3

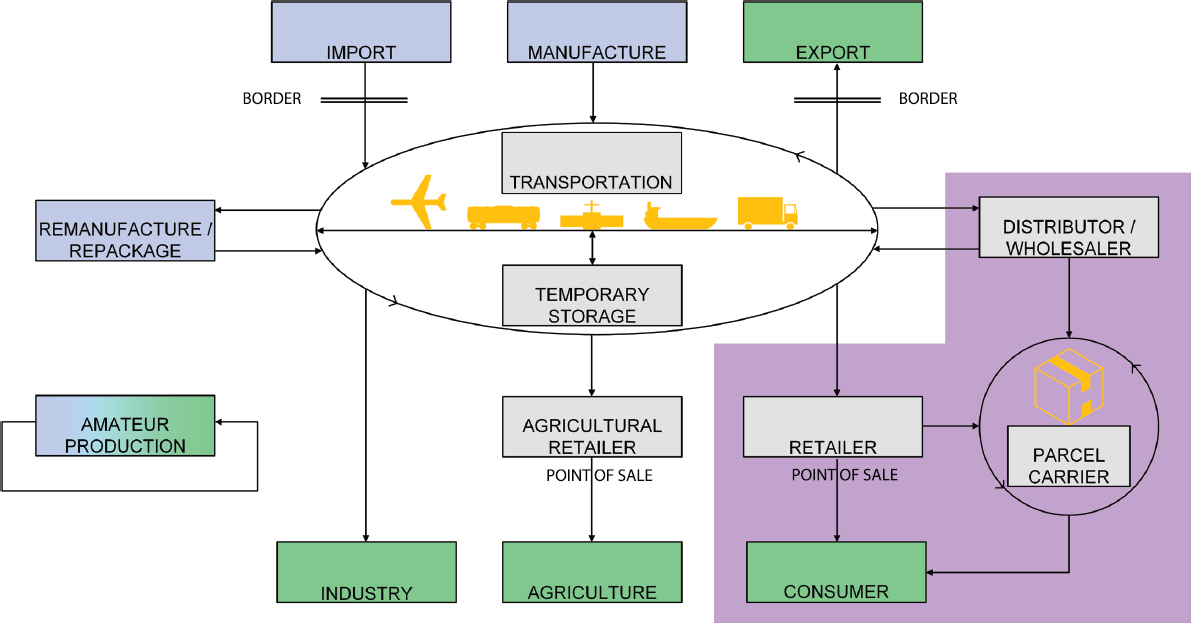

Domestic Chemical Supply Chain

This chapter characterizes the movement of precursor chemicals through domestic supply chains and the potential vulnerabilities inherent in those supply chains, based largely on the presentations provided during the data-gathering meetings. It does so by (1) mapping a supply chain, in general, for the precursor chemicals; (2) cataloging and overlaying existing domestic policy mechanisms that may improve the security of those precursor chemicals; and (3) singling out gaps in supply chain visibility and oversight. Of particular security concern are the possibilities of unexplained losses, diversion, theft, and other misappropriation of precursor chemicals at the nodes and in modes of transportation throughout the supply chain. Several policy terms used in this chapter are defined in Box 3-1.

In the course of describing the domestic policy landscape, the committee does not present evidence on the effectiveness of any particular policy mechanisms because the evidence is largely unavailable, but the committee does highlight some of the costs, including unintended consequences to businesses and users. The committee was able to obtain information on compliance and participation rates for some security programs, but not on the programs’ contributions to risk reduction per se. The evidence might be missing because of the methodological challenges of discerning risk reduction (Appendix B) or the limited development of retrospective assessment.43

In this report, the committee does not discuss the quantities of precursor chemicals moving throughout the domestic supply chains in detail. That information would not provide insight on mechanisms to restrict access given that the amounts of precursor chemicals required to make a person-borne improvised explosive device (PBIED) are many orders of magnitude smaller than

the amounts contained throughout the commercial supply chain. For example, a representative of Yara International reported that 75 kilotons per year of calcium ammonium nitrate (CAN),44 itself one of the less common Group A precursor chemicals, are imported into the United States, which is enough to construct about 12,000 Oklahoma City–size charges. Furthermore, in 2012, only 0.1 percent of the Pakistani CAN production was required to be smuggled into Afghanistan to meet the needs of insurgents.45 Secondarily, while some trade groups can provide an estimate of the precursor chemical mass moved per annum, the ability to know where smaller quantities, outside of the initial bulk shipments, are be-

ing moved and consumed is beyond the scope of this committee. The committee does not discuss specific international entry points either.

The supply chains described in this chapter are specific to the present state of domestic commerce within the United States and do not necessarily apply to in-theater procurement activities in which bomb makers are currently engaged.46,47 The committee received data on how groups can source materials from manufacturers around the world through legitimate channels, then move them from more stable adjacent countries to feed their activities.48-50 Countering the flow of goods into these areas will require an international effort,51 which is also beyond the scope of the committee’s charge with respect to domestic access.

SUPPLY CHAIN OVERVIEW

Supply chains consist of multiple processes and activities, within and between companies, from planning and procurement, through the time when a product or material is transported, until it is delivered to the end user. Supply chains provide a virtual map of how commodities, raw materials, works in process, and finished goods move from origin to consumption or other end uses.52 In the United States, supply chain transactions are well documented, providing visibility into who has possession of, who has specific responsibilities for, and who is the ultimate user of the product or material in question. This section provides an overview of general supply chains. Details about the supply chains of individual precursor chemicals in Group A can be found in Appendix D.

For example, a company might document the planning and forecasting processes leading up to placing a purchase order. The information used in these processes might include historical sales or consumption data and forward-looking estimates of customer needs based on marketing knowledge. Companies use the planning and forecasting processes to limit inventory and ensure adequate free cash flow for other needs. The forecast generally results in a purchase order that provides specific information regarding product quantities, specifications, point of origin, shipping destination, negotiated pricing, and expected delivery dates. In most organizations, this information is generated and stored electronically.

Subsequent documentation will include purchase order confirmations, the shipping mode, the carrier name, and bills of lading that may spell out specific requirements and possible regulatory responsibilities. Since most transactions are now tracked electronically, visibility of transfers and the movement of products and materials have improved dramatically in the last two decades. Just as consumers can track an online order from its origin to their home or office, so can companies track their orders electronically from purchase order to delivery, often with great confidence in the data.53 While many companies focus on the benefits of improved visibility for inventory management, improved visibility may also make it easier to identify, track, and monitor suspicious product movements.

At the conclusion of any shipping process, a proof of delivery—physical or electronic—will be generated to verify that products or materials were received at a certain location in specific quantities.54 In the case where products or materials are subsequently shipped to distributors, retail outlets, or consumers, additional documentation will be generated to indicate method of shipment, carrier, quantities, ship-to locations, and proof of delivery. Reports on in-transit incidents or accidents may also include information that can be helpful in reconciling total quantities of material when products are missing.

The most difficult part of the supply chain to document with surety is the final transaction to the end user. This is especially true if the transaction consists of unregulated materials or substances that fall below regulated thresholds (weight, volume, or concentration) or if the transaction is conducted with cash.

Some supply chains are very short or self-contained. For example, a company might manufacture a precursor chemical that it subsequently uses in an internal process, or ship a precursor chemical directly to an end user who then consumes it. The precursor chemicals might be used to manufacture additional, differentiated products for resale or might be applied in another process. In such cases, companies may provide their own internal transport by truck, rail, barge, or pipeline. Documentation for these moves, unless otherwise regulated, may be difficult to track.

Supply chains that extend beyond the boundaries of a single enterprise generally adhere to accepted practices for documentation and regulation. State and federal regulations apply to almost all shipments of goods, with special emphasis placed on materials that are caustic, toxic, or flammable, where weight and volume limits may be placed on shipments depending on the mode of shipment. This includes all supply chains that ultimately service or employ distributors, wholesalers, retailers, resellers, or consumers.

Throughout the study, the committee received data from industrial sources and trade groups on the supply, use, and consumption of precursor chemicals. Using this information, it constructed diagrams to illustrate how the chemicals move throughout the domestic supply chain (see Appendix D). Though the chains of the chemicals serve different industries and end users, there are many commonalities in the types of nodes that the precursor chemicals encounter as they move from origin to end use.

Figure 3-1 illustrates how precursor chemicals might move through a typical supply chain. Precursor chemicals enter the U.S. supply chain through imports or manufacturing operations and are subsequently transported by various shipping modes to points of use or to intermediate storage locations—such as distributers, wholesalers, or retailers—before being sold to customers. Each box in the illustration represents a node in the supply chain that constitutes a point of origin, mode of transportation, interim storage location, transfer of ownership, or end use. Chemicals enter the supply chain as precursor chemicals at blue nodes, are stored at gray nodes (excluding transportation), and are transformed

into something chemically different or consumed directly at green nodes, while the nodes on a purple background indicate the possibility of e-commerce (see Appendix D for a full glossary of node designations). The following sections detail the types of nodes present on this diagram.

Production and Input Nodes

In Figure 3-1, blue nodes indicate where precursor chemicals enter the supply chain. These nodes include import, manufacture, and re-manufacture. Amateur production is unique in that it is a closed system. The green export node is discussed here as well.

Import/Export

The import and export nodes encompass transportation of the precursor chemicals into (import) and out of (export) the United States from or to foreign countries, either as bulk materials or finished products. The nodes are separated on the chart for conceptual clarity, but transactions in either direction will occur at the same physical locations. Specific locations may include seaports where large container ships offload their goods (e.g., CAN prills produced in Europe)44 or land-based border crossings with Canada and Mexico (e.g., caustic or high-water-content precursor chemicals such as hydrogen peroxide).55 Most ports also include terminal facilities for temporary storage or transloading; however, for clarity on the supply chain charts, these are treated as either part of the port node if covered by the Maritime Transportation Security Act (MTSA, see below) or as a variant of a commercial distributor if covered by the Chemical Facilities Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS).

Manufacture

The manufacture node refers to domestic locations where precursor chemicals are made from other raw materials via a chemical synthesis or industrial process. Such factories may either produce a precursor chemical directly or as a by-product of another process. An example of a direct synthesis would be the manufacture of nitromethane from hydrocarbons. Or, as seen with ammonium nitrate (AN) manufacturing, the excess nitric acid by-product is sold to other end users.

Remanufacture and Repackage

Unlike primary manufacture, remanufacture and repackage operations acquire bulk precursor chemicals and either incorporate them in further formulations or split them into smaller packages, with the requirement that the precursor chemi-

cal remains the identical chemical species before and after the reformulation. An example of remanufacture would be a match factory that uses potassium chlorate to make the match heads, while repackagers include locations that bag precursor chemicals as ingredients for fertilizer blends.

Amateur Production

The committee acknowledges that hobbyists and other members of the public can synthesize certain precursor chemicals themselves from readily available raw materials. An individual manufacturing precursor chemicals could ship or transfer them to another person through a carrier or other means; however, the committee does not have access to data to either confirm or deny that this occurs. To reflect the dual synthetic and consumptive role of these individuals, the node is colored blue and green. While instructional materials for at-home precursor synthesis are readily available, the committee does not list specific references or detail these protocols.

Transportation Modes

Transportation here means the loading, movement, storage incidental to movement, and unloading of property, including solid, liquid, and gaseous materials. The Group A precursor chemicals are either solids or liquid mixtures (e.g., some sodium chlorate and all urea ammonium nitrate (UAN) solutions are liquids during transport), and transportation is conducted primarily by vehicles. Shipment may occur in a wide variety of packaging formats, ranging in size from large tanks and hoppers for bulk materials to bottles and boxes for small quantities. During transport, the owner of the precursor chemical may have title, but not necessarily physical possession, in which case, the carrier might be obligated by contract or law to insure the owner against all or partial loss. A person who places a precursor chemical into transportation in commerce is defined as a shipper, whereas a person who performs the transportation function is a carrier, and both designations may apply to the same person. Carriers may be for hire—that is, a common carrier that transports property in commerce based on a fixed price for any person or entity—or private. A private carrier transports property it owns or for limited persons or entities under contract.

Ship and Barge

Precursor chemicals are imported and exported via ocean freight and may be transported domestically along inland waterways. In both cases, vessels move precursor chemicals in bulk as solids and powders in dry holds, sometimes bagged in bulk-size sacks, or as liquids in tankers.

Truck

Trucking is a major mode of transportation for both bulk material (e.g., hopper or tanker trucks) and small quantities and formulations of precursors (e.g., dry van and tractor trailers).

Rail

Rail is used primarily to transport bulk materials in tank cars, hopper cars, and boxcars. Certain precursor chemicals that are transported by rail require specialized means of containment because of their corrosive nature (e.g., nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide) or physical properties.

Air

Due to the high cost per volume of transport, only small quantities of precursor chemicals are shipped via air freight, mostly for specialty or individual use.56 This shipping will fall primarily within a parcel carrier’s distribution system.

Parcel Carrier

Shown separately in Figure 3-1, parcel carriers (e.g., USPS, UPS, FedEx) use trucks for the final delivery of small quantities of precursor chemicals to consumers. They employ their own distribution systems, separate from those of the transportation nexus, which may include truck, rail, and air shipping modes.

Pipeline

Within the United States, a several-million-mile-long pipeline network gathers, transports, and distributes gases and liquids to commercial and residential customers. The only case where a precursor chemical is transported via pipeline, outside of the relatively short pipelines within chemical plants, is in the distribution of UAN. Pipeline networks deliver that product to terminals for domestic distribution or for export.

Distribution and Retail Nodes

The gray boxes on Figure 3-1, other than transportation, are broadly grouped as locations where the precursor chemicals are physically stored and recorded for future sale and use, either in large or small quantities. Most of these locations differ from temporary storage locations insofar as title and responsibility have passed from the manufacturer or supplier to an entity that will ultimately distribute the product to consumers or other end users.

Temporary Storage

It is not uncommon for precursor chemicals to reside in temporary storage locations during transport (e.g., AN prills transferred to rail-side hoppers) for either short or extended periods of time while awaiting further movement or transloading.57 These nodes are considered separate from distributors as they represent a transitory stopping point en route to a specific location.

Distributors and Wholesalers

Finished product may be sold to an intermediary that will hold the product in inventory, awaiting resale to other nodes. Distributors may work with specific products or with chemicals in general (chemical distributors), or may serve as warehouses and wholesalers for a variety of goods. The committee learned that some distributors also break bulk shipments of materials into smaller portions or allotments, for example, the bagging of AN fertilizers.

Agricultural Retailers

Agricultural retailers are considered a separate node because their customers and the uses of the precursor chemicals are highly specific. In this study, agricultural retailers are defined as local businesses that sell bulk quantities of agricultural chemicals to agricultural end users, as defined below, and store them onsite. The committee learned that many agricultural retailers provide application services to their customers, thus maintaining physical custody of the precursor chemicals until they are dispersed, and that a minority of these retailers bag products on request.58

Retailers

Products are sold to consumers, commercial and noncommercial, by entities designated on the chart as retailers. This node can assume a variety of forms, from physical home improvement stores and pharmacies to online storefronts and platforms.

End User Nodes

The green nodes in Figure 3-1 represent locations where precursor chemicals exit the domestic supply chain. This can be accomplished by export out of the domestic supply chain (see above), by chemical reaction transforming precursor chemical into a different species, or by the ultimate use of the chemical.

Industry

Industrial end users encompass manufacturers that convert a precursor chemical into another chemical or finished product, in which it is no longer the same chemical species. For example, one of the primary uses of hydrogen peroxide is in the pulp and paper industry as a bleaching agent, where it is consumed.55 A finished product process might include cold casting aluminum powder, which transforms the powder into a solid piece of metal. Industrial uses not covered by this node are those that simply mix precursors without changing their chemical properties, such as the blending of nitromethane with furfural to make agricultural products; these users are considered remanufacturers or repackagers.59

Agriculture

This node is defined as commercial operations, ranging from family farms of a few acres to large-scale facilities, that grow food crops or other plant products. While farmers with landholdings across the size spectrum account for a significant portion of the node’s end users, this node also includes other professionals such as landscapers and other horticulturists.

Consumer

In Figure 3-1, and throughout the report, a consumer is defined as a nonindustrial, nonagricultural end user who employs a precursor chemical directly for either commercial or noncommercial activity. The commercial category includes cosmeticians, who use peroxide-based bleaching products, and jewelers, who use nitric acid in metal finishing kits. Noncommercial uses by the general public, range from personal hygiene and home care to pyrotechnic and rocketry hobbies, but are limited to personal needs.60

Internet Commerce

E-commerce presents unique challenges to restricting access to precursor chemicals. The reach of the internet across municipal, state, and national borders can enable potential buyers to bypass local restrictions by purchasing from retailers in other jurisdictions, under different rules. Moreover, a buyer can remain anonymous by masking its identity behind multiple layers of obfuscating cover and using nonidentifying methods of payment or making purchases via the dark web, which is a venue for illegal activity.61

To the committee’s knowledge, all the precursor chemicals in Group A can be purchased online and shipped to end users, including private individuals, from multiple sources. In some instances, retail sites automatically present buyers with purchase ideas, such as “People who bought chemical X also bought Y,” thus suggesting, though not identifying it as such, an ingredient list for an explosive

combination. That is not to say that a substantial share of internet sales of precursor chemicals lack legitimacy; for example, AN, nitromethane, and aluminum can be used in exploding targets, racing fuels, and pyrotechnics, respectively.

While online transactions can occur throughout the supply chain, this report limits the discussion of e-commerce to direct, consumer purchases from retailers or finished product manufacturers, delivered via a parcel carrier service, along with any transportation methods used to deliver those products. E-commerce sometimes blends node designations when the finished product manufacturers sell directly to consumers; however, for the purposes of the report, manufacturers retain their manufacturing designation, with the purple e-commerce zone and shipping arrows indicating consumer sales on the supply chain charts.

The committee learned that two types of e-commerce websites tend to sell precursor chemicals: retailers and platforms. Retailers are defined as companies that both provide the online storefront and fulfill orders. One class of retailers separated out on the supply chain diagrams (Appendix D) is the chemical supply companies that typically sell directly to research institutions or companies, with limited, sometimes vetted, sales to individuals.62 More common retailers include internet-only retailers (e.g., Amazon) and companies that also operate at physical locations (e.g., Home Depot and CVS), both of which sell broadly, without vetting. Platforms differ from retailers insofar as the website merely facilitates transactions between other parties. For example, eBay and Craigslist connect buyers and sellers, but do not list or fulfill any product orders themselves. Any website allowing communication between parties could potentially serve as a platform for e-commerce of precursor chemicals.

The accessibility and usability of e-commerce has raised new challenges for restricting access to precursor chemicals. Through online channels, chemicals can flow directly to consumers, across national, state, and municipal borders with relatively little visibility, absent direct interventions to monitor or track information on retail listings, orders, and purchases. Without a physical presence and the opportunity to engage face-to-face with the intended purchaser, the retailer cannot, for example, identify suspicious behavior beyond the decision to purchase a particular chemical or combination of chemicals, which might not be suspicious on its own. What could be suspicious behavior might only manifest through direct engagement. Another challenge is the difficulty of tracking multiple purchases of the same or complementary chemicals from different sources, both brick and mortar and online.

Internet retailers, like most other retailers, are not currently required to restrict the sale of precursor chemicals; however, some have promulgated their own restrictions (e.g., Amazon bans certain Department of Transportation [DOT] hazmat classes,63 and eBay maintains a list of banned chemicals64). However, these self-imposed restrictions do not always prevent the listing and sale of the targeted materials. For example, even if an internet retailer refuses to sell a material directly and does not allow others to sell it on the platform, other businesses

or individuals who sell through the platform (e.g., non-Amazon retailers who sell through Amazon or eBay users) might be able to circumvent the policy.

eBay works with law enforcement agencies proactively and on request and automatically filters, removes, and prevents online listings of sales of prohibited items.65 There are also reports of eBay-based transactions leading to the identification of potential suspects.66 The committee requested conversations with other online retailers. Lacking a response, the committee does not know whether eBay’s practices are industry-wide, or whether companies outside of the United States would work with domestic law enforcement agencies in any capacity.

DOMESTIC POLICY MECHANISMS

Federal controls that aim to halt bombing attacks have a long, if somewhat intermittent, history. In response to the United States’ entry into the Great War, Congress passed the Federal Explosives Act of 1917, which dramatically curtailed access to both explosives and the “ingredients” (referred to as precursor chemicals in this report) used to make them.67,68 This act was repealed after the war, then temporarily reinstated for the duration of World War II.

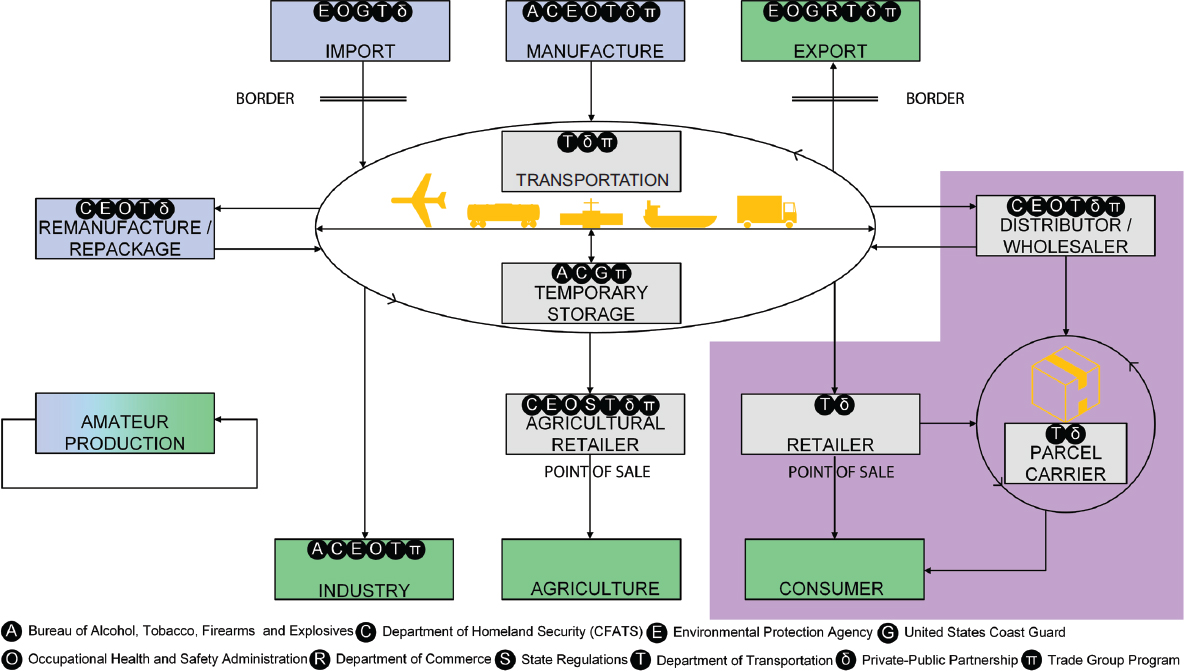

Presently, many policy mechanisms are in place throughout the domestic chemical supply chain that could directly or indirectly contribute to security objectives. Figure 3-2 shows that a wide range of controls and other policy mechanisms currently impact each node of the supply chain.

A policy mechanism, especially one that addresses security, can both reduce the probability that precursor chemicals will be used to make HMEs for use in IEDs and potentially mitigate the severity of improvised explosive device (IED) attacks should they occur (see Appendix B). Several of the mechanisms considered in this chapter are likely to impact probability more than severity. More specifically, they reduce the likelihood of IED attack consequences by securing the production, storage, or distribution of particular precursor chemicals.

The remainder of this chapter discusses the coverage of existing controls and other policy mechanisms to identify potential vulnerabilities. The sections discuss these controls and mechanisms, including private-sector initiatives, in greater detail. On the federal level, the controls—and the associated regulatory authorities—are sorted by department and agency. Consistent with the respective missions of each department or agency, the controls have different goals. For example, DOT’s hazardous material regulations focus on safety; the primary interests of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) are public health and environmental protection; and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) targets security with CFATS and MTSA.

Department of Justice

Attacks involving explosives are investigated and responded to by law enforcement at all levels of government. At the federal level, this falls under the authority of two Department of Justice (DOJ) bureaus, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).69 The latter is only concerned with incident investigations and counterterrorism operations, whereas the former also directly or indirectly regulates a subset of precursor chemicals and maintains the United States Bomb Data Center (USBDC), a national collection center for information on arson and explosives-related incidents throughout the country.

ATF directly regulates chemicals that are defined as explosive materials via a yearly updated list,70 but only regulates one of the identified precursor chemicals (ammonium perchlorate less than 15 micron).71 Nevertheless, ATF’s regulatory oversight will apply at those nodes where the precursor chemicals are manufactured into explosives. These regulations inevitably leave exploitable gaps because they do not cover precursor chemicals per se or, as a related matter, the sale and transportation of unmixed products, such as binary exploding target kits (see below). The absence of certain materials from the ATF explosives list also may not represent the physical properties of some precursor chemicals, a prominent example being AN, which is capable of detonation in a neat state as has been demonstrated historically.72-75 Although AN does not appear on the ATF explosives list, it is referenced as an “acceptor” subject to sympathetic detonation from the detonation of explosive materials stored nearby; AN is also considered a “donor” when it is stored within the sympathetic detonation distance of explosives or blasting agents, where distance is calculated using one-half the mass of AN to be included in the mass of the donor.76

A third DOJ agency that deals with precursors is the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), though for different purposes. DEA maintains lists of chemicals that are used in drug manufacturing, a potentially analogous activity to HME production.77 A “List I” chemical is a chemical that, in addition to legitimate uses, is used to illegally manufacture a controlled substance and is important to the manufacture of the substance; a “List II” chemical is a chemical that, in addition to legitimate uses, is used to illegally manufacture a controlled substance, but without the designation of importance. There is no overlap between DEA’s List I and the chemicals in Groups A, B, and C, but there is some overlap between the DEA’s List II and the chemicals in Group B, namely hydrochloric acid, potassium permanganate, and sulfuric acid.78 In addition, DEA’s Special Surveillance List includes one Group C chemical, magnesium.79 As with precursor chemicals used in explosives, drug precursors also have legitimate uses.80 The process used by DEA to control drug precursors can provide examples of the potential challenges and results of regulating precursor chemicals in certain ways (Box 3-2).

Department of Homeland Security

DHS is involved at several points along the precursor chemical supply chains through different offices and agencies: the United States Coast Guard (USCG) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) are involved at import and export nodes; the National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD) applies security requirements to those facilities manufacturing or storing certain precursor chemicals; and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) facilitates the credentialing of workers who move the products. Three DHS policy mechanisms are discussed in the next sections.

Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards

Initially authorized by Congress in 2007 and administered by NPPD, CFATS identifies high-risk chemical facilities via a screening procedure and regulates them to ensure that they maintain adequate security.18,85-87 A high-risk facility is defined as one that contains certain listed chemicals at or above specified threshold quantities and concentrations. The list of relevant chemicals is published as CFATS Appendix A and sorted as posing risks of release (public health), sabotage (public life and health), or theft and diversion (weaponizable).88 CFATS grants flexibility in the options for realizing adequate security, with DHS assisting the creation of workable security plans. Inspections to ensure compliance with the approved plans are concomitant.86 DHS is authorized to use compliance orders, civil fines, and cease operations orders to enforce CFATS.

Like many prioritization lists, CFATS indicates threshold quantities and concentrations that determine when the regulation applies, with most Group A precursor chemicals listed at 400 lb as theft or diversion security risks, the exceptions being AN (2,000 lb) and aluminum powder (100 lb). About 3,000 of the evaluated facilities eliminated the use of the relevant chemicals or brought their inventory below the prescribed thresholds or concentrations; in the case of hydrogen peroxide, several end users and distributors began to request 34.5% solutions (with 35% as the concentration limit in CFATS).55 There are also facility exemptions, including those covered by other regulations (e.g., MTSA) and, very specifically, water treatment facilities.89

A unique caveat is encountered at some ports that use terminals for transloading or temporary storage. If the terminal is within the grounds of the port, it will be covered by MTSA, while if it is not within that area it will be covered by CFATS. DHS presently does not plan to screen truck terminals for inclusion in the Section 550 regulatory program, and therefore DHS will not request owners and operators of truck terminals to complete the Top-Screen risk assessment methodology. For clarity, CFATS is not listed on the relevant supply chain diagrams at the port node, and the terminals are treated as a variant of a commercial distributor.

When constructing the CFATS Appendix A list, DHS encountered the same issue of ubiquity as described in Chapter 2. It reached the same conclusion: that prioritizing chemicals such as hydrogen peroxide and nitric acid instead of acetone and urea is the more logical choice. It cited the Academies’ 1998 study to support that determination.14

The presence of a CFATS Appendix A chemical at a facility does not necessarily imply that it is regulated under CFATS. Of the 60,000 Top-Screen assessments submitted by 38,000 unique facilities,90 only 2,570 are currently covered as high risk.91 This is a point of concern, as those approximately 35,000 remaining facilities do not have to implement security plans, either because they did not meet the statutory requirements or because they took preemptive action to reduce their risk profile by reducing the quantities of precursor chemicals below mass or concentration thresholds. Because the CFATS thresholds were designed with the goal of preventing vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIED)s, the current methodology for assessing facility risk may not be well-equipped for preventing access to person-borne improvised explosive devices (PBIED)-relevant quantities of precursor chemicals.

Maritime Transportation Security Act of 2002

Managed by USCG, the goal of the MTSA is to prevent a Maritime Transportation Security Incident, defined as “any incident that results in: loss of life, environmental damage, transportation system disruption, or economic disruption to a particular area.”92,93 This is accomplished by establishing security procedures at all U.S. ports and vessels based on terrorism vulnerability assessments. Mitigation strategies generally include surveillance, security presence, and credentialing and identification materials. MTSA does not directly regulate the precursor chemicals, but dictates the security procedures and precautions that all cargo must be subject to at ports, thus securing them indirectly. In addition to MTSA, USCG follows hazardous materials transportation regulations proffered by DOT (see below),94 while maintaining a sub-list of hazardous materials that require specialized handling procedures.95

Hazardous Material Transportation Credentials

Operators of trucks transporting hazardous materials, including most of the Group A precursor chemicals, are required to have a valid state-issued commercial driver’s license (CDL) with a hazardous material endorsement. To acquire an endorsement, the CDL holder must undergo a threat assessment, including a background check and vetting against the Terrorist Screening Database, and fingerprinting.96,97 MTSA requires a Transportation Workers Identification Credential (TWIC) for workers who need access to secure maritime facilities

and vessels.96 TSA conducts a similar security threat assessment to determine a worker’s eligibility to receive a TWIC.

Environmental Protection Agency

EPA focuses on protecting public health by preventing the release of precursor chemicals that may affect the population. Therefore, EPA regulations do not directly address precursor chemical security from the standpoint of misappropriation.

Toxic Substances Control Act

Under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), EPA has broad authority to issue regulations designed to gather health, safety, and exposure information; require testing; and control exposures to chemical substances and mixtures at chemical manufacturers and importers.98,99 TSCA gives EPA authority to take specific measures to assess the adverse health effects of new and listed chemical substances (>70,000) and to protect against unreasonable risks to human health and the environment from existing chemicals. Regulations may restrict or ban the manufacture, importation, processing, distribution, use, or disposal of any chemical substance that presents an unreasonable risk to human health or the environment. If the risk of a chemical substance is already managed effectively under a different statute, regulation under TSCA generally is not used.

All Group A chemicals except CAN and UAN are listed in TSCA, but regulation occurs only if the manufacturing facility exceeds 25,000 pounds per annum production. As of 2012, there are about 4,800 reporting facilities. CBP uses TSCA paperwork for imported chemicals before they are released from custody.100

Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act

The purpose of the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA)—which is not, strictly speaking, a control—is to provide local governments, first responders, and the public with information on the potentially hazardous materials in their communities and to facilitate emergency planning in the event of material release.101,102 This reporting may introduce an unintended security risk by providing malicious actors with information on the facilities that are storing precursor chemicals of interest.

Department of Labor

The Department of Labor (DOL) is concerned with the safety of workers who handle or are exposed in the workplace to chemicals, some of which are precursor chemicals that can be used to make explosives.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

A subset of the precursor chemicals listed in this report are regulated directly by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) under two sections, either in relation to usage or storage at explosives-containing facilities (aluminum, AN, and chlorates)103 or when defined as Highly Hazardous Chemicals.104 These regulations focus primarily on the safety of the workers handling the materials, with only some storage requirements potentially impacting precursor chemical security, albeit indirectly.

Regardless of specific inclusion and contingencies, commercial nodes that handle precursor chemicals will be subject to OSHA’s general workplace regulations. For example, most businesses are required to have emergency action plans (EAPs), which include contingencies for events such as a fire.105 These EAPs require components, such as employee training, monitoring and alarm equipment, and evacuation plans. In some cases, close cooperation with local responders is required to maintain public safety. Because such regulations apply generally throughout the supply chain, individual supply chains (see Appendix D) only show symbols for those chemicals that are specifically considered highly hazardous by OSHA, as regulations are directly contingent on the presence of one of those precursor chemicals.

Mine Safety and Health Administration

For the purposes of this study, oversight by the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) only applies at end-user nodes that represent blasters that use commercial AN-based explosives where the precursor chemicals exist onsite in a neat, pre-mixed state. MSHA and ATF maintain an interagency memorandum of understanding regarding the enforcement of explosives regulations under such circumstances.106 Given the limited scope of these regulations for the purposes of this report, MSHA is grouped implicitly with OSHA on the relevant charts.

Department of Transportation

DOT’s primary interest with precursor chemicals is transportation safety, and it regulates all Group A chemicals except CAN (exempted under Special Provision 150) and UAN solution.107,108 The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) is responsible for regulating and ensuring the safe and secure movement of hazardous materials in commerce by all modes of transportation. The Office of Hazardous Materials Safety within PHMSA develops regulations and standards for the classifying, handling, and packaging of hazardous materials.109 A system of placards and labeling of packages and a shipping paper—that is, a manifest—that contains the material’s proper shipping name, class, division, United Nations identification number, and quantity as well as the number of packages, an emergency contact, and any special permits

to which transportation is subject must accompany each shipment. Thus, the identification of hazardous materials cargo is readily available to enable first responders to address incidents during transport. During transport, drivers must adhere to approved routes (dictated by state and local governments) and cannot leave vehicles unattended, both contingencies providing a security benefit.110 Security training is also required for those defined by regulation as hazardous materials employees. Both shippers and carriers of hazardous materials must obtain a Hazardous Materials Registration issued by PHMSA to perform their specific transportation functions.

Of the 520,000 truck carriers registered with the Federal Motor Carriers Safety Administration, 90,000 are authorized to transport hazardous materials.110 Carriers of hazardous materials are required to maintain certain minimum levels of financial responsibility for the cargo they transport in commerce; for example, interstate commerce transporters of oxidizers such as AN are required to maintain a minimum of $1,000,000 of coverage compared to a minimum of $5,000,000 for any quantity of Class 1, 2, and 3 explosive materials transported in interstate commerce, which also requires security plans for any quantity transported and routing plans for transporting quantities in excess of 55 lb.111,112 Some carriers are required to have a security plan for the transportation of a subclass of hazardous materials—including AN, hydrogen peroxide, nitric acid, and nitromethane—if they meet the specified threshold quantities.113 Security plans may include requirements for transfers and attendance by personnel, depending on transportation method.114

Department of Commerce

The Department of Commerce’s (DOC’s) Harmonized Tariff Schedule lists all the prioritized precursors (in Chapters 28, 29, 31, 76, 79, and 81) and dictates the duty rates for each material’s import.115 DOC also lists certain chemicals as export restricted, Category 1 on the Commerce Control List.116,117 In the cases of aluminum (1C111a.1) and magnesium (1C111a.2.a.3) powders, inclusion on the list depends on the average particle diameter of the material, for reasons of controlling missile technology, nuclear nonproliferation, regional stability, and antiterrorism. Equipment that produces aluminum powder is also restricted under 1B102c for missile technology and antiterrorism purposes. Magnalium (aluminum-magnesium alloy) powder is controlled under 1C1002c.1.d for nuclear nonproliferation, national security, and antiterrorism. AN formulations are controlled if meeting the definition under 1C997 (citing antiterrorism and regional stability) of containing “more than 15% by weight ammonium nitrate, except liquid fertilizers,” which, while covering both AN and CAN, excludes UAN solution. A license is required for AN with respect to export or re-export to Iraq. Nitric acid is listed under 1C999e if greater than 20% for antiterrorism and regional stability purposes, with licenses required for North Korea and Iraq.

State and Local Regulations

In addition to federal oversight, the commercial movement of precursor chemicals may be subject to state and local laws or ordinances depending on the specific jurisdiction. These may be independent or in excess of existing federal regulations, or they may be close mimics. An example of the latter is that most states have incorporated DOT regulations on hazardous materials transport into their statutes. There are thousands of statutory jurisdictions within the United States, and the committee could not review all of their policies on precursor chemicals; however, at the state level, some existing regulations pertaining to AN provide an illustrative example of nonfederal controls.

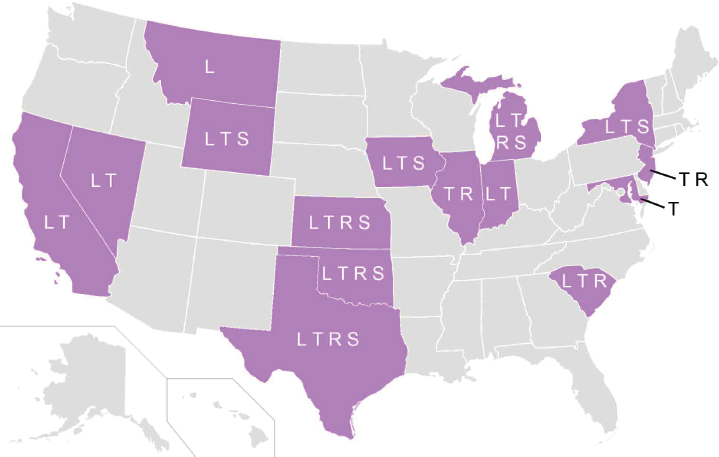

In anticipation of DHS’s AN rulemaking in 2008, several states implemented their own regulatory schemes that contain some common features (see Figure 3-3).58,118-133 Of the fifteen states with such schemes, the most prevalent point of commonality is record keeping on retail-level AN transactions; these records typically contain the date, information on the identity of the purchaser, and the quantity sold. Eleven of the fifteen states with regulatory schemes also require that the retailer maintain a license to sell the material, but a buyer does not require a license to purchase it. Roughly half of the states also require storage

NOTE: Indiana, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, and South Carolina do not regulate AN specifically, but cover it under general regulations dealing with fertilizers.

security for AN and specifically allow retailers to refuse sales to people behaving suspiciously. The committee heard from a representative of the New York Department of Agriculture, who provided further details of enforcement, which includes liaising with law enforcement during inspections to help promote compliance. The representative noted that the number of outlets carrying AN in New York declined after the state introduced the regulation and discussed legal opportunities for farmers to obtain restricted chemicals from out-of-state and out-of-country distributors that might not apply similar protections.

In general, state and local provisions may apply at any node within a precursor chemical’s supply chain, for example, through business permits, transportation route planning, or fire codes. Thus, given the thousands of political subdivisions in the United States and the committee’s task not allowing for a complete analysis of all possible controls, these marks are generally excluded from the supply chain charts in Appendix D, but are assumed to be possible at all stages to some degree in some places. Only the state laws affecting AN are included in the overlays in Figure 3-2 and Figures D-1 through D-11.

The state AN laws illustrate some of the challenges of controlling access to precursor chemicals at the subnational level. With respect to coverage, even if a state has controls, malicious actors can easily cross state lines and obtain the material where it is not regulated; all the AN-controlling states have at least one such border. A second issue is the lack of harmonization between the states. When given the option, each state will implement controls differently, so while common themes can be found throughout Figure 3-3, the lack of a unified control scheme can engender confusion and adds additional burdens to commerce while creating situations where nonmalicious actors unwittingly violate the law.134

Private-Public Partnerships

For this study, private-public partnerships are defined as programs wherein the government engages with private entities on a voluntary basis, with the goal of providing additional benefits without statutory changes.135 This can include programs that are directly managed by the government or those where statutory requirements may be accomplished by references to the literature produced by private entities.

Known Shipper Program

The Known Shipper Program (KSP) is a voluntary program originally created by the Federal Aviation Administration for strengthening air cargo security. The program establishes procedures for differentiating between shippers that are known and unknown for air carriers and indirect air carriers who tender cargo for air transportation.136,137 A known shipper is a person who has an established business relationship with an indirect air carrier or operator based on records

or other vetting. Currently, TSA allows using manual procedures, the Known Shipper Database, and the Known Shipper Management System to classify a shipper.

Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism

The Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (C-TPAT) is a voluntary private-public partnership authorized by the Security and Accountability for Every Port Act of 2006 with the goal of improving commercial security.138,139 C-TPAT partners work with CBP to develop security plans that protect their supply chains both from the introduction of contraband and from theft. In exchange, CBP allows for reduced inspections at the port of arrival, expedited processing at the border, and penalty mitigation. Compliance with the program is not free to shippers, and there are attendant costs.139

National Fire Protection Association

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) codes consolidate fundamental safeguards for the storage, use, and handling of hazardous materials in all occupancies and facilities (not necessarily with respect to security concerns), and are required by some levels of government and commercial operations. The codes do not apply to the storage or use of hazardous materials for individual use or residences. Relevant codes may include 400, Hazardous Materials (e.g., AN) or 484, Standard for Combustible Metals (e.g., aluminum powder). Due to the ubiquity of the NFPA codes and their adoption by myriad organizations, they are not shown on the supply chain charts.

Trade Associations Programs

Some trade associations condition membership on businesses’ participation in additional safety and security programs. Secure handling improvements might be accomplished through technical measures that address safety or security, incentives related to employment and human resources, and social or behavioral pressures. Specifically, programs may set specific secure handling goals; promote awareness and process change; publicly recognize firm participation; and promote organizations that implement secure handling practices. The programs listed in the following sections are not exhaustive of all the efforts of trade associations that work with the precursor chemicals, but provide illustrative examples.

The reach of these programs has limitations. Even if trade associations condition membership on participation, not all businesses in a particular industry choose to join a trade association. The representatives of one trade association that provided data to the committee acknowledged that not all businesses opt for membership, despite the benefits that membership conveys. Thus, even if all

members of a trade association participate in and comply with the association’s program, vulnerabilities might remain.

Institute of Makers of Explosives

The Institute of Makers of Explosives (IME) provides members with best practice training materials via its Safety Library Publications and via a risk assessment tool (IME Safety Analysis for Risk) used to calculate risk to personnel from commercial explosives manufacturing and storage facilities and operations. The members of this trade association primarily deal with bulk precursors (e.g., unbagged AN), only work with companies possessing ATF licenses, and follow the specified safety guidelines published by the trade association. Compliance with these procedures is required for membership, and the trade association represents greater than 90 percent of the industry.140 Publications relevant to this study include guides on AN and general transportation and storage.141-143 The latter guides include, but are not limited to, controlled access to manufacturing locations, storage areas, and transportation containers through locks and seals.

International Air Transport Association

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) works closely with governments and the International Civil Aviation Organization and member airlines to develop regulations that advance safety and facilitate fast and efficient transport of dangerous goods by air.144 The goal is to ensure that the regulations on dangerous goods transport are effective, efficient, and globally aligned. The IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations manual is a global reference for preparing, shipping, and transporting dangerous goods by air for the world’s airlines. Participation in this group would mostly affect the small quantities of precursors shipped by air via parcel carriers.

American Chemistry Council

The American Chemistry Council’s (ACC’s) Responsible Care program has the stated goal of increasing the industrial performance of its members with regard to security and safety.145,146 Areas of focus for security include site, supply chain, and cyber aspects. Participation in the program is a requirement of joining ACC and requires both performance reporting and third-party verification. The performance of specific companies is reported publicly to incentivize compliance (for a further discussion of voluntary compliance incentives, see Chapter 5). Similarly branded efforts have been used to build programs outside of the United States. It was reported that Responsible Care has significantly reduced health and safety incidents (53–78 percent depending on the measure) in member companies.

Society of Chemical Manufacturers and Affiliates

The Society of Chemical Manufacturers and Affiliates’ (SOCMA’s) ChemStewards, similar to Responsible Care, is focused on improving the health and safety practices of member companies.147 Participation is a requirement for SOCMA members who manufacture and handle synthetic and organic chemicals. Training and verification are concomitant with the program.

National Association of Chemical Distributors

The National Association of Chemical Distributors’ (NACD’s) Responsible Distribution is a safety and security program using third-party verification of compliance.148,149 Participation in the Responsible Distribution program is required for all members of the trade group, the bulk of which are small-scale distributor operations who may also break bulk shipments into smaller aliquots. Participation encompasses 250 distributors with a combined 1,900 facilities in the United States.

ResponsibleAg Inc.

ResponsibleAg Inc. is a nonprofit organization founded in 2014 to assist agribusinesses in complying with federal regulations regarding the safe handling and storage of fertilizer products.58,150,151 The organization provides participating businesses with a compliance audit relating to the safe storage and handling of fertilizers, recommendations for corrective action where needed, and resources to assist in this regard. Program-credentialed, third-party auditors use an internal checklist to ascertain compliance every 3 years, and if the auditor identifies issues, the facility will receive a corrective action plan with recommendations; a facility is not certified until all issues are addressed. As of December 2016, 2,282 facilities have participated in the program, with 452 reaching full compliance.150

Outreach

Unlike the trade association–sponsored programs in the preceding section, those listed below are neither required for membership in any organization nor required by statute, and therefore might cover less of the relevant industries. Outreach efforts include both industry-led and government-sponsored activities, and may also include outreach from the federal government to state and local emergency responders.152

Government activities presented to the committee include efforts by ATF153 and FBI154 to increase awareness and reporting of suspicious activity. ATF has focused on educating and developing relationships with the fertilizer industry to limit illegitimate access to precursor chemicals such as AN by increasing voluntary reporting of suspicious activity involving the precursors and increasing

awareness of security vulnerabilities. The program initiatives include Be Aware for America, Be Secure for America, and America’s Security Begins with You. FBI has engaged in efforts targeting retailers (e.g., pool and spa and beautician suppliers carrying hydrogen peroxide). FBI reported that consistent results require ongoing outreach because of the high turnover rate of retailers.

Outreach in the form of sharing threat information with industry so that they can take appropriate precautions has also been reported. DHS has in the past provided information on federally sponsored training and education resources in which industry may partake.155

Best Practices

Best practices for security can make it harder to misappropriate precursor chemicals, and in this report are defined as those activities that are undertaken by an independent entity and are not part of any other mandatory or voluntary requirements. Best practices may include, but are not limited to, protection of assets by authentication, alarms, physical barriers, and facility personnel.156 Some private industries also implement more stringent customer vetting to increase security, which may include background checks, inspections of receiving facilities, or global positioning system (GPS) tracking of shipments. There is also a set of publicly available literature on security practices, authored by both government157,158 and private groups,159 that offers more details for anyone who is interested in implementing best practices absent a more formal structure.

SUPPLY CHAIN VULNERABILITIES

If locks keep honest people honest by preventing unauthorized entry, then it could be said that laws, regulations, and voluntary measures will help ensure that honest, conscientious manufacturers, purveyors, and consumers of precursor chemicals oversee Group A chemicals adequately. However, the unexplained loss, diversion, or theft of precursor chemicals and the potential unintended consequences to the commercial enterprises that make or sell them cannot be taken lightly. The purpose of this section is to highlight potential areas of vulnerability in supply chains that handle precursor chemicals. The policy coverage shown in Figure 3-2 suggests that the potential for a malicious actor to acquire a precursor chemical increases toward the end of the supply chain.

Types of Vulnerabilities

Laws, regulations, and voluntary measures are in place primarily to ensure that precursor chemicals remain under the direction of legitimate possessors who handle and use the materials. The primary security concerns in the chemical supply chains are potential vulnerabilities to unexplained loss, diversion, and theft, any of which could lead to malicious actors having access to potentially danger-

ous materials. Additionally, given the widespread availability of the precursors at retail nodes, there is an opportunity for legal acquisition for illegitimate applications (e.g., by misusing exploding targets kits, described below).

Unexplained Loss

An unexplained loss, for the purpose of this report, is an amount of precursor chemical that disappears from the supply chain without knowledge of the cause. The cyclic counting of stock in inventory with a reconciliation of acquisitions and distributions is a method used to determine evidence of losses. Losses of certain hazardous materials that are precursor chemicals are not generally reportable to authorities unless there are state regulations requiring these actions or the precursor chemicals are CFATS chemicals of interest stored at CFATS-regulated chemical facilities that have approved security plans.

Unexplained losses may or may not signal a threat to security. If a precursor chemical is misplaced or lost due to inaccurate inventory record keeping, it may eventually turn up. Unexplained losses that remain unresolved should potentially be considered to be in the hands of malicious actors and therefore to pose a threat.

Diversion

Diversion, as defined by Stanton,160 is “a form of misappropriation. It is an act of acquiring a product by means of deception. The types of deception vary and do not always include the failure to compensate the targeted company. In all cases of diversion, the common factor is that the targeted company causes the diverted chemical to be placed into transportation. Preventing diversion starts with knowing your customer.” At regulated nodes of the supply chain, diversion would likely require a recognized or authorized buyer of a particular chemical to act as an intermediary for an unintended recipient. This action might jeopardize the legitimate buyer’s credentials, if it needed credentials for the transaction and a regulatory agency recognized that diversion had occurred.

Theft

Theft, for the purposes of this report, is the misappropriation of precursor chemicals without permission or payment where the material is presumed stolen and missing. Theft may be internally reportable within a commercial enterprise, but may not be reportable—or reported—to any local, state, or federal law enforcement agency. A single large-scale theft of a precursor chemical might be difficult to execute because it would be noticed easily and raise alarms. Theft of small quantities of precursor chemicals—in one event or stretched over time—may not be detectable and could be mislabeled as losses.

Coverage of Controls and Other Policy Mechanisms

Importers, manufacturers, and remanufacturers tend to fall under greater scrutiny due to existing oversight, such as DHS’s CFATS (see Figure 3-2 and Appendix D), that requires significant documentation and inspection of on-hand quantities of precursor chemicals. With some exceptions, namely industrial end users and agricultural retailers, visibility and oversight of precursor chemicals appear to decline as precursor chemicals make their way through the supply chain. Because of this, the potential for misappropriation becomes more apparent at the later stages in the supply chain.

It is conceivable that the physical transfer of chemicals from one entity to another, for example, involving transportation or temporary storage nodes, represents an opportunity for thieves to gain direct access to the chemicals. Safeguards are generally in place in the transportation modes through verification of receiving weights or weigh station records, but they may not prevent malicious actors from extracting small quantities of chemicals. Although distributors, wholesalers, and retailers are cognizant of the threat of internal theft in warehouses and distribution centers,161 as well as in retail outlets open to the public, the quantities of missing material might be small enough to avoid concern or suspicion.

A brief inspection of Figure 3-2 suggests that there are few controls or other policy mechanisms in place at retail outlets, apart from those in the agricultural sector. Parcel carriers also lack coverage, but might benefit from substantial, inherent traceability.

Of particular note, the committee found a pronounced lack of visibility and oversight in retail-level, nonagricultural transactions, especially those involving e-commerce, suggesting ample opportunity for malicious actors to acquire precursor chemicals for making HMEs. In many cases, consumers can legally purchase or acquire precursor chemicals, either in raw form or as components of other products, for legitimate commercial and noncommercial purposes. Hobbyists who manufacture amateur pyrotechnics for personal use might work with aluminum powder and potassium chlorate to create a display, and individuals who operate radio-controlled aircraft or cars might use nitromethane as fuel. Apart from its agricultural uses, AN is also an ingredient in some widely available household products. Many cold packs that are commonly sold in grocery and drug stores for use in first aid contain AN, as do exploding target kits used by archers and sporting firearms enthusiasts (see below). In the case of cold packs, it would not be difficult to remove the active chemical and put it to a different use.

The legal, retail acquisition of precursor chemicals for nonagricultural purposes might often occur in small quantities, either in person or online, but determined malicious actors could conceivably acquire a significant amount of material in a relatively short period of time. They might, for example, make multiple purchases, across multiple outlets, using cash or other nonidentifying purchase arrangements to avoid identification.

Moreover, as the Oklahoma City and Oslo bombings have demonstrated,23,24 malicious actors can also pose as commercial entities to purchase large quantities of precursor chemicals without verification. In the United States, subnational restrictions and voluntary programs, such as Responsible Ag, have emerged over time that might reduce the risks of similar actions today in many domestic jurisdictions, but there are no federal controls in place that require retailers to ask for identification, reason for purchase, or other means of verification.

EXPLODING TARGETS

While every precursor chemical in Groups A, B, and C can be legally acquired by noncommercial users as both neat and finished products (see Appendix D), not all of the formulations pose the same threat of misuse for making HMEs. Commercially available binary exploding target (ET) kits provide an easy route of precursor chemical acquisition in the United States. Typically, the ET kit will have either AN or potassium perchlorate as the oxidizer and powdered aluminum as the fuel, all three of which are Group A chemicals. The kit’s components are not explosive materials until mixed.

At the time of this report, most commercially available ET kits use AN—likely given its easier and safer handling—while potassium perchlorate is used in specialty ETs that require heightened sensitivity, to be initiated by less-energetic rounds. The capabilities of ETs are well described and readily apparent on the internet, which has given them high visibility to anyone searching for ways to produce IEDs. States and federal law enforcement agencies, such as FBI, have expressed concerns over the potential use of ETs in IEDs.162 Because the AN-containing kits are a common, complete finished product available to the general public—and because they have been implicated as components in recent, high-profile attacks in New York and New Jersey (Table 2-1)—their properties are detailed below.

Chemical Characteristics

The danger of ET kits is of greater concern relative to other precursor sources because the precursor chemicals contained in them have been designed to produce a high explosive that is both detonable and requires minimized amounts of energy to be initiated. Additionally, unlike other products containing chemical precursors, no technical knowledge or expertise in chemistry is required to use the kits to produce an HME—indeed, they are packaged with instructions on how to use the components to make an HME—thus removing any barrier of use for would-be malicious actors. While the kits are highly accessible, people can and do construct their own ETs from other precursor sources.

Form

The two components, AN and aluminum, exist in a variety of forms, with different porosities and particle sizes used in different applications. Particles with higher surface area to volume ratios maximize contact between the fuel and oxidizer and increase the rate of reaction, and thus the explosive power. By including the two components in the optimal physical form for making an explosive, ET kits remove the need for malicious actors to process or refine the precursor chemicals to make a usable HME.

Weight Ratio

To make the most easily initiated binary explosive, the oxidizer and fuel components must be the proper particle sizes and be mixed in the proper proportions to ensure detonation (see the Detonability section below). In ET kits, each component is packed in the precise physical form and ratios so that when mixed the optimum conditions are created to ensure easy initiation of the HME from the impact of a bullet.

Detonability

Many HMEs require a detonator to initiate the charge. Many AN mixtures in particular require not only a detonator, but also contact with a larger mass of explosive set off by the detonator to ensure that the HME functions. ETs do not require a detonator as they are sensitive to lower shock inputs (e.g., a bullet impact). This property lowers the difficulty of deploying ETs in IEDs.

Legal Considerations

Federal and state regulations that control AN and aluminum also apply to ET kits, provided the packaged precursor chemicals meet the thresholds stated in the regulations. Even when these regulations do not control the ET kits or their components, however, federal and state entities may issue guidance on ET kit acquisition and use because of the potential for their misuse to make HMEs for IEDs.

Federal

The federal government does not directly regulate the sale or use of ETs, except for the U.S. Forest Service, which bans their use on federal land in the Rocky Mountain region to prevent forest fires.163 While ATF and DHS regulate the commerce and security of explosives and precursor chemicals, respectively, as described previously, neither has the mandate or authority to regulate ETs.

ATF does not regulate the distribution and sale of ET kits because the individual components, when unmixed, do not meet the definition of explosive

materials that establishes ATF’s regulatory jurisdiction.164,165 An ATF manufacturing license is not required by the consumer to mix the components because mixing falls under personal use. Transportation and storage requirements do apply once the components are mixed.

DHS oversees precursor chemicals for security reasons. However, unless the quantity of ETs located at a particular facility brings the total weight of AN or aluminum within CFATS thresholds (2,000 and 100 lb, respectively), those locations are not subject to DHS oversight. Additionally, if those thresholds were met, DHS would only regulate the security at the location, not transactions.

Similar to the outreach efforts by ATF to agricultural retailers and by FBI to other retailers, FBI has released a private-sector advisory for retailers that carry ET kits. This advisory describes different types of suspicious behavior, describes steps that retailers can take if they believe a transaction is suspicious, and provides a phone number for reporting that activity. Some ET kit manufacturers include FBI advisory, relevant ATF statutes, and prohibitions of use on certain federal lands on their websites. They also include instructions for persons to check for compliance with state and local laws.166

State

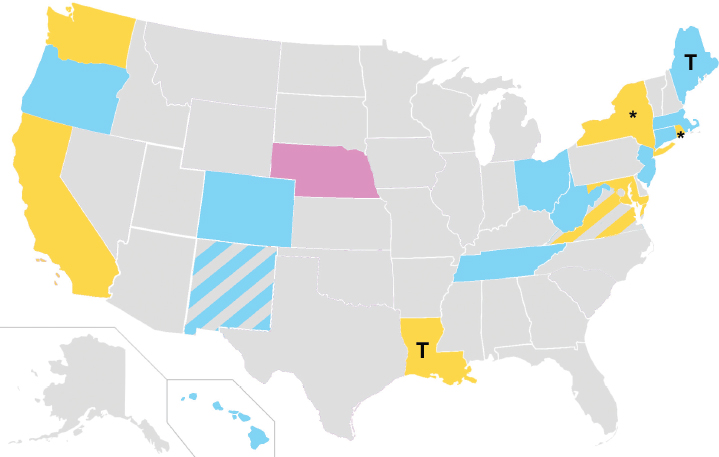

In lieu of federal controls, a number of states address ET kits at the retail or consumer level of the supply chain. As in the case of state regulations that control AN (see Figure 3-3), the regulations vary by state (see Figure 3-4).

Two states have laws under consideration that would directly address ETs: Rhode Island167 would ban ETs outright, whereas New York168 would require a valid permit for purchase.

Five states currently regulate the purchase of ET kits via licensing or permitting, either explicitly or implicitly. Washington169 requires a license and California170 requires a permit to lawfully possess the components with the intent to combine them to form an HME. Massachusetts similarly bans the possession of materials that can be combined to make a “destructive device” without “lawful authority.”171 Maryland172 and Louisiana173 have instead approached the issue by redefining the term “explosives” in their relevant statutes explicitly to include two or more nonexplosive materials that are sold together and that when mixed become explosive. There is some ambiguity in Virginia due to their explosives statute, where the interpretation of the exemption for “lawful purpose” may or may not include ETs.174 The Attorney General of Virginia issued an opinion in 2014 on the issue, stating that possessing and using ETs for their designated purpose (i.e., recreational use) is legal.175

Ten states regulate ETs under statutes that require a license to manufacture and possess explosives.176-185 In these states, purchasing the ET kit is legal, but mixing the components is illegal without a license. In New Mexico, the manufacture and possession of ET kits for “legitimate and lawful . . . sporting purposes”

is lawful, depending on the interpretation of the statute.177 To the committee’s knowledge, authorities in at least four states—Ohio (State Fire Marshal),186 Tennessee (Attorney General),187 Connecticut (Office of Legislative Research),188 and Massachusetts (State Fire Marshal)189—have rendered the opinion that, when mixed, exploding targets are subject to existing statutes on explosives. Tennessee requires a license to manufacture explosives but does not issue such licenses, thus effectively banning the mixing and use, but not the purchase, of ET kits within the state.

Nebraska falls into its own regulatory category because it only regulates the use of explosives, not the possession of them or their components.190 Thus, it is legal to purchase ET kits and mix the components, but detonating the ET requires a permit.

Two states provide the additional caveat that the possession and use of less than or equal to 5 lb of unmixed (Louisiana173) or mixed (Maine185) ET products does not require a license.

CONCLUSION

This chapter highlights the reduced visibility and oversight as precursor chemicals flow through the supply chain and approach consumers. Often, this decreasing oversight is driven by the amount, weight, or volume of materials on hand at a given node. As illustrated in Table 3-1, many chemicals have thresholds (quantities and/or concentrations) below which oversight and inspections are no longer required. Businesses might maintain precursor chemicals below the threshold to avoid regulation, as with the example cited previously of industry reducing the concentration of hydrogen peroxide in products to fall below the CFATS threshold of 35%.55 Generally, the longer the supply chain and the smaller the deliverable quantity, the less visibility there is of the material.

For most of the precursor chemicals, the total number of entities and affected parties for each type of node greatly proliferates as the precursor chemicals move down the supply chain. Returning to the AN example, only six domestic plants manufacture AN, but thousands of agricultural retailers and farmers use the material, and even more nonagricultural entities or individuals use AN-containing products. In this respect, the opportunities for misappropriation of precursor chemicals increase with increasing distance from the point of origin in the supply chain. Moreover, enterprises that depend on their trade in chemicals and need their licenses or permits to stay in business might be more aware of risks and take greater precautions to secure facilities, guard inventories, maintain records, obey regulations, and conform to agency oversight requests than those dealing with smaller quantities that represent a small fraction of their primary business.

Regulation and oversight decline as quantities or concentrations fall below thresholds; however, sufficient small quantities can be amassed to cause concern. These small quantities can be obtained illegally or legally, but are all available legally.

The committee speculates that the likelihood of unexplained loss, diversion, or theft is inversely proportional to the amount of material being sold or stored. In other words, the smaller the quantity of product that changes hands, the less likely it is that a control or other policy mechanism governs the transfer, making it easier to misappropriate. Because there is little federal, state, or local oversight of small-scale transactions, the most likely point of illegitimate acquisition of precursor chemicals is at retail-level nodes, especially nonagricultural or noncommercial (Figure 3-5).

Regarding legitimate sales, purchasing small amounts of many of the precursor chemicals can go unnoticed because there is no requirement to track or log the sale and no assurance of a payment trail. While larger transfers of material might trigger an electronic record, small cash-like exchanges might remain anonymous. Consumers can obtain all Group A precursor chemicals online from multiple sources, and enforcing current, voluntary restrictions on internet sales presents challenges. Moreover, the European Union, discussed in the next chapter, suggests that mandatory restrictions on e-commerce can also present challenges.191

TABLE 3-1 Summary of Controls and Thresholds

| ATF | CFATS | EPA | USCG | OSHA | DOT | DOC | DEA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Aluminum Powder | 100 | XT | XB | X‡ | I, EX (<200 μm) | |||

| Ammonium Nitrate | 2,000 (≥33%) | XD,T | XB | X† | I, EX (≥15%) | ||||

| CAN | XD,T | I, EX (≥15%AN) | |||||||

| Hydrogen Peroxide | 400 (≥35%) | 1,000T (>52%) | 7,500 (≥52%) | X† (≥8%) | I | ||||

| Nitric Acid | 400 (≥68%) | 1,000T | X (<70%) | 500 (≥94.5%) | X† | I, EX (≥20%) | |||

| Nitromethane | 400 | XT | 2,500 | X† | I | ||||

| Potassium Chlorate | 400 | XB | X† | I | |||||

| Potassium Perchlorate | 400 | X† | I | ||||||

| Sodium Chlorate | 400 | X (<50%a) | XB | X† | I | ||||

| UAN Solution | XD | X | I | ||||||

| Group B | Calcium Nitrate | XD,T | X (NCF) | I | |||||

| Hydrochloric Acid | 15,000 (≥37%) | 5,000T (≥37%) | X | 5,000 (0%W) | X | I | X | ||

| Potassium Nitrate | 400 | XD,T | X | I | |||||

| Potassium Permanganate | 400 | 100T | X† | I | X |

| Group B | Sodium Nitrate | 400 | XD,T | X | I | ||||

| Sodium Nitrite | 100T | X | I | ||||||

| Sulfur | XT | X (M) | X (M,P) | I | |||||

| Sulfuric Acid | 1,000 | X | 1,000 (65-80%) | X† | I | X | |||

| Urea | XT | I | |||||||

| Zinc Powder | 1,000T | X‡ | I | ||||||

| Group C | Ammonium Perchlorate | X (<15 μm) | 400 | XT | 7,500 | X† | I | ||

| Antimony Trisulfide | XT | X† (>0.5%As) | I | ||||||

| Hexamine | XT | I | |||||||

| Magnalium Powder | X‡ | I, EX | |||||||

| Magnesium Powder | 100 | XT | X‡ | I, EX (<60 μm) | X | ||||

| Pentaerythritol | I | ||||||||

| Phenol | 500/1,000T | X | X† | I | |||||

| Potassium Nitrite | X† | I |

NOTE: A: aqueous; B: only when stored at a blasting location (under 1910.109); D: only when in an aqueous solution (under N511); EX: export restricted with caveats in parentheses; I: listed on the Harmonized Tariff Schedule; M: molten; NCF: not certain fertilizers; P: powder; PPF: powder, paste, and flake; T: TSCA threshold of 25,000 lb/yr; W: water; X: listed without threshold mass. A DOT security plan is required if transported in excess of 3,000 kg or L (†), or if other conditions are met (‡), but does not apply to 4.2 aluminum powder, <20% nitric acid, non-fuming sulfuric acid, or farmers.