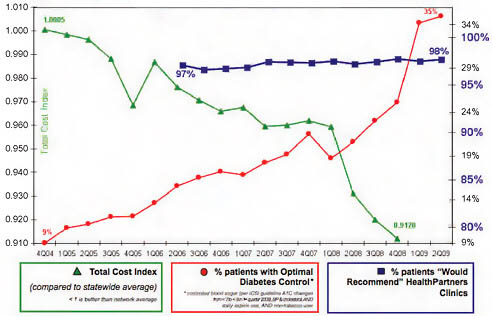

tense focus to achieve consistency in care and coordination of care through the design of reliable systematic care processes, supported by an electronic medical record, we have been able to achieve increases in quality of care, high levels of patient satisfaction with the experience of care, and reduction in the relative cost of care for HealthPartners Medical Group from slightly more than the average cost of care in our market to 8 percent below the average cost in a period of about 4 years (Figure 15-1). In integrated care systems, global incentives to achieve reductions in total cost of care, the use of episode-of-care analytic tools, and many other efforts can result in reductions in total cost of care relative to market averages.

Tying Together the Lessons Learned

These experiences in Minnesota demonstrate that the objectives of these conceptually similar efforts vary and that the cost savings potential of some of these models is controversial.

-

Systems dependent on transparency and consumer choice must have significant market share. While innovations such as online

FIGURE 15-1 Triple aim: health-experience-affordability.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from HealthPartners, Inc. HealthPartners, 2009.

-

marketplaces are promising and exciting, until they become the dominant market paradigm for purchasing care, the cost savings potential is limited.

-

Building these systems is difficult and resource intensive. Design and development is important and resource intensive and must be carefully executed—from the enabling legislation, to expert development of the tools and payment systems, to the testing of feasibility and practicality by practitioners and payers in real markets.

-

Impacts may vary by region and by procedure. Potentially avoidable care and efficiency of care may vary by procedure and condition by region of the country, presenting differential regional opportunities for cost savings.

-

Formal organizations that support integrated systems are better positioned for success. Corrigan and McNeill have observed that “clinically integrated systems of care are better positioned to design safe, effective, and efficient longitudinal care processes for patients with chronic conditions. With clinical integration, performance measurement and improvement can extend across each entire patient-focused episode and can help inform and redesign the whole care process” (Corrigan and McNeil, 2009). Kahn observes that “to maximize the chances of success and minimize the possibility of unintended consequences (of payment reform), the appropriate culture and structure of health care institutions first must be in place” (Kahn, 2009).

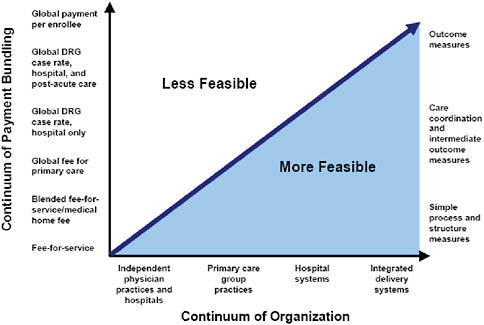

Figure 15-2 suggests that increasing integration of the care organization enables the feasibility of more bundled payment arrangements and the collection and reporting of more sophisticated outcome measures of quality of care. Review of Howard Miller’s presentation to the July workshop in this series, supplemented from experience with bundled payment in Minnesota, indicates that the design of bundled payment is a complex task that must be carefully executed to achieve the desired policy objectives.

Although some would assert that “virtual integration” is a possibility for physicians to work with hospitals and other providers in prospectively managing bundled care across time and organizational boundaries, participants in designing care packages for carol.com or Baskets of Care for the State of Minnesota are reluctant to design bundles with components that are out of their organizational span of control. Some physicians have very little trust or comfort in other organizations’ acting as the financial integrator for bundles of care in which they participate. Small or individual practices may require technical help from a payer or a larger, more sophisticated, organizational provider partner to understand how to evaluate and participate in bundled payment arrangements. For payments across

FIGURE 15-2 Organization and payment methods.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from The Commonwealth Fund, 2009.

organizational boundaries, a lead “integrator” may be required to accept the bundled payment and manage the distribution of that payment to individual smaller practice entities participating in the arrangement. How that subpayment is arranged, how the coordinating mechanisms are designed and deployed, how the effort is expended to develop a common understanding of the objectives (common culture), and how the redesign of care is executed to achieve better bundle performance will be important elements in determining the success or failure of implementation.

It is less difficult but still not easy to achieve the degree of cooperation required for success even in existing integrated organizations. This will be even more difficult in situations where cooperation is required across formal organizational boundaries. The form of payment and the degree of integration of care are strongly interdependent factors that lead me to the conclusion that planning for implementation of payment reform must proceed in close harmony with planning for reforms in the structure and function of the delivery system itself. The various proposals for the development of accountable care organizations (ACOs), if implemented, may go a long way toward creating the capability in the existing fragmented and disorganized care system to effectively manage bundled payments for care. It is important to note, however, that in any of these systems, bundles them-

selves do not intrinsically address inappropriate indications for services, and the potential exists for bundled procedures to be gamed to increase inappropriate hospitalizations and procedures.

Again, bundles arrive in a very complex and fragmented clinical, payment, and administrative environment, creating challenges for implementation. In 2009, implementing bundled payment pilots is resource intensive, requires sophistication, is complex, is not automated, and layers on an existing FFS payment system. Everyone currently involved in the bundled payment efforts in Minnesota is confused about how “Health Care Homes” (our medical home initiative in Minnesota), bundles of care, and accountable care organizations (being contemplated for development in Minnesota) relate to one another as payment reform initiatives and in practical operational terms as pilots for these initiatives are developed and deployed. Some ask how many times and how many providers will be paid for coordination of care since coordination of care is an outcome for these three payment or structural reform concepts.

Translating to National Implementation and Reform

Some key issues for national implementation of bundled payment include the need for coordination of Medicare and state-funded programs (“harmonized” payment methods) with the private commercial market (as Medicare does with DRGs for hospitals). Regional variation is important; implementation of new payment programs should not add to the problems created by perverse incentives in existing federal payment policies (the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale [RBRVS] and the distortion in relative payments to primary care and specialist physicians, and regional Medicare payment variations).

To achieve the maximum savings potential, bundled payment systems should be designed by experts as a comprehensive payment system with the input of providers and other stakeholders and judged against clearly defined policy objectives. For both federal and state policy makers, an overall model of payment reform that addresses the potential conceptual and operational conflicts between the medical home, accountable care organizations, and bundled payment initiatives is needed. Appropriateness of care needs to be explicitly addressed and incorporated into the design of the bundle. Care should be taken with respect to the special interests undermining the intent in government-designed bundled payment programs through political influence (e.g., comparative effectiveness research and its application to benefit design, etc., under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act [ARRA]). Engaging providers and other stakeholders is important to the successful implementation of bundled or any other payment reform.

Currently, provider attitudes toward bundled payment vary from en-

thusiastic to hostile. With such a complex reform, technical assistance on management and quality improvement at the local level should be provided to address provider and payer organization concerns about their ability to succeed with implementation. It will be important to provide a way for all to win if performance against cost and quality for patients is to be improved—in both high- and low-performing regions of the country.

PATIENT PERSPECTIVE AND PAYMENT REFORM

Nancy Davenport-Ennis

National Patient Advocate Foundation

As we embark on the national discussion about health care and payment system reform—its policy and politics—it is critical that we attack the issue of bundled payments from the patient perspective. For although we may not be a patient today, we may have been one yesterday, we may become one tomorrow, but we are assured at some point that either we or someone very near and dear to us will be a patient. While the voices of providers, payers, policy makers, researchers, and other stakeholders have been loudest in the debate, it is the patient who is at the center of the system.

Bundling payments in the U.S. healthcare system is an activity that requires us to get it right for patients. Patients need the system to do this well. They need the payment system to be deliberate. They need reform that looks at cost savings through a prism that is going to ultimately afford greater quality of care and greater opportunity for physicians and patients jointly to examine what the cost, benefit, and risk to the consumer are going to be.

Engaging Patients Meaningfully

An important first step is to grapple with patient engagement. Patient engagement includes actions that individuals must take to prevent disease and obtain the greatest benefit from knowledge of both disease prevention and the healthcare services available to them. However, patient engagement needs to be encumbered with the reality of those of us who are patients and are trying to become engaged in this arena of thinking and decision making. What is not considered in this definition is that often patients are under great duress and stress at the time they are trying to be engaged in the healthcare community. Patients are often suffering with pain. They are often suffering with non-descriptive symptoms that may or may not cloud their ability to become active in their own decision making. Just as likely, they may not be able to understand clearly the information provided to them under these circumstances. The need for patient engagement that accounts

for these realities becomes that much more important as we move toward a bundled payment system, but today’s failures at patient engagement leave us far from the mark of where we need to be.

As an illustration, 4 years ago, one of my family members was diagnosed with a Stage 4 cancer, with a projected remaining life span of 120 days. Furthermore, there was less than a 30 percent chance that any intervention would be favorable. My family represents many well-informed healthcare consumers, and we asked the obvious questions, including “What are the costs for the care?” Yet, after 5 months, we still did not have an answer about the cost, and this was a family that was persistent, well educated, and well informed. So as we begin to talk about bundled payments, we are indeed asking the nation to make a fundamental paradigm shift.

Patients need information that they have never had before. Also, because they have not had it before, they need support in making sense of it and using it to drive decisions. What questions do they need answered? Here are a few: What is the cost of treatment? How much is being saved by reforms? Where do the savings go? What are the effects on me as a patient and consumer? How do we measure success of reform—fewer dollars spent, higher quality and better outcomes, both?

Of course, bundling is not a brand new concept. We have had diagnosis-related groups for a long time in the United States that bundle the costs of inpatient hospital services. However, if a patient were admitted today through the emergency room and asked whether any of the services she was about to receive would be part of DRG, she might or might not get a clear answer. If she asks about the cost share for her and her family for the DRG billing, again there is a significant chance that she will not get an answer today, tomorrow, or next month. She will likely have to wait for her first explanation of benefits (EOB). So even though this “new” reform has been in practice at some level for years, the call for patient engagement has not been answered. Fortunately, there are places that are more successful at patient engagement, and looking at the Geisinger Health System is informative in that regard.

Bundling Clearly and Flexibly

Beyond the issue of patient engagement, looking forward to payment reform and bundling requires attention to creating bundles that make sense. Some treatment protocols can be very neatly packaged. They have clear beginning dates; they have clear end dates; and there are very specific bands of services that occur within a framework. Here, bundling probably works very well. However, bundling works less well when the diagnosis is complex and there is not a single, clear, prescriptive therapeutic intervention. Part of that lack of clarity rests with the underlying comorbidities of the patient.

If bundling is going to be successful for the patient, we must consider weighted outliers and devise a system that, while defining a diagnostic and treatment pathway within a bundle, allows for meeting the patient’s need should he fall outside of the standard parameters.

Engaging Patients Through Education

Bundled payment systems are and will continue to be complex, if for no other reason than they need to be flexible and pliable in the face of patient needs. Yet, as complicated as these systems are, patients need simple, straightforward information and ready access to it. We would suggest that with any bundled payment reform, not only does it have to engage patients and meet the needs of all patients, it has to include a public education campaign. Educating patients, doctors and providers, insurers, and other stakeholders about the bundled payment system requires a concerted effort at the national level. Patients need to understand the risks and the benefits of all the services that can be made available to them. Nonprofit patient groups are going to have to wade into this water and help their constituents understand what the bundled packages of standard care mean for patients in specific disease groups. Insurers will have a tremendous responsibility to further educate the employers to whom they are selling policies.

Conclusion

Patients are the centerpiece of the healthcare system. It is they who are served by providers, payers, and policy makers. Yet their voices are often the least considered in the debate. As the direction of healthcare reform moves appropriately to bundled payments and the creation of coherent pathways of diagnosis and treatment, we must remember the needs of patients. Meaningful patient engagement is critical. Bundling healthcare services must allow for all patients to be served, regardless of the complexity of their cases or their comorbidities. In addition, patients and all stakeholders need accessible and robust education about the impact of these reforms on their everyday lives and practices.

REFERENCES

The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System. 2009. The path to a high performance U.S. health system: A 2020 vision and the policies to pave the way. New York: The Commonwealth Fund.

Corrigan, J., and J. D. McNeil. 2009. Building organizational capacity: A cornerstone of health system reform. Health Affairs (Millwood) 28(2):205-215.

de Brantes, F., M. B. Rosenthal, and M. Painter. 2009. Building a bridge from fragmentation to accountability—The Prometheus payment model. http://www.nejm.org (accessed August 26, 2009).

Donabedian, A. 1984. Volume, quality, and regionalization of health care services. Medical Care 22(2):95-97.

Flood, A. B., W. R. Scott, and W. Ewy. 1984. Does practice make perfect? Part 1: The relationship between hospital volume and outcomes for selected diagnostic categories. Medical Care 22(2):98-114.

Health Care Financing Administration. 1992. Unpublished analysis of Medicare provider analysis and review (MEDPAR).

Hughes, R. G., S. S. Hunt, and H. S. Luft. 1987. Effects of surgeon volume and hospital volume on quality of care in hospitals. Medical Care 25(6):489-503.

Kahn, C. 2009. Payment alone will not transform health care delivery. Health Affairs (Millwood) 28(2):216-218.

Luft, H., S. S. Hunt, and S. C. Maerki. 1987. The volume-outcome relationship: Practice makes perfect for selected referral patterns. Health Services Research 22(2):155-182.

Office of Inspector General. 1987. Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Showstack, J. A., K. E. Rosenfeld, D. W. Garnick, H. S. Luft, R. W. Schaffarzick, and J. Fowles. 1987. Association of volume with outcome of coronary artery bypass surgery: Scheduled vs. nonscheduled operations. Journal of the American Medical Association 257(6):785-789.